As I explore in “The Unexpected Tension of Netflix’s Nanette,” Hannah Gadsby revolutionizes comedy with her show Nanette when she quits being funny. Gadsby works within a male-founded and dominated genre, using the same platform that so many white straight men before her have used to sell cheap jokes at the cost of marginalized groups.

Gadsby repeats occasionally during the hour-long show that she has to quit comedy. At first her proclamation seems like the central joke that the sketch keeps returning to; however, her assertion becomes to feel more real the more that people watch, and they may begin to wonder if her comedy is revolving around a truth. Midway through the show, Gadsby jokes that it does not look like she can quit comedy because she does not have a backup plan with just a 15-year-old art history degree on her resume. Gadsby goes on to say about the artists whom she studied: “They were dead then, they’re just deader.”

Gadsby discusses what she learned from her art history degree, explaining how she realized that women have two roles in the narrative of art: the virgin or the whore. Judged by sex, women see themselves through the male gaze in any introductory art history course. Men craft the pictures. Women lay naked on the bed. Men are the geniuses. Women are the models. Gadsby gives the example of Picasso, one of the most lionized artists in art history, providing one of his quotes: “Each time I leave a woman, I should burn her. Destroy the woman, you destroy the past she represents.” A prime example of a woman-hater that has reached historic idolization, Picasso and his infamous misogyny is often cast as tormented genius. “I understand the world that I live in because of art history,” Gadsby says. “I understand the world that I live in, and my place in it. I don’t have one.”As someone who is attracted to women, she does not fit into one of the two patriarchal categories that artists like Picasso worked to perpetuate.

Gadsby says in one of her jokes that she is often introduced “as that lesbian comedian.” Her identity separates her from other comedians because our society values heterosexuality and gender conformity. In one of her early self-deprecating jokes about lesbians lacking a sense of humor—the irony being palpable since Gadsby is the one providing comedy for the audience of an almost 6,000 seat theater—she comments, “That is not my joke. It is an oldie, oldie but a goldie. A classic, it was written, you know, well before even women were funny.” In the first half of her show, Gadsby provides a sample of the comedy that has motivated her decision to quit the career.

In order to work her way into comedy as a gender non-conforming woman, Gadsby has built her career on those jokes that do not belong to her because the genre of entertainment does not either. Gadsby asks, “Do you understand what self-deprecation means from somebody who already exists in the margins? It’s not humility. It’s humiliation. I put myself down in order to speak. In order to seek permission to speak. And I simply will not do that anymore. Not to myself. Or anyone who identifies with me. And if that means that my comedy career is over then so be it.” Patriarchal institutions are all about performing, conforming, and filling your destined role because they become incredibly challenging to change from the outside looking in.

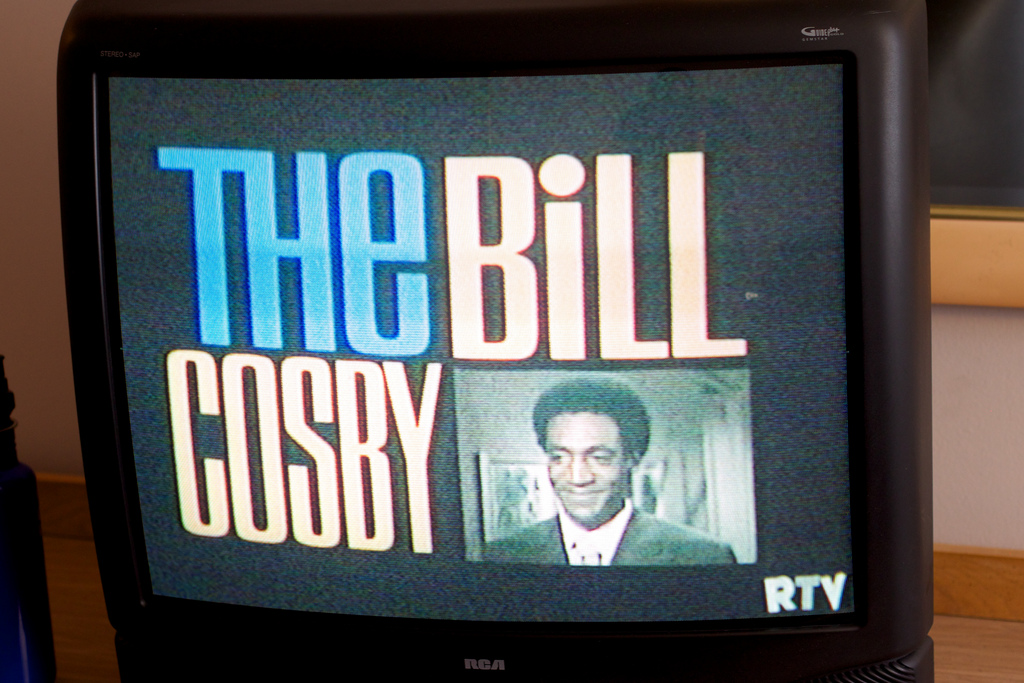

Later in the show Gadsby challenges this kind of “classic” humor: “Do you know who used to be an easy punchline? Monica Lewinsky.” One of the many jokes about Lewinsky’s sex life and weight comes from the famous comedian Jay Leno: “Monica Lewinsky has gained back all the weight she lost last year. . . . In fact, she told reporters she was even considering having her jaw wired shut, but then, nah—she didn’t want to give up her sex life.” Bill Clinton, then a 49-year-old married man with the most powerful position in the United States, had an affair with a 22-year-old intern. But the criticism, humiliation, and focus came down on Lewinsky’s body and sexual agency.

Jessica Bennett’s Time article, “The Shaming of Monica: Why We Owe Her an Apology,” details the “slut-shaming” humiliation that Lewinsky faced, including a Fox News poll in which 46 percent voted that Lewinsky was an “average girl” while the other 54 percent chose the second option, classifying her as a “young tramp looking for thrills.” Fox News did not invent that dichotomy just for Lewinsky. That average girl or tramp dichotomy has been around through centuries of art history, bringing us back to the virgin or whore. The main poll that came out about Clinton in the wake of his impeachment was his skyrocketing 73 percent approval rating.

Gadsby diverts her criticisms to the man who abused his power and her own industry that helped him get away with it: “Maybe if comedians had done their job properly and made fun of the man who abused his power then perhaps we might have had a middle aged woman with an appropriate amount of experience in the White House instead, as we do, a man who openly admitted to sexually assaulting vulnerable young women because he could.” History repeats itself when powerful men learn about what they can get away with and women learn that that their worth will be determined by which category they fit into: the virgin or the whore.

Returning to a discussion of art history, Gadsby not only compares Trump to Clinton, but also to Picasso. In the article, “Hannah Gadsby on how Picasso is the Donald Trump of the art world, and why we need to rethink art galleries,” Dee Jefferson elaborates on the connection between Trump and Picasso—two powerful and untouchable men—that Gadsby hints at during Nanette through her comment: “The greatest artist of the 20th century. Let’s make art great again, guys.”

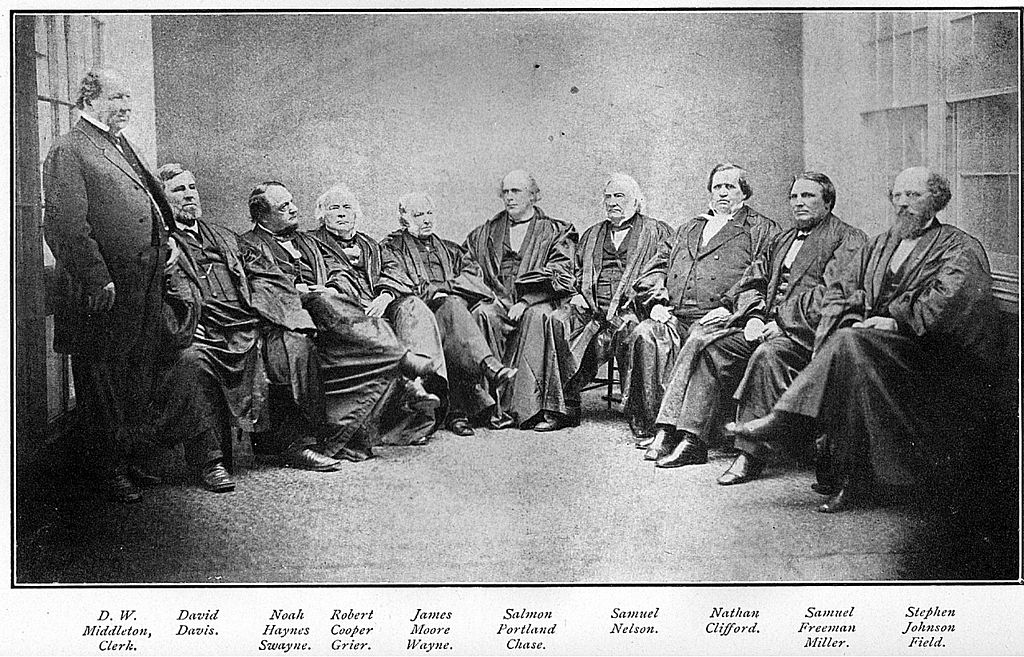

Gadsby brings up how she commonly receives advice to “[s]eparate the man from the art.” Yet that dissociation takes deliberate effort and a compromising approach to prioritizing what matters. In his article, published by The Telegraph in April of 2016, Mark Hudson, an art critic and writer, attributes the worsening of Picasso’s misogyny toward his first wife, Olga Khokhlova, whom he stayed with for 18 years: “As their relationship disintegrated and she became increasingly delusional, his depictions of her and women in general grew ever more hateful – tortured masses of teeth, limbs and vaginas.” Ten years into their marriage, Picasso began a relationship with an underaged girl, Marie-Thérèse Walter, that lasted nine years. Khokhlova’s suffering mental health in her relationship with Picasso does not make her to blame for Picasso’s hatred of women, but rather a victim of it. This representation of Picasso is not specific to Hudson alone, and I do not mean to criticize Hudson specifically. His article is one of the many examples of how victim-blaming comes naturally in our society in order to preserve a famous man’s reputation.

A common argument to preserve Picasso’s notoriety favors excusing his misogyny as a symptom of the time period: Picasso was just a product of his sexist environment. However, that sexism stays alive in how we frame, praise, and preserve his genius and reputation today. Hudson describes the 17-year-old Marie-Thérèse Walter—who met Picasso when he was 45—with unflattering superficiality: “[b]londe, of equable temperament and athletic physique – but completely ignorant of art – Walter was immortalised in images of melting, idyllic eroticism in which we feel her guiltless enjoyment of her own sensuality and the artist’s complete satisfaction in regarding it.” Even today, we still judge a 17-year-old girl in terms of her appearance and sexuality through the male gaze.

In his Vanity Fair article, John Richardson writes about Walter and Picasso’s courtship: “Although she always claimed to have resisted Picasso for six months, she was sleeping with him a week later. They needed to be very discreet, for she was six months under the conventional age of consent.” Richardson turns a predatory, law-breaking situation into a bit of gossip. Blaming Walter’s inability to “resist” Picasso’s seduction, Richardson liberates Picasso from any wrongdoing. In his language, Richardson implies that Walter did not fit in the Fox News “average girl” category. The problem with this language and logic is that Richardson is talking about a minor. The phrase “conventional age of consent” downplays the fact that she was a legally underaged individual, unable to give consent legally. The fact that their affair was secret — so secret that Picasso would take Walter to have sex in attics in various estates or in the garden shed behind her mother’s house — was not for modesty’s sake, but due to its criminal nature.

We do not cast Picasso as a sexual predator or a power-abuser using his age and fame to manipulate young women, but rather as a man dabbling in his appetites and finding muses to provoke his artistic genius. Gadsby discusses how Picasso justified the fact that Walter was not even half his age by claiming that they were both in their prime: his art career was flourishing, and Walter had youth and beauty. Perhaps the reasons that Walter “offered Picasso little on an intellectual level”—as Hudson claims—is due to their 28 year age difference and her limited life experience.

Similarly, Picasso’s affair with Walter parallels the power discrepancy between Lewinsky and Clinton.“[Clinton] was the most powerful man on the planet,” Lewinsky recalls. “He was 27 years my senior”—an age gap that is just a year shy of Picasso and Walter’s. She continues, “He was, at the time, at the pinnacle of his career, while I was in my first job out of college.” The media and comedians slandered Lewinsky’s decision-making, failing to spotlight the judgement of the 49-year-old man with the job of making decisions for the future of a powerful nation. By adjusting our perspective from the innately patriarchal lens that so often filters the story to a rational and sympathetic approach, a different narrative arises out of Walter and Picasso’s and Lewinsky and Clinton’s affair.

Walter’s place in history melds with Picasso’s representation of her sexuality. We see her through his eyes, and she lives in the shadow of Picasso’s reputation. Hudson’s article provides a summary of each Picasso girlfriend and model at the end: after a sentence about she and Picasso met, Hudson summarizes “She gave him a daughter, Maia, in 1935, at about the time she was supplanted in Picasso’s affections by Dora Maar. She hanged herself in 1977.” This barebones synopsis of her life provides the only mention of her suicide.

Instead of analyzing the unhealthy strain of Picasso’s manipulation on two of his mistresses, Hudson describes the two women—one who would later have “suffered a complete mental collapse” and the other who would eventually kill herself—with reductive nonchalance and a sort of humor: “When Maar and Walter later met in his studio, the ensuing argument degenerated into an all-out catfight between the two women, an incident Picasso later described as one of his ‘choicest memories.’” With this kind of degrading diction, these two very young women’s suffering becomes solidified as self-serving entertainment for Picasso — who sought control over both women.

Hudson titled his article “Pablo Picasso: women are either goddesses or doormats”—a quote that the 61-year-old Picasso told a 21-year-old student and mistress, Françoise Gilot. Hudson affords Gilot the most flattering summary even though it relies on backhanded compliments: “This young aspiring artist – just 21 when they met – seems to have handled Picasso’s cruelties and perversities with amazing deftness, and was the only woman to leave him entirely voluntarily, with her dignity more or less intact.” Even though she does fit into the “virgin” category in the art historical narrative, affecting her “dignity” as Hudson hints at, Gilot earns Hudson’s approval through her ability to endure Picasso’s torment.

Deeming Jacqueline Roque as the last of Picasso’s mistresses and “the one most in control,” Hudson also credits her because she “finally got Picasso to behave, and created a tranquil base for his last years.” Roque married Picasso in 1961, but Hudson does not linger on the fact that she also eventually killed herself. About Roque, Hudson’s article ends on the idea: “Like the other six women, she had collaborated in what is arguably the greatest artistic oeuvre of all time. Whether it was worth the pain, only she would be able to say.” Despite the clear suffering that they encountered in their relationships with Picasso, these women reached the peak of traditional women’s involvement in art historical memory: model to the founder of Cubism.

Was Picasso’s Woman in Hat and Fur Coat worth Walter’s life? Was preserving Clinton’s approval ratings worth Lewinsky’s public shaming and humiliation? As Gadsby says, we need to stop prioritizing a man’s reputation over a woman’s potential. Khokhlova, Walter, Marr, Gilot, Roque, Lewinsky, the upwards of 80 women who have accused Harvey Weinstein of sexual predation, the 18 women—according to Time—who have accused Trump of sexual misconduct, and all the women who have been shamed, silenced, and prevented from speaking out against a powerful man deserve justice. “A 17 year old girl is just never ever in her prime. Ever,” Gadsby asserts. “I am in my prime. Would you test your strength out on me?”

My series on Hannah Gadsby’s Nanette will continue in my next article, in which I will analyze two of Picasso’s most revolutionary works, his Portrait of Gertrude Stein and Les Demoiselles d’Avignon. I will address the question of whether we can truly separate the man from the art and if that objectivity would be more harmful or beneficial.