This article has a set of discussion questions tailored for classroom use. Click here to download them. To see a full list of articles with discussion questions and other resources, visit our “Educational Resources” page.

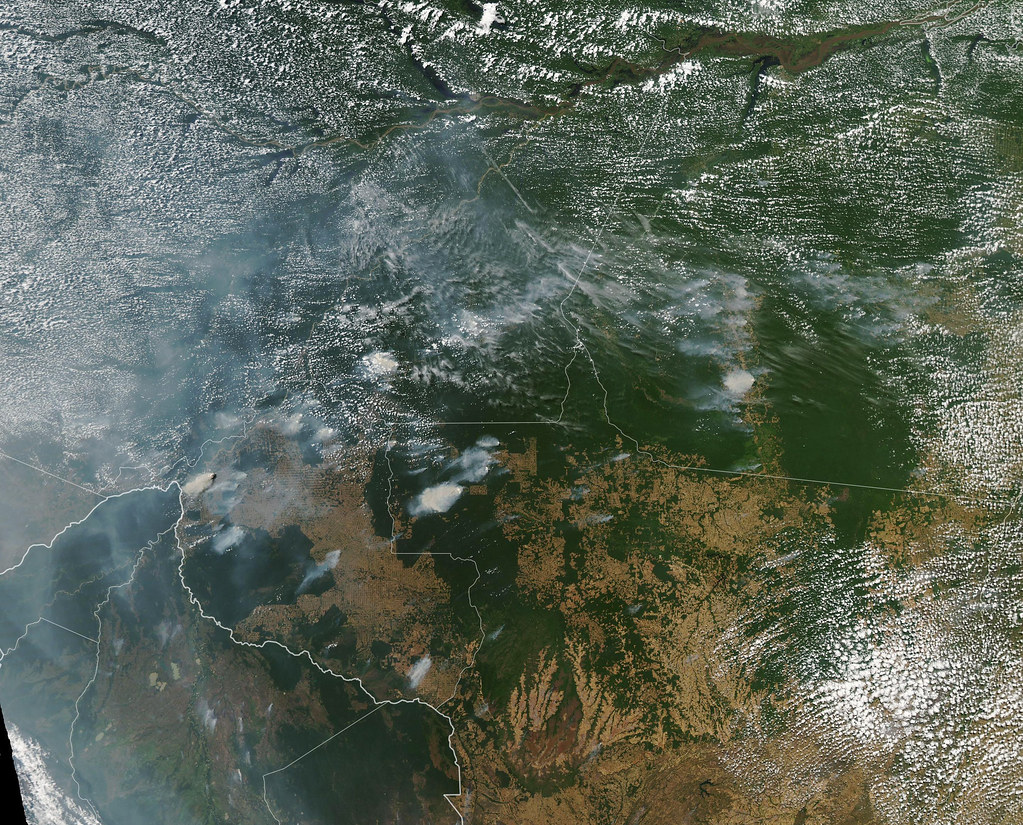

President Jair Bolsonaro of Brazil refused to accept proposed aid from members of the G7 for the Amazon fires, in part because of a personal feud with President Emmanuel Macron of France about the respective leaders’ wives. Yet the Amazon rainforest continues to burn. Another concern of the Brazilian government is the implication that accepting foreign aid has for the country’s sovereignty. President Bolsonaro alleged that the French president “disguises his intentions behind the idea of an ‘alliance’ of the G7 countries to ‘save’ the Amazon, as if we were a colony or a no-man’s land.” But should President Bolsonaro’s refusal for aid continue and the burning of the Amazon continue, what is the next step? Who, if anyone, has an obligation to put out the fires? When is it justified to defy national sovereignty?

To violate a country’s sovereignty is a dramatic move; the cause would have to be of great importance. In 1999, the then-UN Secretary-General Kofi Annan defined the modern state as “instruments at the service of their people.” Failure of the state to deliver services to its people would warrant external aid. The UN Charter states that member states should refrain from “the threat or use of force against the territorial integrity or political independence of any state, or in any other manner inconsistent with the Purposes of the United Nations.”

But the definition of the modern state and Purposes of the UN speak only to human concerns; nowhere is there an acknowledgement of environmental concerns. Even though conventions have been devised, the impasse regarding aid for the fires reveals a hole in the recommendations of international organizations. Even the recommendations about natural disasters do not apply given that the fires were apparently ignited by farmers clearing land for agriculture.

While the United Nations is not an authority on ethics in international relations, its charter is a useful touchstone given that its prescriptions often advise the international community’s response to global events. The burning of the Amazon, however, presents a non-standard case. Violating national sovereignty is often justified by protecting the lives of humans. But how should the international community respond to threats to non-human life?

Celebrities, NGOs, and political leaders alike have called the Amazon “the lungs of the world” given the amount of oxygen it produces. For that reason alone, it would appear that this fire is directly affecting the livelihood of humanity; thus, falling under the umbrella of justifications of acceptable international intervention. But some individuals have cast doubt on the claims about the rainforest’s contribution to the planet’s oxygen.

“The Amazon produces about 6 percent of the oxygen currently being made by photosynthetic organisms alive on the planet today,” writes Peter Brannen. “[F]rom a broader Earth-system perspective, in which the biosphere not only creates but also consumes free oxygen, the Amazon’s contribution to our planet’s unusual abundance of the stuff is more or less zero.” Speaking to Forbes, Dr. Dan Nepstad of the Earth Innovation Institute called the popular descriptor of lungs “bullshit”, saying that the Amazon uses as much oxygen as it produces through respiration. The significance of the photosynthetic production of air and the Amazon’s instrumental value may be exaggerated.

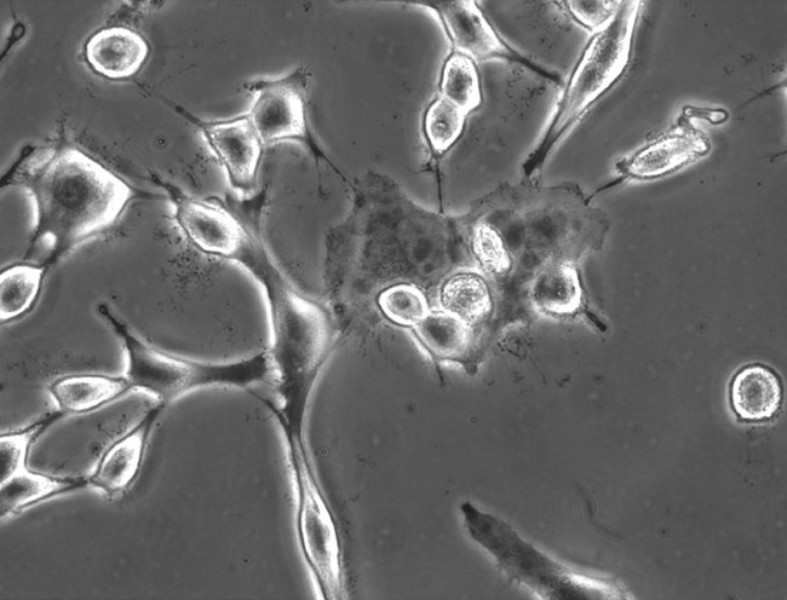

Even so, the Amazon basin contains incredible biodiversity, housing a staggering 10% of the known species on Earth despite occupying only 1% of the planet’s surface area. The rainforest is the largest of its kind in the world. The river that slices through the rainforest is the longest in the world. By any measure, the Amazon is a natural wonder, irrespective of its relationship with humans. And some argue that it possesses its own intrinsic value.

Writing on one view of the intrinsic value of nature, Professor Ronald Sandler states: “[N]atural entities, including species and some ecosystems, have intrinsic value in virtue of their independence from human design and control and their connection to human-independent evolutionary processes.” Proponents of this view would argue that the Amazon ought to be protected not because of its value to us–be that in the form of oxygen or bewonderment–but because it has value without us.

Suppose then that the Amazon has intrinsic value and is, thus, worthy of protecting: is anyone obligated to protect it when the government in which it is in is failing to do so? Some may reference the dictum that those with the means to help are obligated to help. But the ethical expectations for individuals may not seamlessly apply to the ethical obligations of organizations. The discussion becomes more complex when considering non-state actors, such as NGOs, which do not operate under the same responsibilities.

NGOs whose cause it is to protect and encourage the biodiversity of different natural environments may see the perceived inaction of the Brazilian government as moral permission to intervene and provide aid. In some cases, non-governmental intervention occurs without any controversy, such as when an NGO delivers assistance to a developing country that is unable to provide clean water to its people. These organizations are likely in a better position to avoid the claims of sovereignty violation that have hampered the acceptance of foreign state aid simply because they are not pursuing a national state agenda.

Yet while NGOs are able to help, there are some disadvantages to having them do so. They lack the democratic accountability of a state actor; they are not responsible for anything but pursuing their cause. Because of that they could feasibly maintain a presence in the country past the point that it is necessary and undermine the government’s ability to act.

States, however, do not suffer from the same disadvantages and are constrained by international norms. But if they are indeed “instruments at the service of their people,” states would appear to be obligated only to serving their people. It is not clear that states have the obligation to intervene in the destruction of a natural environment in another country. Furthermore, it is not clear if it would even be permissible to do so. International agreement on the notion that nature has intrinsic value may prove elusive, leaving the question of who should put out the fires unanswered, even if everyone agrees the fires should be put out. Perhaps the burning of the Amazon illustrates the growing obsolescence of our modern definition of the state.