The Other Side of Antebellum Quaker History

In the basement of my house, the walls are covered with history. Shelves backed against the faux-wood paneled walls are lined with studies on Nixon, several histories on London, biographies on FDR, a history of Soviet Russia, California’s oranges, and an entire row of green cloth books depicting U.S. history from the French wilderness to WWI.

When I was younger, my sister and I would play in this basement. History books would fly off the shelves and become fairy tales, magic books, prized possessions, all based on their covers. We paid no attention to the actual content of the books. We couldn’t even read the titles. But it made history a familiar playground and fostered a desire in me to understand the past.

I study history, and I love it. Yet now I’ve learned that history is more than a pretty cover and fancy script title; it’s a complex series of events and ideas as interpreted by people at a later date, and we must be careful with how it’s approached.

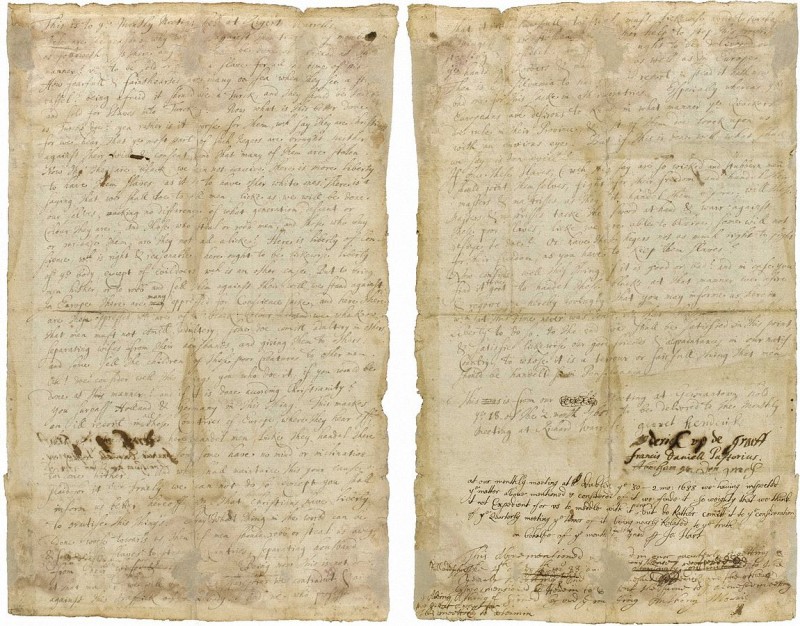

When I started writing my paper on Indiana Quakers in the antebellum period, I wanted to tell the story of a faith so powerful people risked their lives to end slavery. Turns out, that’s not the story the Quakers had to tell. I had to listen to the letters and meeting minutes telling me otherwise adjust my theory accordingly. I had to give them a chance to blow off their dusty covers and open the pages on a new tale.

In 1842, Newport, Indiana was a small Quaker community just north of Richmond and a bustling stop on the Underground Railroad. At the center was Levi Coffin, North Carolina transplant and abolitionist. Coffin unabashedly sent fugitive slaves north until they reached Canada, land of the free. Newport supplied Coffin with food, clothes, and support in order for him to successfully send slaves north. A few residents even housed slaves, risking repercussions from slave catchers.

And yet, in 1842, Newport residents and other likeminded Indiana Quakers found themselves separated from the Indiana Yearly Meeting, the governing body of all Quakers in the state, for being too extreme. Coffin and other abolitionists began meeting in Quaker meetinghouses and discussing integrating free blacks into society, relating their ideals and actions back to the teachings of the Society of Friends.

This alarmed the Yearly Meeting. It was one thing to forgo slaveholding yourself and despise slavery internally. It was another to be an abolitionist and attempt to take action steps to end slavery and help. Abolitionism was incredibly unpopular in antebellum America, including Indiana. Continue to allow abolitionist activities, and the Friends marked themselves as abolitionist supporters. They would have begun to experience firsthand the anger from slaveholders and the majority of Americans who did not want an integrated society.

As a result, the Yearly Meeting had to expel prominent abolitionists from the faith. The majority of Indiana Quakers decided being anti-slavery did not mean they needed to be abolitionists, leaving Newport and Coffin cut-off from their fellow Quakers.

This is not the story we’re told in fourth grade Indiana history. This is not the story told in college Civil War history classes across the state. Quakers were the good guys amidst a bunch of bad guys. They were against slavery when the rest of the country was for it.

The funny thing about history is it’s never that black and white. We want so desperately to think that the abolition movement was a powerful force in the nation and that countless Americans were against enslavement of other humans. It is incredibly difficult for many modern Americans to understand what it would be like to protest a lucrative and highly popular industry boldly when those who did were punished.

Realizing how small and hated the abolition movement was in antebellum America was depressing. Suddenly, those history books become a bit less magical. We like to think that if we were in that situation, we would have stuck to our morals. Yet the Indiana Yearly Meeting of 1842 shows how it can be almost impossible to overcome societal norms and expectations, even in the name of living your values.

We need to study history in order to understand ourselves and where we come from. By looking at Indiana’s 1842 Quaker community, it became so clear how we fall into the formula society writes for us and allow it to take control. It’s easy to judge others for not standing up for their beliefs in order to challenge an unethical situation. It’s much harder to step back and consider all sides to the story, and the lessons that have shaped us into the society we are today.