The articles are everywhere. Headlined by an eye-catching, caps-locked “WATCH,” they offer the reader the opportunity to watch someone die. The person in this case is Samuel Dubose, a Cincinatti resident killed by a policeman at the University of Cincinatti, Ray Tensing. The video is powerful, offering a disturbing look into police brutality in America. Its role is also central in bringing Tensing to justice, as his arrest was paralleled by the prosecutor office’s release of the video. But should you watch the video – one that graphically captures the last minutes of Dubose’s life?

An Answer for Srebrenica

It was rainy and cold in eastern Bosnia, much colder than the previous days spent in Sarajevo. After being bundled into a stuffy bus for a few hours, though, the slight drizzle felt refreshing. We had stopped at a rural gas station for a restroom break, no more than an hour from the border with Serbia. We waited under the pavilion for the bus to depart, passing around a fifty-cent chocolate bar from the store inside. The flavor was thick and sweet, what felt like a much-needed indulgence in preparation for what was to come.

Continue reading “An Answer for Srebrenica”

The Ivy-Wall Street Pipeline

The Ivy League has always been associated with high status. It is the elite of the United States higher education system, boasting some of the most successful graduates in the world. Alumni from schools like Harvard and Yale have gone on to become politicians, doctors, artists and a variety of other accomplished careers. Yet, in recent years, one high-status career path has begun to dominate the graduating classes of the Ivies: the Wall Street analyst.

The Other Side of Antebellum Quaker History

In the basement of my house, the walls are covered with history. Shelves backed against the faux-wood paneled walls are lined with studies on Nixon, several histories on London, biographies on FDR, a history of Soviet Russia, California’s oranges, and an entire row of green cloth books depicting U.S. history from the French wilderness to WWI.

Continue reading “The Other Side of Antebellum Quaker History”

Seeking Out Schrödinger’s Cat

The weather app on my phone isn’t working, though maybe working incorrectly is the best way to put it. By most indications, everything is perfectly normal; backgrounded by a slowly shifting vista of blue-grey clouds, a rounded, minimalistic font reads cloudy and fifty-one degrees. But, if the raindrop impacts on my window are any indication, its prediction is incorrect.

A Pro-Choice Argument for Investigating Planned Parenthood

Long marked by intense and polarizing opinions, the abortion debate has found its latest controversy. The topic in focus? Fetal tissue donation, in which researchers pay abortion providers for tissue samples from aborted fetuses. Two videos, both published by the Center for Medical Progress, an organization backed by pro-life group Live Action, have brought the issue to the forefront of public debate. In the first widely-circulated video, a Planned Parenthood employee discusses prices for fetal tissue samples, in addition to describing the abortion procedure in explicit detail. A second video, also depicting a conversation about buying fetal tissues for research, shows one Planned Parenthood employee joking that she wanted “a Lamborghini” as compensation.

Continue reading “A Pro-Choice Argument for Investigating Planned Parenthood”

Islamophobia and a Shooting in Chattanooga

He had a “Muslim name.” He may have been depressed. Perhaps he was using drugs and alcohol. He visited Jordan in 2014. He had an upcoming court date for a DUI charge. And, above all, he was a Muslim.

Continue reading “Islamophobia and a Shooting in Chattanooga”

Imagining Trinity’s Echoes

It was seventy years ago today that the New Mexico desert was first lit in the glare of a nuclear explosion. Dubbed “Trinity” by the scientists who had built it, the 1945 test was the first time an atomic bomb had ever been detonated. A little over a month later, similar devices would be dropped on the Japanese cities of Nagasaki and Hiroshima, ending WWII in the Pacific and killing as many as 200,000 people. Three explosions in three different locations, they were the first of many, with results that sparked fears of nuclear warfare that remain today. And now, seventy years later, photos depicting the tests pay homage to the dark anniversary.

Remembering the Underground Schools of Kosovo

An abandoned school lies among the neighborhoods dotting the outskirts of Prishtina, Kosovo’s capital city. Forgotten by some and removed from the public eye, the school is unimposing, yet instantly recognizable. Jutting out amongst the winding alleyways, the building’s unmistakeable silhouette rises above the surrounding homes. The home is now abandoned, its fire-blackened walls crumbling into the hallways. There are few indications that it used to be a place of learning; looking from the outside, it appeared to simply be a burned-out shell of a building. Yet the piles of desks and faded chalkboards at the head of several rooms made the building’s former purpose clear.

Continue reading “Remembering the Underground Schools of Kosovo”

Whiteness and Go Set a Watchman

This article has a set of discussion questions tailored for classroom use. Click here to download them. To see a full list of articles with discussion questions and other resources, visit our “Educational Resources” page.

The release of author Harper Lee’s long-awaited second novel, Go Set a Watchman, has sparked controversy even before hitting the shelves. Central among these controversies is the revelation that Watchman’s Atticus Finch, a celebrated character from Lee’s To Kill a Mockingbird, is portrayed as a harsh racist, more akin to the Ku Klux Klan than the defense against racism with which he is associated. As parents reevaluate naming their children after the character and others raise suspicions about the book’s publication, it is practically ensured that the text will be one of the most controversial publications this year. Yet, for others, the publication of Lee’s latest novel has provided the opportunity to air longstanding grievances that existed long before Go Set a Watchman – grievances that stand to change the way we think about To Kill a Mockingbird’s legacy.

Foremost among these criticisms are concerns about both novels’ depiction of racism, especially in light of characters like Atticus Finch. A recent op-ed written by Colin Dayan noted that To Kill a Mockingbird’s plot, traditionally praised as a stand against racism, contains more problematic elements in the way its black characters are presented. In Lee’s novel, Dayan argues, black people are either victims or are simply dragged “humbly in tow” behind white characters like Atticus. Characters like Tom Robinson, he argues, are primarily used to draw attention to the heroism of these white characters – to the point where many of the non-white characters are included “only to be helped or killed by whites.” Others, including acclaimed author Toni Morrison, have also drawn attention to the damaging “white savior” narratives upon which Mockingbird operates, presenting a reading of the work not often considered by white audiences.

While the dehumanized black characters in Mockingbird are certainly a problem, it may not be entirely the fault of the author. After all, Mockingbird is told largely from the perspective of a white child, a move Lee has said is grounded in her own experienced reality. The autobiographical nature of the book means that this white perspective certainly factors in prominently, which could be one reason the book exhibits the trends that Dayan describes. In some ways, then, establishing black characters like Tom Robinson as relatively dehumanized victims could have been central in building the worldview of a young white girl at the time, as Scout Finch is in the book. It could also be argued that the book may not have been as poignant if told from experiences and perspectives unfamiliar to the author. Personal writing is often incredibly powerful, and without its use in Mockingbird, the book may not have risen to prominence in the first place.

Regardless of author’s intent, however, Dayan’s points about the relatively dehumanized black characters still stands. In light of these points, it is necessary that we reconsider Mockingbird’s foundational role in educating about racism. For many students today, especially white students, reading To Kill a Mockingbird may act as a foundational early element of understanding racism. Within this educational process, characters like Atticus are too often held up as heroes, while texts focused on non-white characters fighting racism do not receive nearly the same focus. These trends are not isolated; in an op-ed for The Huffington Post, John Metta writes that discussions about racism in the United States are overwhelmingly considered through the feelings of white people – a trend certainly not helped by the “white savior” narratives like those in Mockingbird.

In this regard, countering the “white savior” narratives in Mockingbird necessitates that students be introduced to more varied representations. An excellent example would be Morrison’s books; works like Beloved and The Bluest Eye offer powerful anti-racist narratives from the experiences of non-white characters. Exposing students to these texts not only diversifies the experiences about which they are reading, but also helps counteract white-focused narratives that hinder discussions about racism. And while the legacy of Go Set a Watchman has not yet been cemented, it has become clear that white-centric accounts of racism like its predecessor can no longer act as the definitive source material on race.

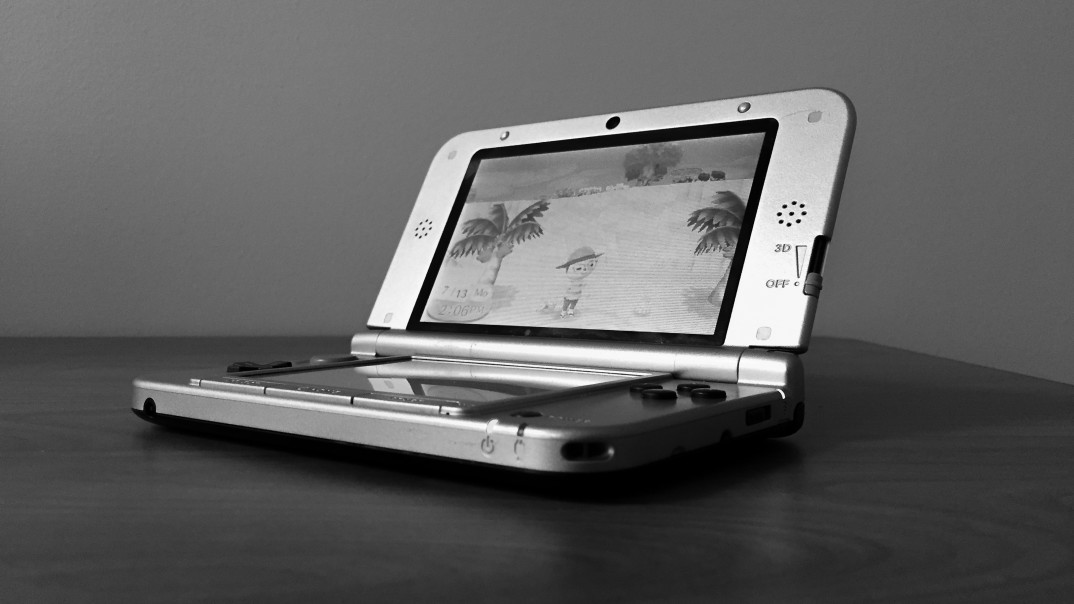

The Imperialism of Animal Crossing

When I first popped the cartridge for Animal Crossing: New Leaf into my Nintendo 3DS, I had no idea I would be playing a game about imperialism. I had played iterations of the cute “life simulator,” complete with its talking animal villagers and customizable houses, since it first came to the United States on the Gamecube in 2001. The colorful art style and simplistic premise of New Leaf checked all the right nostalgia boxes, and I was excited to see what the latest iteration in the series had to offer. Considering imperialistic narratives was hardly the priority.

I Am The Lorax, I Tweet for the Trees

Lovers of social media, rejoice! It appears that even the furthest expanses of nature are not beyond the range of wireless internet. This was only further underscored this morning, when Japanese officials announced that Mount Fuji, the country’s iconic, snow-topped peaked, will be equipped with free Wi-Fi in the near future. Tourists and hikers alike will now be able to post from eight hotspots on the mountain, in a move likely to draw scorn from some environmental purists.

Reclaiming Identity in Srebrenica

Every time I travel outside the U.S., I bring a book of photos back with me. In part, it stems from a need to remember wherever I have been. But it also lends me new artistic perspectives, allowing me to both better my photography and understand how the country’s artists have imagined their surroundings.

What a Flag Has to Do with Justice

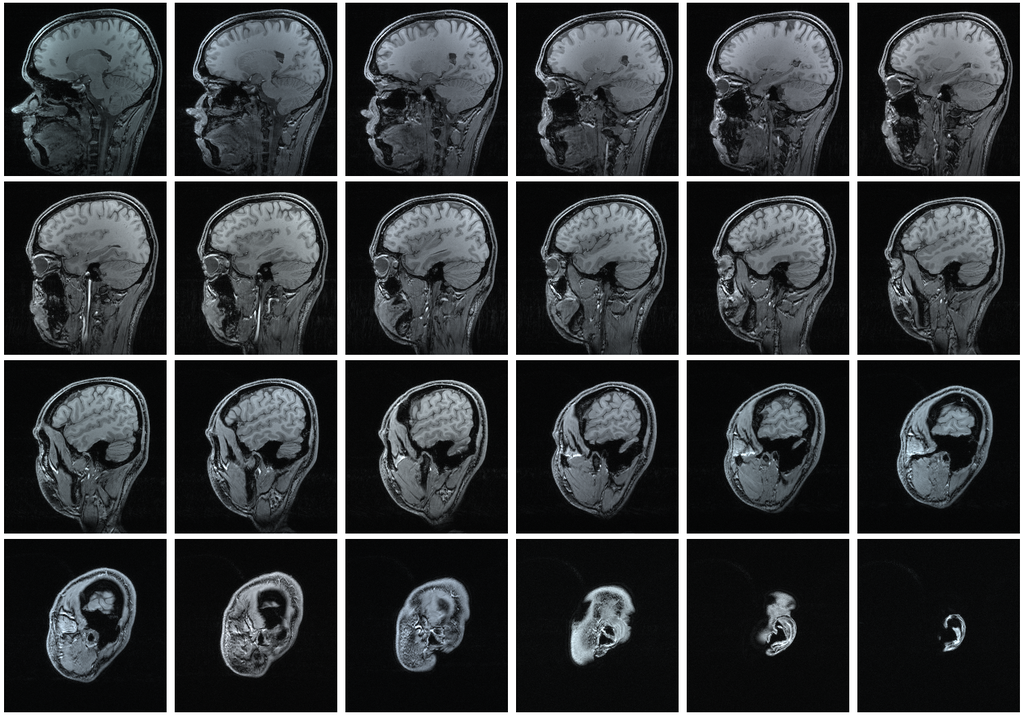

The Over-Treatment Paradox

When it comes to medical care, it would make sense to do as the doctors do. As the foremost experts in their fields, doctors’ choices for their own healthcare may be a good indication of ideal treatment options. However, when it comes to terminal illnesses, for an increasing number of physicians, the answer is nothing at all.

The Threshold for Knowledge

In February, Dr. Michael Hannon presented his talk “The Threshold for Knowledge” as a part of the Young Philosophers Lecture Series hosted by the Prindle Institute and the DePauw Philosophy Department. Check out all of the Young Philosophers Lecture Series videos on our YouTube channel.

Enjoy, and be sure to let us know what you think in the comments!

What We’re Reading, July 3, 2015

Check out these links suggested by members of The Prindle Post staff:

Proud to Be an American (written by a recent DePauw grad!) (Jacquelyn)

Take Down the Confederate Flags, but Not the Monuments (Conner)

Art no one will ever see (Conner)

A Fatal Mix of Heat and Piety (Sandra)

Against Students (Christiane)

Ginsberg’s decision may be the most important one of the term (Andy)

If Mexicans celebrated July 4 like Americans celebrate Cinco de Mayo (Andy)

BP settles 2010 US oil claims for $18.7 billion (Jacquelyn)

What have you been reading lately? Share a link with us in the comments!

A Rose in a City Square

It was Sarajevo that originally brought me to the Western Balkans. A novel about the Bosnian city, of all things. In high school, I had read Steven Galloway’s The Cellist of Sarajevo, the story of four characters living through the four-year siege of the city. It may have been fictional, but Galloway’s retelling left its mark. When I first searched the name of my study abroad program, it was The Cellist that was on my mind. It was The Cellist that informed my decision to sign up, and The Cellist that colored my initial expectations of the region.

The (Long) Road to Equality

As the Supreme Court’s decision is announced in the Obergefell v. Hodges case, one cannot help but reflect upon the shape the discourse has taken, and the possibilities for continuing the conversation about LGBTQ equality. The media coverage has focused on the right to marry, but what about the host of other heretofore denied rights of contract, such as the right to divorce, or the right to form parental agreements? Consider a thought experiment, one similar to the content of some of the testimony heard before the Court:

This thought experiment was a lived reality for individuals across our country, and arose as a result of a patchwork system of recognition. A patchwork system of recognition exists when individual states can choose whether to extend rights to groups that have historically been denied them, and if so, the terms under which such rights will be recognized, enabled, inhibited, or blocked altogether. When a patchwork system of recognition is in place, it can give rise to a number of practical and ethical concerns.

The first challenge that arises from a patchwork system is the clear limitation on one’s freedom of action and freedom of movement that are antithetical to the spirit of a liberal democracy. In this regard, the state has two corresponding duties derived from the general citizen’s freedom of movement: a guarantee that the State will protect the right to travel across city and state lines, and ensuring a citizen’s right to be treated equally to those who are already residing in the area (e.g., not facing unduly burdensome restrictions placed on the right to vote, freedom of expression and association, and that the public acts of one state will be recognized and upheld in other jurisdictions). While this practical constraint is now lifted for those who are married in one state and heretofore unrecognized in others, what of parental agreements and second-parent adoption rules? There are plenty more barriers to full equality and recognition in the contractual agreements that mediate familial life and personal relationships.

The second, more profoundly philosophical, challenge presented by a patchwork system is the effects on one’s personal identity—to what extent can I conceive of myself as autonomous if the state blocks my ability to enter into certain kinds of agreements and be recognized as I wish to be? The state mediates our personal relationships—those between romantic partners and those between citizens and their children, most notably. Insofar as regulatory mechanisms (i.e., contracts or legislation) reflect how individuals see themselves, or at least provide measures to align identity with recognition, this mediation can appear seamless. However, where recognition and uptake fail, the result is narrative friction. My life’s narrative, the self-told story that helps us maintain a sense of who we are over time, becomes interrupted because of state interference. Marital status and parental status, like a person’s sexual identity is a constitutive part of our lives and determines how we constitute many aspects of our practical identities. There are normative expectations and judgments made about one’s behavior, informing how others treat you.

As we move forward, and take up the next battle in the barrier to LGBTQ equality, let us keep in mind that we are legislating people’s lives, their identities, and whether they are recognized throughout the entire country. How does contract law, in itself, dehumanize the texture of human relationships? To what extent should we be mediating our relationships in this way? These questions should be part of the broader conversation concerning the next steps in the long road to equality.

Where Does the Confederate Battle Flag Belong Today?

Political pressure is mounting for the removal of the Confederate battle flag that flies on the state grounds of South Carolina in the wake of the Charleston Church shooting. In recent years, public debate over the flag that symbolizes racism to some and heritage to others has intensified. The divergent views towards the flag inflamed intense public dialogues about racism, culture and history ever since the mid-1950s. Under this circumstance in 1993, United States Senator from Illinois Carol Moseley-Braun claimed “it is a fundamental mistake to believe that one’s own perception of a flag’s meaning is the only legitimate meaning.”

As Moseley-Braun suggested, people should not impose one’s interpretation of the flag to others, and seeking to understand why people are offended by it and why people preserve it are actions that are necessary to take as educated citizens. In order to fully comprehend the implications that the flag gives to a diverse public, understanding the entire history of this symbol would become necessary as people from different backgrounds from a wide range of generations view the flag from a variety of perspectives.

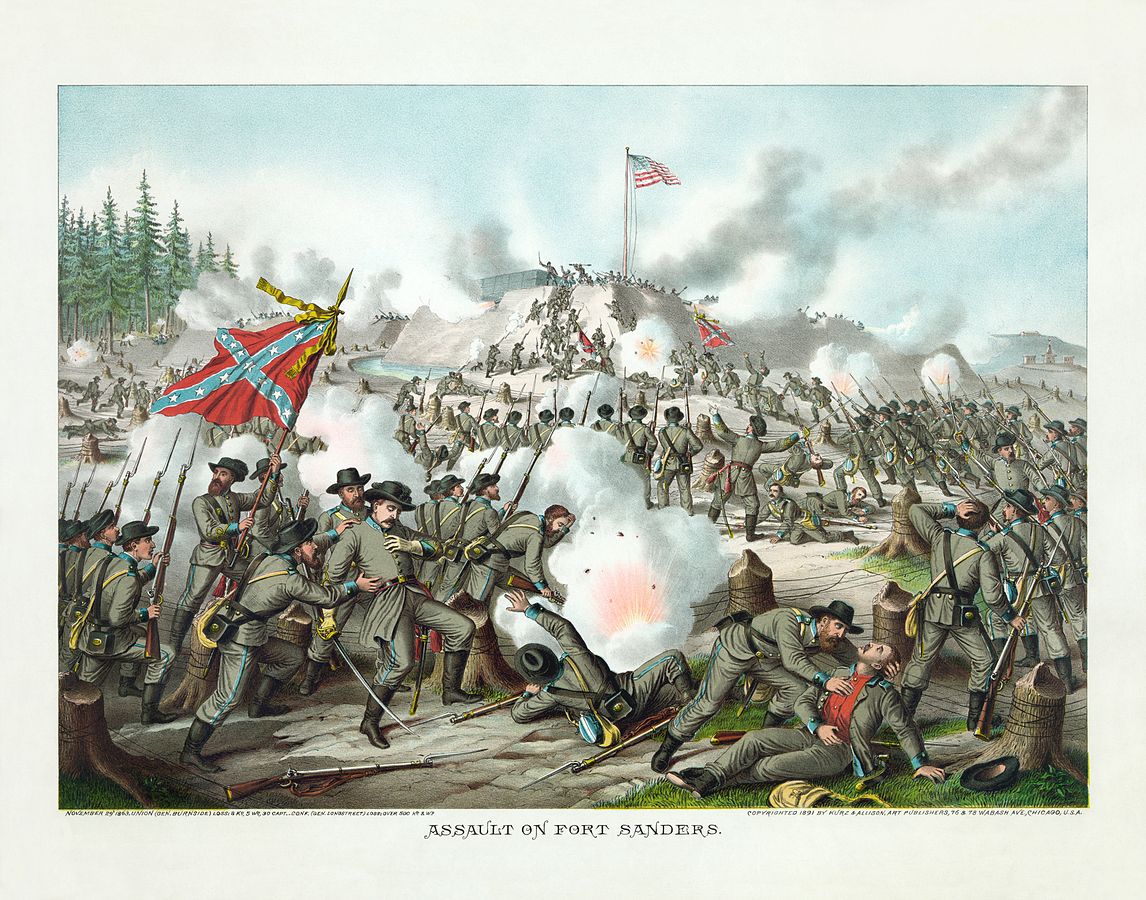

Unlike common belief, during the Civil War the Confederate battle flag did not explicitly symbolize racism nor slavery. Among the southern white population, less than 5% were slave owners, and thus, the majority of the Confederate soldiers did not own slave property. Racism prevailed both in the Union and the Confederacy as both parties did not give African Americans the right to vote and fundamental human rights. In fact, historian James McPherson argues that the main Confederate “cause” of the Civil War was to preserve their country and the legacy of the Founding Fathers, which derived from southern nationalism. As Lincoln recalled in his Second Inaugural Address in 1865, that slavery was “somehow the cause of the war,” the modern debate arguing that the Civil War about slavery, and therefore, the battle flag represents slavery is a mere simplification of history. The war was centralized on the issue on slavery, but one cannot naively generalize that all Confederate soldiers were committed to slavery and supported going to war for that cause.

The history of the flag does not end with the Civil War, but expands after World War II with the rise of the Civil Rights Movement. To many people’s surprise, the proliferation of the Confederate battle flag happened after 1954, when the U.S. Supreme Court declared that racial segregation in public schools was unconstitutional via the Brown v. Board of Education case. Although segregation was illegal, many southern states were reluctant to integrate schools. To show their resistance against integration, the Confederate battle flag came back in the public sphere.

The following year of the Brown case, George Wallace, governor of Alabama, raised the flag as part of his “Segregation Forever” campaign and endorsed it as a symbol of resistance. Not only political figures, but also segregationists brandished the flag to contest integration. It was at this time when the flag entered American popular culture as a symbol of opposition to integration, as Jonathan Daniels, editor of Raleigh News & Observer, lamented in 1965 that the flag had become “just confetti in careless hands.”

So, how should governments, corporations and individual citizens cope with a cultural icon that ignites intense debates? One must acknowledge the difference between public and private display of this flag. Public display of the flag (e.g. on the South Carolina state grounds) should be prohibited with the understanding that this flag symbolizes racism for a wide majority of the public. A governmental institution should not naively display a symbol of racism and show innocence in front of people who are offended by it. One must ask: “what would it be like for a Black citizen living in a state where a symbol of racism waves on the state ground?” Confederate flag images can harass or intimidate citizens and the government must not endorse such figure on its public ground. Moreover, the presence of the flag on the state ground excludes and ignores the population who do not honor it.

On the other hand, it is essential to distinguish between the flag as a memorial and the flag as a symbol of exclusion. The Civil War is undeniably a fundamental part of American history and culture, whose events still fascinate many Americans today. The history of the Confederacy is as valuable as the history of the Union, and no one can erase the four years that the two parties had fought. It is necessary to acknowledge that for many southerners, the Confederacy is part of their family history and the flag is a tool to honor their ancestors. Confederate heritage organizations have the right to privately use this symbol with the understanding that explicit use of the Confederate battle flag may offend others who are uncomfortable with it.

We live in a country where people come from different cultures, nationalities, and family backgrounds, and therefore, it is natural that there is a variety of perspectives on how one considers the Confederate battle flag. Many Confederate descendants look at the flag as a symbol of heritage, but this does not make the flag an honorable icon for everyone. A large number of people view the flag as a symbol of racism, but no one can assume that everyone who raises the flag is a racist. However, a governmental institution must consider the negative implications that this icon gives to the public. Even in private settings, no one can naively use this powerful symbol without considering the message that this flag might give to a wide public. In sum, seeking to understand the diverse meanings of the flag and engaging in honest dialogues would lead us to a better understanding of the proper place of the Confederate battle flag in modern day society.

References

Edward Pessen, “How Different from Each Other Were the Antebellum North and South?” American Historical Review 85 (1980): 1119-49.

James M. McPherson, For Cause and Comrades: Why Men Fought in the Civil War (New York: Oxford University Press, 1997).

John M. Coski, The Confederate Battle Flag: America’s Most Embattled Emblem (Cambridge, MA : Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2005).