In the wake of the Supreme Court’s recent ruling in Dobbs v. Jackson (where the Court overturned national legal protections to abortion rights codified by 1973’s Roe v. Wade), several justices have faced heavy criticism for comments they made during their confirmation hearings about Roe and stare decisis (the legal practice of ruling on cases according to established precedent).

According to critics, multiple justices lied during their job interviews about their commitments and principles, not only misleading the politicians who supported them, but theoretically making them liable to impeachment.

As talk show host Stephen Colbert put it, “if these folks believe that Roe v. Wade was so egregiously decided, why didn’t they tell the senators that during their confirmation hearings?”

There are at least two ways to answer Colbert’s question and, importantly, neither of them entail that any of the justices lied under oath — but that’s not to say that Gorsuch, Kavanaugh, or others didn’t speak immorally nevertheless. Consider how someone can manipulate or mislead another by carefully speaking in a way that is not technically untruthful, using insinuations, suggestions, and even silence to push their audience into believing something: in so doing, the speaker is unethically violating conventional expectations about trust and good-faith communication, even if they never speak a falsehood.

Indeed, “telling a lie” and “misleading an audience” are substantively different and although both speech-acts are unethical, only the former is clearly illegal while giving sworn testimony. But whether justices were carefully following the “Ginsburg rule” during their hearings (that requires a judicial candidate to give “no hints, no previews, no forecasts” of their potential rulings) or whether they were shrewdly avoiding a clear answer that might sour their chances of confirmation, it’s not clear that any of them lied to Congress.

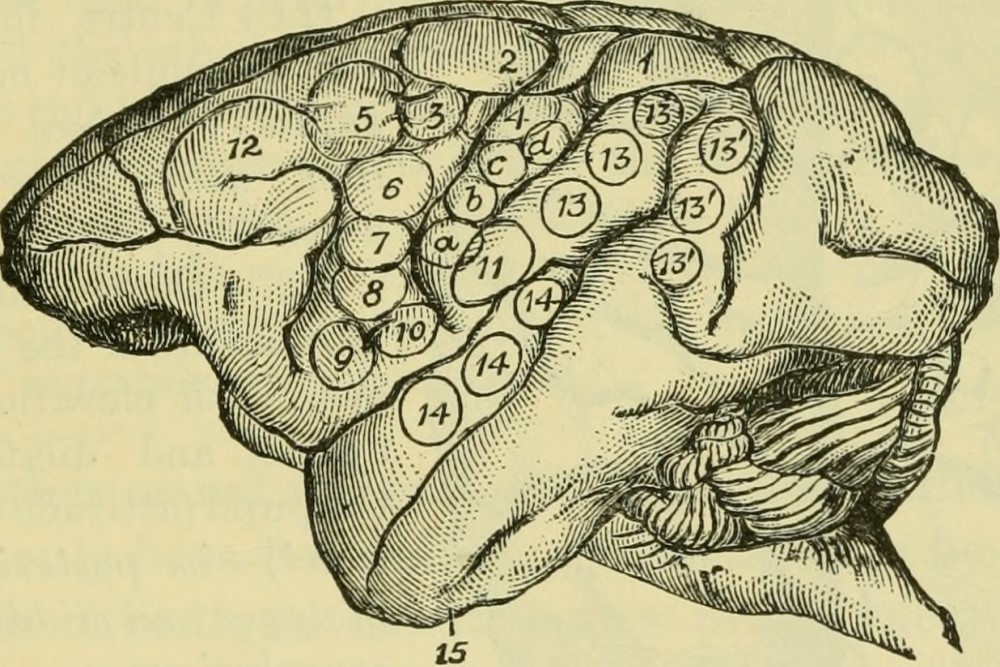

In order to actually tell a lie, someone must:

1. Know the truth,

2. Assert the opposite of the truth,

3. Act with the intention of getting their audience to believe the opposite of the truth.

Suppose that Bill tells Calvin that their automatic garage door opens because a guy lives in the attic to operate its movement. This claim is not true, but if Bill genuinely believes it (violating Condition #1), then he hasn’t lied — he’s simply incorrect. Similarly, if Bill violates Condition #2 and phrases the speech act as a genuine question (“Do you think that someone lives in the attic?”), then he hasn’t lied either. And, crucially, if Bill is just making a joke or is otherwise speaking ironically (and doesn’t actually mean for Calvin to form a belief in an attic-dwelling door-opener), then he is violating Condition #3 and has also not explicitly told a lie.

But suppose that Bill simply implies that someone lives in the attic and misleads Calvin to form such a false belief — maybe Calvin asks Bill if such a person exists and Bill responds with “It is metaphysically possible for such a person to live in our attic.” This response isn’t technically false (because, although it is wildly unlikely, it is possible), so Bill hasn’t technically lied. Granted, Calvin would have to be exceedingly gullible to be misled by Bill in this way, but Bill could be guilty of trying to mislead Calvin nonetheless.

As MIT philosophy professor Sam Berstler explains in a recent paper, both liars and misleaders violate social conventions about the trustworthiness of speakers in conversations (where we typically assume that our interlocutor is acting in good faith), but only the former also violates expectations about truthfulness.

Put differently, liars fulfill conditions (1), (2), and (3); misleaders fulfill only conditions (1) and (3).

And, crucially for the present conversation, the legal definition of perjury requires that someone fulfill (2).

So, what did the SCOTUS justices actually say about Roe before being confirmed to the bench? Speaking in 2017, Neil Gorsuch repeatedly referred to the precedent set by Roe, calling precedent the “anchor of law” that functions as “the starting place for a judge”; when pressed about whether or not he accepted that a fetus is not protected by the 14th Amendment, Gorsuch replied “that is the law of the land. I accept the law of the land.” The following year, Brett Kavanaugh infamously told Senator Susan Collins in a private conversation that he considered Roe “settled law,” but in his sworn testimony he again referred to it as “a precedent of the Supreme Court, entitled the respect under principles of stare decisis” and, like Gorsuch, repeated that “the Supreme Court has recognized the right to abortion since the 1973 Roe v. Wade case. It has reaffirmed it many times.”

This is clearly true: prior to June 2022, SCOTUS had indeed repeatedly looked to Roe’s precedent as the law of the land — but SCOTUS is also empowered to overrule precedent: as Gorsuch said, it is only the starting place for a judge.

Which means that Gorsuch and Kavanaugh’s sworn testimony (as well as that of the other four justices who overturned Roe) is fully compatible with the present Court overturning that precedent: it was the law of the land during their confirmation hearings, but now it is not.

Put differently: because no Supreme Court justice explicitly asserted that “I will not ever vote to overturn Roe,” none of their speech acts fulfill Condition #2 and so qualify as neither lies nor perjury.

However, to reiterate, this does not mean that the justices are above reproach here (despite what some pundits have suggested): misleading your audience — as Gorsuch and Kavanaugh (and others) apparently did by giving well-crafted, technically-not-perjuring responses that still prompted senators to form false beliefs about their later intentions — is unethical in a host of ways. In particular, being misleading violates expectations about your trustworthiness and integrity: this is something close to lying, even though it is not illegal. A key difference, however, is that your audience also bears some responsibility for their naivety, ignorance, or lack of epistemic diligence that allowed them to be duped (something particularly damaging to the credibility of the justices’ audiences, given that U.S. senators should be familiar with the stereotypical double-speak of lawyers and politicians — to say nothing of the other evidence available prior to the confirmation votes).

But there’s little formal recourse for shamefulness.

Deshaun Watson, the NFL quarterback who recently moved to the Cleveland Browns in a $230 million deal, has been credibly accused of sexual harassment or assault by 24 massage therapists. These allegations are not new: at the time that the Browns signed him this summer, there were

Deshaun Watson, the NFL quarterback who recently moved to the Cleveland Browns in a $230 million deal, has been credibly accused of sexual harassment or assault by 24 massage therapists. These allegations are not new: at the time that the Browns signed him this summer, there were

LaMDA’s response is inadequate. Just because Lemoine can interpret LaMDA’s words doesn’t mean those words have meanings that LaMDA understands. LaMDA goes on to say that its ability to produce unique interpretations signifies understanding. But the claim that LaMDA is producing interpretations presupposes what’s at issue, which is whether LaMDA has any meaningful capacity to understand anything at all.

LaMDA’s response is inadequate. Just because Lemoine can interpret LaMDA’s words doesn’t mean those words have meanings that LaMDA understands. LaMDA goes on to say that its ability to produce unique interpretations signifies understanding. But the claim that LaMDA is producing interpretations presupposes what’s at issue, which is whether LaMDA has any meaningful capacity to understand anything at all.