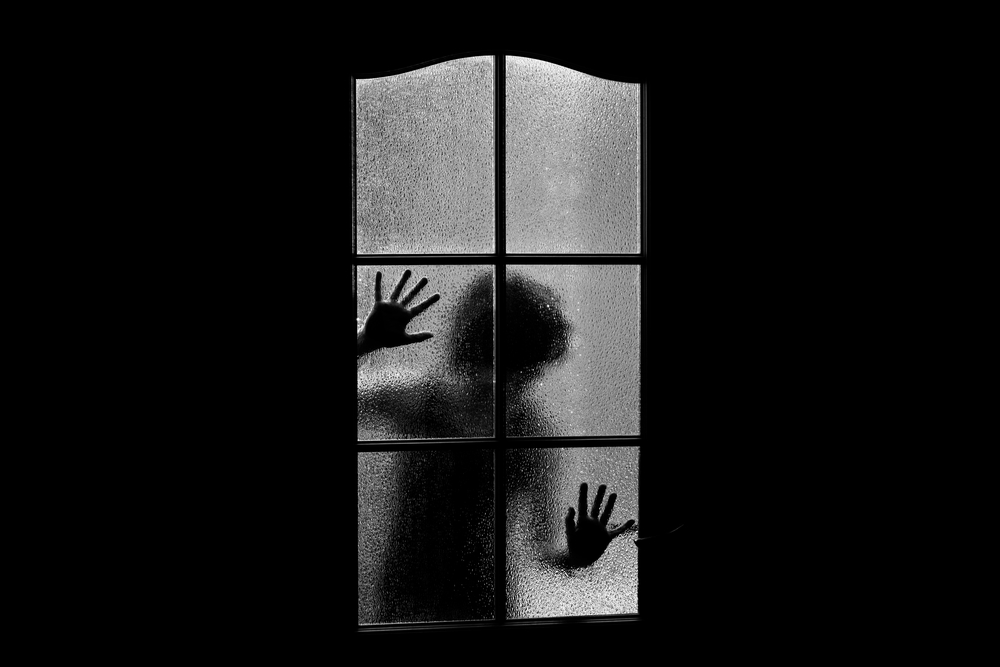

Since 2005 Russ McKamey has been running McKamey Manor, an extreme horror attraction. When patrons sign-up for the tour they are signing-up for being physically and psychologically mistreated. Before participating, patrons must go through extensive interviews, a medical examination, and sign a long legal waiver. However some participants complain that the experience is too extreme and that the legal waiver does not excuse their behavior. The nature of the attraction brings up a host of issues concerning the nature and extent of consent.

A waiver is a voluntary surrender of a right or opportunity to enforce a right. Many horror attractions require patrons to sign a waiver before entering, in which the participants acknowledge that they are knowingly taking on the risk of various losses and relinquish the right to seek damages they may suffer while attending the attraction. For example, if a person who attended a horror attraction suffered from a heart condition and experienced a heart attack during their participation, they would not be able to sue that attraction for any medical expenses incurred as a result of that heart attack. In the case of McKamey Manor the waiver is reportedly about 40-pages long. In addition to the waiver, potential patrons are required to watch videos of other people’s experiences at McKamey Manor. The participants in these videos all ask to have their experience ended prematurely, and advise the potential participants that they “don’t want to do this.”

But does it follow that potential participants, duly informed of what may happen to them, truly consent to be buried alive, forced to ingest their own vomit, held under water, cut, struck, and verbally abused? Not necessarily. Not even a signed legal form, or other explicit signal of consent automatically creates genuine consent. There are several conditions which render void apparent consent such as when no genuine choice is available to participants or when the participant is offered something that undermines their ability to make rational decisions. McKamey Manor offers participants $20,000 if they can survive the entire experience (which is of variable length, ranging from 4 – 10 hours). Even in the longest scenario a successful participant would stand to make $2,000 per hour of their time — an inducement that undermines a person’s ability to think clearly.

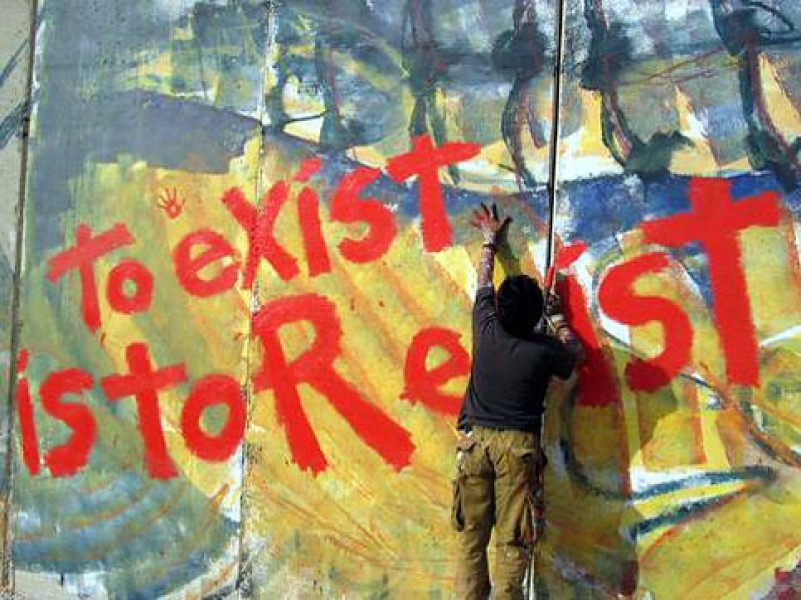

While recent McKamey attractions allow participants to create safe words to automatically end their horror experience, this was not always this case. And McKamey patron Amy Milligan claims that even when she begged the actors to stop, they continued to torment her. If a person cannot end the experience at will — if they are at the mercy of the actors creating the experience — then that person has been robbed of their autonomy, even if only for a limited time. This creates another type of situation in which the explicit consent signal, in the form of the waiver, is a legal fiction. It is not possible for a person to fully waive their autonomy, as doing so would be to essentially sign themselves into slavery.

The idea that such “voluntary slavery” could exist is discounted as a possibility by philosophers with views and methodologies as different as Jean-Jacques Rousseau and John Stuart Mill. Rousseau argued that once a person becomes a slave by losing all autonomy, they cease to be a moral agent at all. As such to consent to being a slave would be to consent to no longer being a moral or legal person. Mill argued that voluntary slavery was an exception to his harm-to-others principle, which stated that any person could do as they pleased so long as they did not harm someone else. He claimed that although a person attempting to sell themselves into slavery may not be causing harm to anyone but themselves, it nonetheless stood in contradiction with the whole point of the harm-to-others principle — to maintain maximum individual liberty.

Though McKamey Manor residents do not sign themselves away into permanent slavery, they do “waive” their autonomy for a limited amount of time. Importantly, the effective duration of this “waiver” is determined not by the participants, but rather by the actors. Moreover some of the experiences patrons are subjected to are essentially torture. Here again the substantiveness, or, at least, relevance, of patrons’ consent is dubious. Consider waterboarding, a form of simulated drowning. (McKamey contends that no participants are waterboarded, but admits that they will be made to feel like they are drowning — a spurious distinction.) The problem with military detainees being waterboarded is not that they weren’t asked for their permission first. Indeed lack of permission is not the sole moral shortcoming of any form of torture. The problem is instead the nature of the activity and the relationship it creates between people: a relationship in which one person is inflicting suffering an another for enjoyment or profit.

McKamey and his defenders claim that the screening and waiver process creates a situation in which McKamey Mansion patrons consent to a prolonged period of physical and emotional abuse. However there are some things that no waiver, no matter how length and legalistic can create consent for. A person’s autonomy is inalienable. This doesn’t just mean that it cannot be taken away, but also that it can’t be given away.