This article has a set of discussion questions tailored for classroom use. Click here to download them. To see a full list of articles with discussion questions and other resources, visit our “Educational Resources” page.

As the midterm election rapidly approaches, one thing is obvious—the number of women running for office is truly historic. There are 256 women running for Congress, 234 for seats in the House and 22 for seats in the Senate. The majority of the women running are Democrats. There are 197 Democratic female candidates and 59 Republican female candidates. The previous record for Democratic female nominees to the House was established in 2016, when 120 women were nominated, a record that is shattered by this year’s numbers. Historically, women have never comprised more than one-fourth of the House or the Senate. This year, that might change.

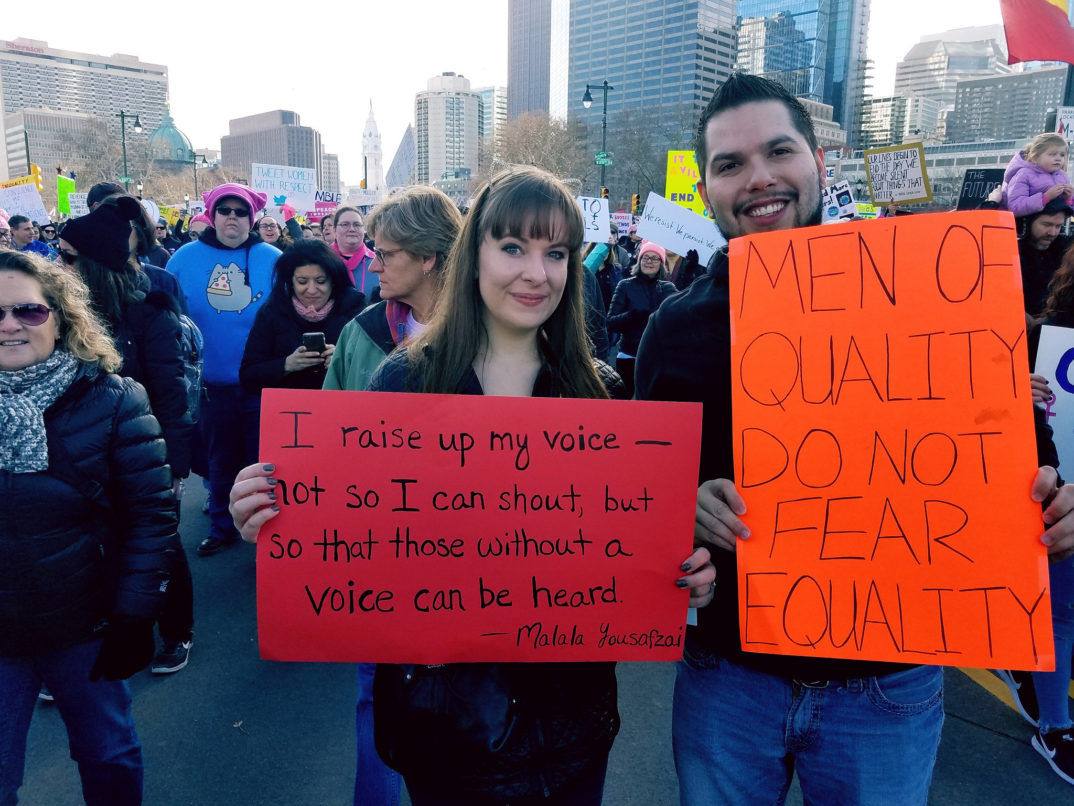

With the possibility of more female governance on the horizon, it seems like a good time to reflect on what this might mean for the country in both the short and the long term. One of the more immediate results of having more women in power might have been one of the main motivators for women to run for office in record numbers this year in the first place: a change in tone with respect to how women’s issues are discussed. To many, it seems as if there are no real consequences when it is revealed that important public officials discuss and treat women in demeaning, objectifying ways. If more women are in position to write and edit the script when it comes to how public officials talk about and treat women, we might be looking at a new normal.

If there were more women in power, it would make a tremendous difference when it comes to the habituation of children. Female children would be put in a position to see a new range of possibilities for themselves. If these female candidates are successful, becoming a politician might seem like a natural career choice for a young woman dreaming about her future. Male children being raised in a society with more female representation will never be led to believe that political power is held predominantly by men in the first place. A choice to become a politician will seem equally possible for young men, and they’ll be ready to come to the decision-making table and roll up their sleeves with both men and women.

If there were more women in power, decisions about women’s issues could be made with the benefit of the crucial female voice. Of course, not all women share the same opinions, but discussion generated by healthy disagreement among women with different backgrounds and experiences with women’s issues is crucial to constructing sound policy and legislation in these areas.

Of course, it’s not as if the dominant reason for electing women is so that they can have a say when it comes to issues that affect women. That women should be involved in discussion about women’s issues is a pretty minimum requirement for just, fair governance. A female perspective is crucial when it comes to all social policy.

It might be time for a revolution when it comes to our philosophy of power. There are different approaches to power, each of which might be appropriate in different domains and which may work together to regulate one another. We know that women provide the majority of both paid and non-paid care work. In our current political climate, that work is significantly undervalued. What if we came to recognize the value of care—and saw it for the tremendous source of power that it ought, rightly, to be? This kind of power is not a power over, but a power to, specifically, a power to help. A care relationship arises out of need. For example, a child may have needs for food, clean drinking water, and shelter, among other things. Parents, in their capacity as caregivers, have the power to help to satisfy those needs.

What if the popular understanding of the relationship between representative and constituent changed? Currently, we tend to have a pretty paternalistic conception of the way that political representation works. People vote along party lines and then largely check-out, trusting the elected official to make decisions in ways that are consistent with their values. Politicians, on this model, are given wide berth to engage in dubious political machinations and place themselves in the pockets of lobbyists. But care relationships don’t work this way. What would change if we came to view the relationship between the representative and the constituent as a relationship of care, where the power wielded by politicians was the power to help? Care depends on need, and addressing needs requires paying attention. So a politician fails to satisfy their obligation of care when, for example, they fail to respond to constituents who overwhelmingly express a need for change in firearm legislation. The representative would retain some autonomy and authority over the precise way in which this need gets pursued, but they can’t just ignore it altogether. If a child expressed an urgent and legitimate need for medical care, we’d view a parent as negligent if they didn’t attempt to satisfy that need to the extent that they were able. Should we respond any differently when it is our fellow citizens drowning themselves in debt to pay for essential medical needs while our representatives look on, unresponsive?

People have different personalities and interests and express power in various ways, irrespective of gender. We’ll avoid generalizing. But if, as the numbers bear out, women often voluntarily engage in care work regularly in an earnest desire to help, this new way of conceiving of power results in the conclusion that many women would be quite well-suited to take on the political mantle. In many of the locations in which women are running this year, they have little chance of being successful. But some races look promising. It’s a start.