Given a minute or two, I suspect most could recount instances of the news reporting on riots and widescale violent protests. Indeed, in the past few years, the frequency of such events seems to have increased. Think of the outrage (both immediate and continued) after George Floyd’s or Breonna Taylor’s murders by police, or the riots in France over the shooting of Nahel M., also by the police. In 2019, during the 70th anniversary of the founding of the People’s Republic of China, Hongkongers protested violently against the mainland’s increasingly oppressive control. And who could forget the 2021 January 6th insurrection, where supporters of Donald Trump, spurred on by the former president himself, invaded the U.S. Capitol Building, resulting in the deaths of at least seven people. No matter where one turns, violence, rather than discourse, is increasingly the avenue through which we reconcile our disagreements and address profound injustices (be those actual or imagined).

This is not to say that it is actually the case that we’re protesting and rioting more. Simply that the news and other media appear to feature such events more often than they once had.

Violence, however, is typically seen as antithetical to the liberal democratic process so often associated with developed nations. In such nation-states, we’re not meant to solve our problems with force and intimidation but with words and impassioned speeches. If one wants to change the political system or draw attention to a systematic injustice, we’re not meant to smash up shops and set fire to cars but call upon our elected officials to enact changes or go to the media so they can spotlight wrongdoing. As Mónica Soares and others argue, violent protest simply does not have a place in the democratic process. But is this right? Are we always wrong to act violently against the state?

Well, a violence-free political system certainly sounds appealing. After all, at the heart of liberal democracy is not only the recognition that we will disagree with each other, but that we should. Through careful, structured, rigorous debate and discussion, we are meant to exorcise our demons so that we might better understand the issues at play and, crucially, what actions individuals, organizations, and society must take to address problems. You see this when elected officials argue in their respective chambers, be that the U.K.’s House of Commons, the U.S. Senate floor, or Mexico’s Chamber of Deputies. When people disagree, discussion and reason – not violence – are meant to provide an avenue to insight and compromise. In short, we should resolve our conflicts in the marketplace of ideas and not in the brutish state of nature.

And in a perfect world, this would be the case; political violence would be unheard of because it would be unnecessary. Unfortunately, we don’t live in a perfect world, and regardless of where one resides, political coercion and injustice are always on the cards.

Even in countries which claim to be paragons of liberal and democratic principles, wrongs occur. And not just any injustice but those committed by state actors acting on behalf of the state against citizens and non-citizens alike. From police shootings to financial mismanagement, and draconian laws limiting free speech to surveillance initiatives, the state is always trying to increase its powers, often in the language of protecting its citizens and their interests.

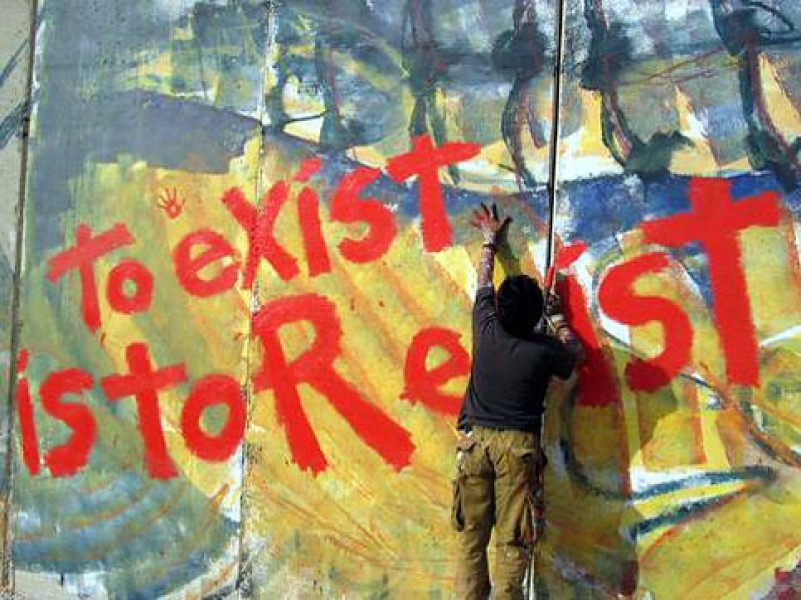

So, what are we to do when the state, with all its power and legitimacy, oversteps the mark? What should you do as a citizen of your nation when those in power refuse to listen to what you have to say or act against your interests? What happens when the state excludes you from the marketplace of ideas?

According to James Greenwood-Reeves, in his recent book Justifying Violent Protest, one answer – which can be rational and grounded in moral principles – is violent protest. It is not that such actions are antithetical to the liberal democratic project but are, under certain circumstances, entirely justified and even necessary. They are examples of extraordinary course corrections in the face of equally remarkable events.

States as they exist today are not eternal or innocuous things that just are. They have come into being off the back and forth between enemies and allies over multiple centuries. Most importantly, though, they require your obedience. Each state constrains the actions of those who reside within it. Typically, we see this as a good thing as other people’s actions are equally constrained, and these constraints allow you to live together. Without them, everyone would be free to do whatever they willed, and this would cause problems because people’s desires would conflict. So, the state needs you to play by its rules, but for this to be successful, it requires you to want to do so. Its coercive effect needs to be seen as justified in the very eyes of those it coerces. If it fails to do this, disobedience emerges, and this can be anything from minor infractions to violent revolution. As Greenwood-Reeves writes:

Poor moral arguments for obedience entail greater moral reason for disobedience. Violent protest can act, like any other form of protest, as democratic dialogue, addressing these perceived legitimacy deficits and presenting a form of moral argument – even when the use of violence seems spontaneous or opportunistic.

Sometimes we see, on the news, the overthrow of oppressive regimes in far-off places, and, for the most part, we consider this a good thing. When tyrants are expelled from the halls of power by those over whom they exercised their terrible control, we cheer for those who establish a better community for themselves and their fellow citizens. But, such revolutions, by their very nature, are violent. Illegitimate political systems and nefarious state actors never relinquish their power freely; it is always pried from their hands. Yet, the fact that such revolutions involve, to one degree or another, a level of violence doesn’t cause us to balk instantly. Instead, we acknowledge that violence can be a legitimate political tool when the state becomes illegitimate and can no longer justifiably demand obedience from its citizens.

How we draw this line between legitimate and illegitimate states is, however, difficult to agree on (and not something I could hope to tackle here). Nevertheless, one need not identify the precise line to be drawn to acknowledge that some distinction must exist. What is even more important to remember is that the downward spiral towards state overreach is always present. Regardless of how restrained a government might be or how morally just a state might act, the allure of increased control or illegitimate action is ever-present. When political systems start towards a path of control, regardless of how justified it may seem, violent protest can become a justified response.

Discourse and discussion should always be the first port of call when we disagree with each other and, crucially, with the state’s actions. Violence is not, and should not be, the first tool one reaches for when they disagree with the society in which they live. But this does not mean that violence is never the right course of action. When the state can no longer expect your obedience because its actions, philosophies, and laws contradict the moral foundations to which it lays claim, when it claims to be protecting freedoms while simultaneously eroding them to secure its powers, individual actors can be justified in transitioning from peaceful to violent protest.