The topic of testing on animals as a form of scientific research has been contentious for quite some time. In most cases, the discussion tends to focus on whether it is morally permissible to test various products and procedures on animals in order to determine whether they would be safe and beneficial for human use. Animal experimentation is not always conducted simply for the benefit of human beings—sometimes the parties that stand to benefit from the research are other non-human animals, often including other members of the same species as the animals being tested.

Defenders of the practice of testing on animals for the benefit of humans argue that the benefits for humans substantially outweigh the harms incurred by animals. Some argue that our moral obligations extend only to other members of the moral community. Among other things, members of the moral community can recognize the nature of rights and obligations and are capable of being motivated to act on the basis of moral reasons. Non-human animals, because they are not capable of these kinds of reflections, are not members of the moral community. As such, defenders of animals testing argue, they don’t have rights. In response, critics argue that if we only have obligations to beings that can recognize the nature of moral obligations, then we don’t have obligations to very young children or to permanently mentally disabled humans, and this idea is morally indefensible.

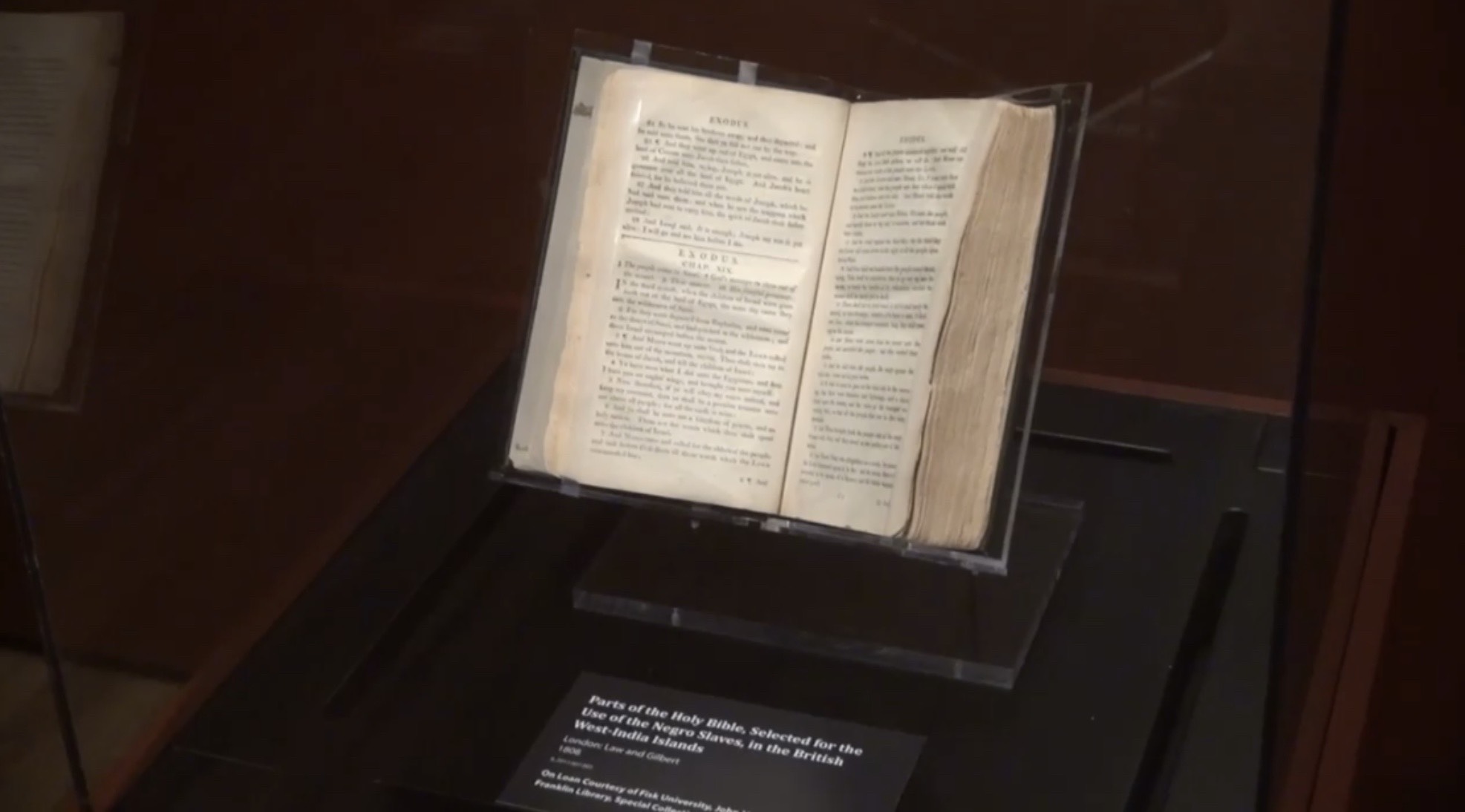

Other defenders of animal testing argue that it is both natural and proper for human beings to exercise dominion over animals. These arguments take more than one form. Some people who make this argument are motivated by passages from the Bible. Genesis 1:26 reads, “And God said, Let us make man in our image, after our likeness: and let them have dominion over the fish of the sea, and over the fowl of the air, and over the cattle, and over all the earth, and over every creeping thing that creepeth upon the earth.” Some argue that this passage suggests that humans have divine permission to use animals as they see fit. The use of animals for the benefit of humans seems morally defensible to these people for this reason.

Others argue human dominion over other animals is appropriate because human beings have demonstrated their superiority over non-human animals. We are no different from other animals in the sense that we use our natural skills to climb as high on the food chain as our circumstance permit. As rational creatures, our needs extend farther than the needs of non-human animals. As a result, we can use non-human animals to solve a wider range of problems. We can use them not only for protein, but to make our lives longer, better, more beautiful, and more convenient. Critics of such a view argue that might doesn’t make right. What’s more, our enhanced rational capacities also give us the ability to make moral judgments, and these moral judgments should extend to compassion for the suffering of all living creatures.

Arguments against research on animals also come in a variety of forms. One approach focuses on suffering. Famously, Peter Singer argued that what makes a being deserving of moral consideration is their capacity to suffer. If we treat equal amounts of suffering unequally simply because of the species to which the animal happens to belong, our behavior is speciesist—we are taking seriously considerations that are morally irrelevant. Rights based approaches, like the one argued by Tom Regan point out that non-human animals are subjects of lives. There is something it is like for them to experience the world in the unique way that they do. In light of this, we should recognize that non-human animals have intrinsic value and they should not be used as objects to be manipulated for the benefit of human beings.

How should we assess the situation when the research done on non-human animals is done, not for the benefit of human beings, but for the benefit of other non-human animals? In these cases, one major criticism of testing disappears—researchers can’t be accused of failing to take the interests of non-human animals seriously. After all, concern for the interests of non-human animals is what motivates this research to begin with. Vaccines for rabies, canine parvovirus, distemper, and feline leukemia virus have been developed through the use of animal research. These critical procedures improve and even save the lives of non-human animals. When we engage in a consequentialist assessment of the practice, testing on non-human animals for the benefit of other non-human animals seems justified.

On the other hand, it may be that speciesism is rearing its ugly head again in this case. Consider a parallel case in which research was being conducted for the good of human beings. Imagine that a tremendous amount of good could be done for human beings at large if we tested a particular product on a human being. The testing of this product would cause tremendous physical pain to the human being, and may even cause their death. Presumably, we would not think that it is justified to experiment on the human. The ends do not justify the means.

One might think that one major difference between the case of testing on humans and the case of testing on animals is that humans are capable of giving consent and animals are not. So, on this view, if we kidnap a human for the purposes of experimenting on her to achieve some greater good, what we have done wrong, is, in part, violating the autonomy of the individual. Animals aren’t capable of giving consent, so it is not possible to violate their autonomy in this way.

Under the microscope, this way of carving up the situation doesn’t track our ordinary discourse about consent. It is, of course, true, that humans are free to use freely (within limits) certain things that are incapable of giving consent. For example, humans can use grain and stone and so on without fear of violating any important moral principle. In other cases in which consent is not possible, we tend to have very different intuitions. Very young children, for example, aren’t capable of consent, and for that very reason we tend to think it is not morally permissible for us to use them as mere means to our own ends. Beings that are conscious but are incapable of giving consent seem worthy of special protection. So it seems wrong to test on them even if it is for the good of their own species. Is it speciesist to think that the ends can’t justify the means in the case of the unwilling human subject but not in the case of the unwilling non-human animal?

Testing on non-human animals for the sake of other non-human animals also raises other sets of unique moral concerns and questions. What is the proper rank ordering of moral obligations when the stakeholders are abstractions? Imagine that we are considering doing an experiment on Coco the chimpanzee. The experiment that we do on Coco might have implications for future chimpanzees with Coco’s condition. The research might, then, have a beneficial impact for Coco’s species—the species “chimpanzee.” Can the moral obligations that we have to concrete, suffering beings ever be outweighed by obligations that we have to abstractions like “future generations” or “survival of the species”?