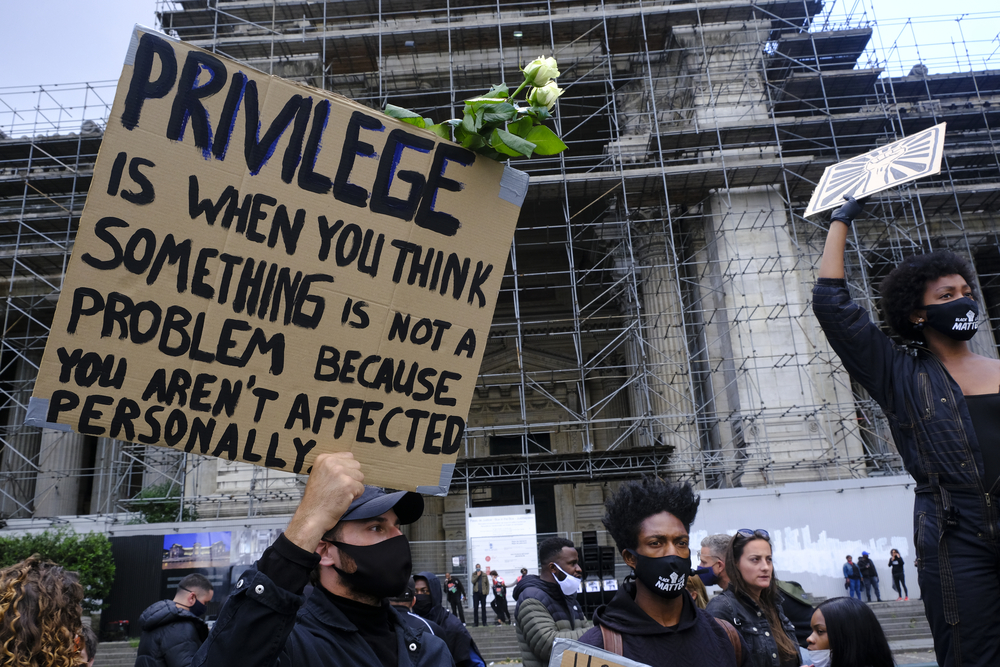

The video of George Floyd dying after nine long minutes by suffocation at the hands of a Minneapolis police officer is gruesome, sickening, and has prompted countless people to action. The officers responsible for his death have been arrested and charged. In response to protests, numerous state and local governments are instituting police reforms. Black people have been killed by police before. But given that this particular video of unambiguous violence perpetrated by police has been circulated so widely, is so appalling, and instigated such a fierce response, this example stands out.

From this fact, a rough argument may be sketched. Sharing videos of horrifying violence prompts positive social change, so let’s share more videos of horrifying violence. If such a video is helping to stop police violence, why not share other violent videos to help stop gang violence, war violence, and terrorist violence? In fact, why not share videos showing the effects of structural violence, videos of suicides due to social isolation and industrial accidents due to lack of regulation? Scrolling through Twitter or Facebook, one might see a video of a cute baby taking her first steps, then a video of a terrorist execution, then a video of a bunch of newborn puppies, and a video of a young man sticking a gun in his mouth and pulling the trigger. Even if you think it is good that the Floyd video was widely shared, you probably don’t support turning your morning scroll through social media into such a traumatic experience. To understand this apparent contradiction in instinct, let us consider how violent content is treated on social media today and the arguments for and against censoring it on these platforms and in general.

First, we need to consider what “violent content” is and how it is understood by social media companies. While there may be an intuitive sense that violent content only includes uses of force for the purpose of causing harm, social media companies take a more expansive view. Twitter, for example, includes under the category of “graphic violence,” accidents and any “serious physical harm.” But, these companies also tend to distinguish between what Twitter calls “graphic violence” and “gratuitous gore,” as though there is some amount of violence or gore that is not in some way “gratuitous” to our experience of the world.

While graphic violence may include “bodily fluids including blood, feces, semen,” and is only hidden behind a “sensitive media” label and blur, “gratuitous” gore, which includes dismemberment, mutilation, burned human remains, and exposed internal organs and bones, is banned completely. But what exactly is the meaningful difference between these two categories? For example, a decapitation would certainly count as gratuitous gore and would be extremely off-putting. But, the video of Floyd being killed is merely graphic violence, even though it can easily be just as off-putting, if not more so. In fact, while a decapitation may be quick and relatively painless, Floyd died slowly of suffocation. Why is one “gratuitous” and not the other? Why is one censored and not the other?

From the start, companies can have two kinds of motivations for doing anything: moral ones and amoral ones. Either they do something because it is right or thoughts of right and wrong simply don’t factor into their decision. Twitter presents a moral argument for their censorship. They say that “We prohibit gratuitous gore content because research has shown that repeated exposure to violent content online may negatively impact an individual’s wellbeing.” Twitter does not make clear what they mean by well-being but if they mean an immediate sensation of feeling good or ill, their argument is trivially true. Only a sadist really enjoys the suffering of others and has their immediate well-being improved by viewing it.

And there might be a legitimate basis for Twitter’s claim. There is some evidence that regular viewing of violence can be desensitizing, though “regular viewing” here means in excess of two hours every day and none of the science is settled. But, there is also an obvious profit motive for Twitter’s censorship—if you associate negative feelings with your use of Twitter, you are unlikely to use it as frequently, and fewer users means less ad revenue. Regardless of the morality of this censorship, Twitter is motivated to censor for the sake of profits. So then, what are the moral reasons that could support this sort of censorship?

To answer this question, let’s first consider the odd bunch of people who do seek out violent content, taboo gratuitous gore in particular, to watch. One particularly popular community of these people was the Reddit group r/watchpeople die, which had over 400,000 members before it was banned. At that size, it is difficult to chalk the membership of that group up to just sadists, sociopaths, and other such extraordinarily deviant people. In fact, the moderators and power users of this subreddit were pretty much normal people, some married, plenty having friends. They didn’t fit the stereotype of obsessive death and gore watchers.

In fact, Rule #3 of the subreddit (as shown in this Wayback Machine archive of the subreddit’s homepage on September 20, 2018, shortly before its quarantine) included this expectation, bolded by the mods to highlight it: “Be respectful of the dead! This is important. Human beings have lost their lives. This subject matter is not to be taken lightly.” The subreddit also described itself as “a community for documenting and observing the disturbing reality of death” and as “not intended to be a shock or gore subreddit.” Finally, they referenced two famous philosophical ideas: “Memento mori,” the Latin Stoic maxim to always remember one’s inevitable death, and “Maranasati,” a similar idea in Buddhism. Gratuitous gore is often referred to online as “gore porn” as the basis for viewing it is thought to come from a similar place as the animalistic urge to view other kinds of pornography. However, in light of the seemingly principled basis for this community, it is tough to say that all viewing of gratuitous gore is pornographic.

Sue Tait, a lecturer in the field of mass communications at the University of Canterbury, elaborates on this idea in her article, “Pornographies of Violence? Internet Spectatorship on Body Horror.” She considers four different ways people in these sorts of communities interact with gratuitous gore. She refers to these as four kinds of gazes viewers have:

“I identify a range of spectatorship positions [viewers] take up, including: an amoral gaze, whereby the suffering subject becomes a source of stimulation and pleasure; a vulnerable gaze, where viewers experience harm from graphic imagery; an entitled gaze, where viewers frame their looking through anti-censorship discourses; and a responsive gaze, whereby looking is a precedent to action.”

To contextualize these gazes, let’s consider some examples from before. The amoral gaze would be the one taken up by the sadists. The vulnerable gaze is the one Twitter worries about its viewers having-they worry people will associate the “hurt” they feel at viewing gratuitous gore with the site itself and stop using it. The r/watchpeopledie community’s focus on “documenting and observing the disturbing reality of death” would be an example of the entitled gaze. And last but not least, the responsive gaze would be the one taken up by those who were prompted to action by the video of Floyd’s death and any one who would be prompted to similar action by similar, but gorier, content, like many on r/watchpeopledie were.

With the idea of these different kinds of gazes in mind, we can now construct a variety of arguments for and against the censorship of violent content.

According to virtue ethics, we might support censorship of gratuitous gore if it seems that regular exposure to gratuitous gore encourages vices in viewers. For example, if conclusive research comes out showing that exposure to violent media causes people to be more aggressive, cruel, or unempathetic, that would be a reason to support censoring gratuitous gore, the most extreme form of violent media. (In particular, we might worry about how this media influences the character of children whose morals are viewed as being particularly malleable.) This would be particularly true if a community encouraged people to take up an amoral gaze.

On the other hand, we might oppose the censorship of gratuitous gore if it seems that same exposure promotes virtue, rather than vice, in the viewers. If viewers take up a responsive gaze, rather than an amoral one, people may be encouraged to be more compassionate. As Stalin is reported to have said, “If only one man dies of hunger, that is a tragedy. If millions die, that’s only statistics.” Seeing the “disturbing reality of death,” over and over again, be it by hunger or by violence, might prevent people from losing touch with the horror of various kinds of violence and actually work to take action as they did with police violence after seeing the video of Floyd’s murder.

Immanuel Kant, the father of deontology — morals based on duties — made a creative argument against the abuse of animals that could be used to justify the censorship of gratuitous gore. While Kant did not believe animals had rights, or even any kind of consciousness, he still opposed sadistic animal abuse saying, “If any acts of animals are analogous to human acts and spring from the same principles, we have duties towards the animals because thus we cultivate the corresponding duties towards human beings.” In short, we shouldn’t abuse animals pointlessly lest we become able to do the same to people. In the same way, if repeated exposure to gratuitous gore hampers the cultivation of our duties toward people (as would be the case upon taking up the amoral gaze), such as not to murder them, then censorship of gratuitous gore would be justified.

But, deontology can also be used to oppose the censorship of gratuitous gore. Those who take up an entitled gaze might argue that we have a duty to uphold free speech or that we even have a duty to “document” deaths, for various purposes. People might also have a duty to bear witness to the reality of death for some further end as according to the maxim “Memento mori.”

Finally, we can give consequentialist arguments for and against censorship. If, on the whole, the viewing of gratuitous gore leads to more people doing harm to each other, then it should be censored. If not, if, according to the responsive gaze, people’s viewing leads to great social change, then it absolutely should not be censored.

This argument is especially powerful in an affluent nation like the United States. If you are an American, and if you are just a little lucky, you will have to see only a few people die, you will only attend a handful of funerals, and those funerals you do attend will recognize the deaths of people who we think were more or less supposed to die, that is, the elderly. But, Americans are an exception and though we can hide from death for most of our lives, the world is not a happy place where only those who have lived long lives, or who get unlucky with serious diseases like cancer, have to die. All sorts of horrible causes of death, from childbirth, infectious disease, war, and industrial accidents, are still very common in the Global South. You can find a particularly horrifying intersection of all of these in the Democratic Republic of the Congo where resource conflict has led to widespread poverty, civil war, and unsafe mining operations. But, some combination of these horrors can be found in most areas of the world.

We are terribly desensitized to all these horrors as these deaths are reduced to mere numbers. Few Americans have seen the effects of poverty, war, and sickness in these far away places. And, as they say “out of sight, out of mind.” If only a small portion of people take up the responsive gaze and stand up against these atrocities, and actually manage to remedy some of them, that would be an enormous consequentialist benefit that outweighs all the temporary harm it does to the “well-being” of comfortably, relatively wealthy (on the world scale), American viewers.

Overall, a violent video is not moral or immoral in isolation. Rather, the viewing of violent videos may be moral or immoral depending on the context. The morality of censoring gratuitous gore and other violent content may also depend on human nature. If most people, most of the time take on an amoral gaze or vulnerable gaze when viewing violent media, then by most accounts, censorship is justified. But, if people are basically good, then they might mostly take on the responsive gaze and untold benefits would result from ending the censorship of violent content. While it very well may be that some or all violent content deserves censorship, we ought to examine our reasons for censoring it. We ought to consider whether that censorship has a true moral basis or whether viewing violence is just uncomfortable, forcing us to reflect on the horrors of the world in a way from which we are usually, blissfully, isolated.