US President Donald Trump has signed an executive order instructing the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) to review legislation that shields social media platforms, like Twitter and Facebook, from liability for content posted by their users. This move appears to be a retaliatory gesture against Twitter for linking fact-checking sites to President Trump’s tweets opining the vulnerability to fraud of mail-in ballots for upcoming elections. This is the second time President Trump has drafted an executive order to review this kind of legislation. The first time was in August 2019. But this isn’t simply (another) Trump temper tantrum. Rather it is the latest push in a concerted and bipartisan effort to bring so-called “Big Tech” companies to heel. These efforts in general face a long road of legal and philosophical challenges, and Trump’s effort in particular is likely doomed to failure.

The relevant legislation is the Telecommunications Act of 1996, and more specifically the “Good Samaritan” clause of Section 230 therein. This clause states that no “provider or user” of an “interactive computer service” can be sued for civil harm because of “good faith efforts” to restrict access to “objectionable” material posted by other users of their service. Other portions of Section 230 give providers and users of interactive computer services immunity against being sued for any civil harm caused by content posted by other users. Essentially, companies like Twitter, Facebook, and Google are given broad discretion to handle the content posted on their sites as they see fit.

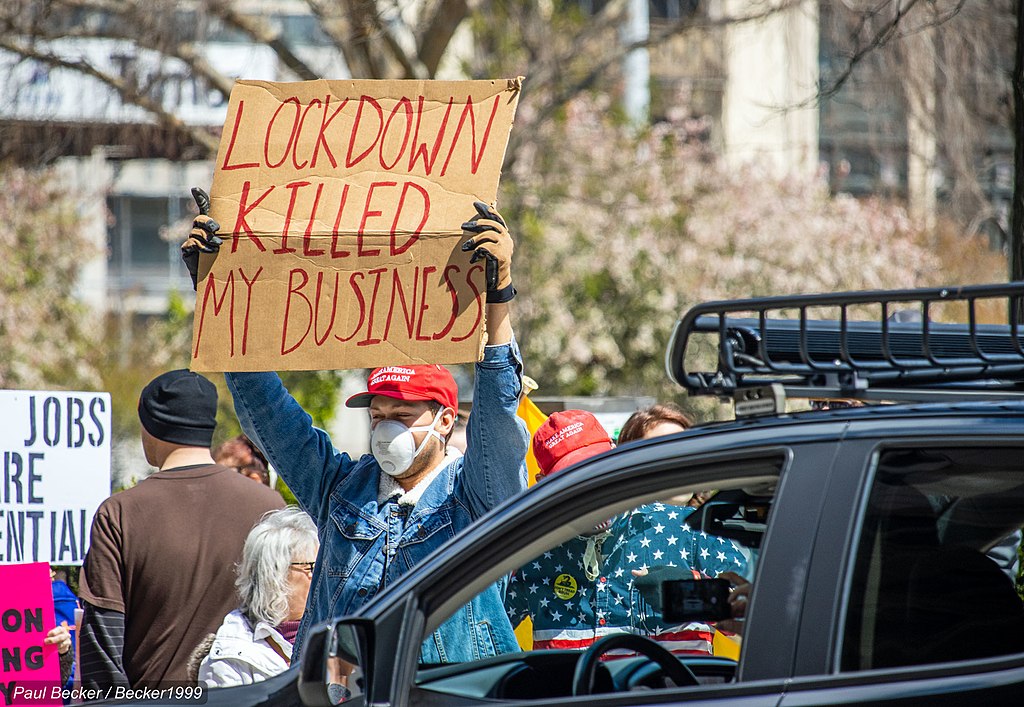

Republicans complain that Big Tech companies harbor anti-conservative political bias, which they enforce through their platforms’ outsized influence on the dissemination of news and opinion. Texas’ Senator Ted Cruz has argued that Facebook has censored and suppressed conservative expression on its platform. President Trump’s frequent screeds against CNN, The Washington Post, and Twitter echo the same sentiment. In 2018, Google CEO Sundar Pichai was grilled by Republican lawmakers about alleged anti-conservative bias in his company’s handling of search results. Missouri’s Senator Josh Hawley in 2019 introduced a bill to amend Section 230 to remove its broad protections from liability. Hawley’s bill was specifically geared toward addressing alleged anti-conservative bias and offered reinstatement of Section 230’s protection only to companies who submitted themselves to an audit showing that they pursued “politically neutral” practices.

Liberal and Democratic concerns focus largely on the spread of harmful misinformation and disinformation by foreign actors aimed at influencing US elections. But there are two points of bipartisan agreement. The first concerns the scope and magnitude of Big Tech’s influence on the public exchange of information. Agreement here manifests itself in the what criteria lawmakers have put forward as triggering expanded liability, namely size. Senator Josh Hawley’s 2019 bill targeted companies with, “30 million monthly active users in the US, more than 300 million active monthly users worldwide, or more than $500 million in global annual revenue.” The other is point of agreement concerns posted content related to human trafficking for sex work. Legislation amending the Telecommunications Act of 1996 pursuant to curtailing human trafficking was passed with bipartisan support in 2017.

All of this bears on the right to freedom of speech, interpretation of which is a perpetually contentious issue. Conservatives complaining about censorship and suppression allege that their freedom of speech is being infringed by the actions of Big Tech. However a recent judicial decision made short work of one such complaint. The US Court of Appeals dismissed a suit claiming that Twitter, Facebook, Apple, and Google had conspired to suppress conservative speech. In their ruling the judges noted that the First Amendment only protects free speech from interference by government action. This illustrates an important point about the nature of rights that is often missed.

Rights can be thought of as comprising three elements: a right-holder, an obligation, and an obliged party. With the right to freedom of speech the right-holder is any legal person (which includes corporations), the obligation is to refrain from suppression/censorship, and the obligated party is the US government. Constitutional rights tend to follow this pattern. Other rights oblige parties other than just the government. A family can sue someone for killing their mother, or the state may sue on the murder victim’s behalf, because a right to life is both understood to exist at common law and is also enshrined by legislation in statutes against homicide. Here the right holder is any individual person, the obligation is to refrain from killing the right-holder, and the obligated party is every other individual person. (Incidentally, both of these are examples of negative rights: rights which entitle the bearers to protection from specific harmful treatment. There are also positive rights, which entitle the bears to the provision of specific goods, services, or treatment.)

As a matter of principle there is no general legal basis for complaints against Big Tech for suppressing or censoring expression. They are not government actors and so are not obviously bound by the right to free speech as expressed in the first amendment. The US Court of Appeals decision mentioned above says as much. Further these companies are themselves legal persons with respect to political speech under US law. This was one the bases of the US Supreme Courts’ (in)famous Citizens United decision. Because corporations are people too, their political speech is protected. Twitter flagging President Trump’s posts with fact-checking tags is just them exercising their speech in competition with President Trump’s speech. This is the much vaunted “marketplace of ideas” of which conservatives are usually enamored.

As a matter of law Trump’s draft executive order is largely toothless because the text of Section 230’s Good Samaritan clause allows Big Tech companies to take “good faith” actions to “restrict access to … material” even when “such material is constitutionally protected.” Despite the opinion of legislators, there is not even a whiff of a political neutrality requirement. While such a requirement used to exist, it ceased being enforced in 1987 and was fully obliterated in 2011. The decision to cease enforcing this requirement was made by US President Ronald Reagan’s FCC Commissioner, Mark Fowler, because it was seen as violating first amendment protections.

Infringement by the government on freedom of speech is held in court to strict scrutiny. Part of the strict scrutiny standard is that the infringement promotes a “compelling government interest.” If the government exercises its authority over private individuals or groups under the auspices of protecting freedom of speech, what standards will the government ask be met? The entire point of rights like the freedom of speech is to permit persons acting in a private capacity to determine things for themselves. As many critics and advocacy groups have pointed out, allowing the government to set these standards is harmful to free speech rather than protective of it. Legislators appear to remember this only as it suits their political needs.