Reclaiming Identity in Srebrenica

Every time I travel outside the U.S., I bring a book of photos back with me. In part, it stems from a need to remember wherever I have been. But it also lends me new artistic perspectives, allowing me to both better my photography and understand how the country’s artists have imagined their surroundings.

It was this impulse that brought me into a quiet Sarajevo bookstore on my last day in the city. Browsing through the shelves of the photo section, I tried to seek out works by Bosnian photographers that went beyond the simple, tourist-focused representations of the country. After a few minutes, one caught my eye; nestled between piles of photojournalist accounts and tourist books filled with flowery landscapes was a simply bound, small white book. The unassuming cover displayed a single photo: a yellow plastic heart on a background of brushed metal. It was Ziyah Gafic’s Quest for Identity, a photographic record of personal possessions recovered from the victims of the Srebrenica genocide. Both artistically and thematically, it was exactly what I was looking for.

I had not yet visited the memorial to the genocide. On our way back to Belgrade, we were scheduled to make a stop in the cemetery complex outside of Potocari. At the time, I was not sure how occupying such a space would feel. I did not know how I would react when confronted with such trauma, how it would feel to stand in a place that once housed such terrible violence. Part of me, I think, hoped that Gafic’s work could help act as preparation.

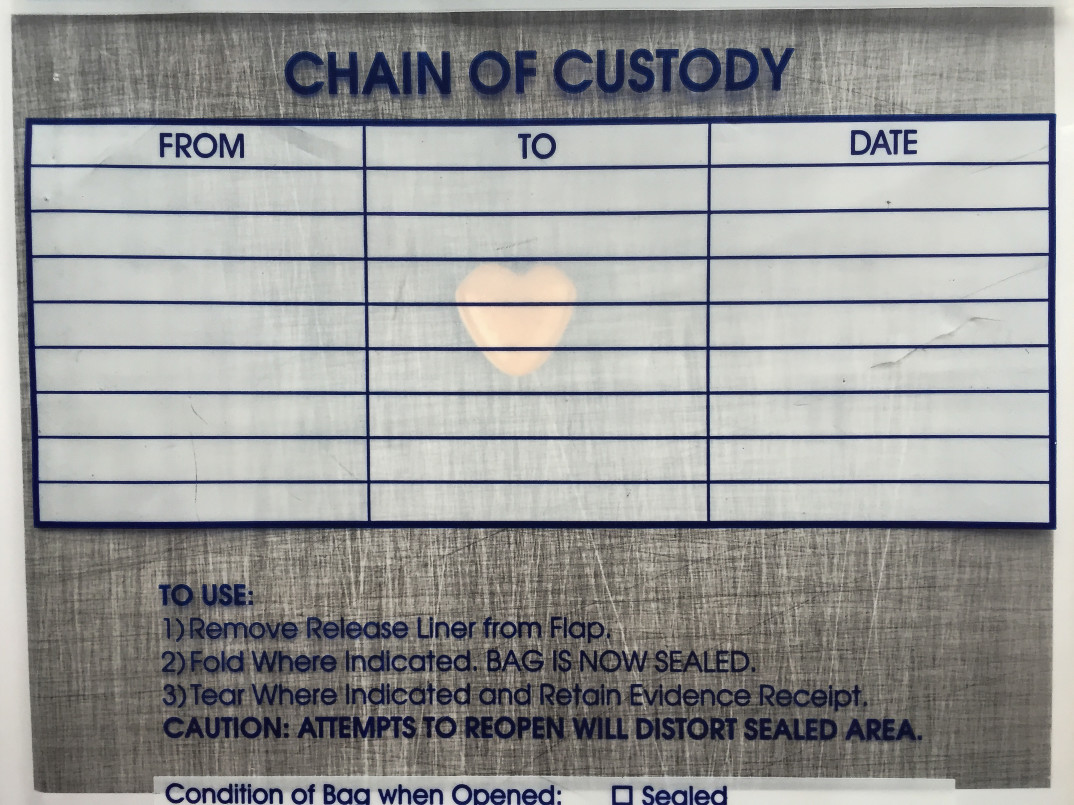

I brought the display copy up to the front desk, and the shop’s owner handed me my purchase wrapped in a weighty plastic bag. Through the translucent cover, I could still see the yellow, heart-shaped button that had drawn me to the book. But now it was obscured by a blank “chain of custody” label, the book’s pointy edges wreathed in thick plastic. It was sealed inside a heavy-duty evidence bag – a bag just like those used to catalogue the objects contained within the book’s pages.

Opening the bag, the printed instructions warned me, could not be reversed. It could not be resealed once one had opened it, the gummy red adhesive at the opening permanently damaged. The mere process of opening the book’s pages, a seemingly inconsequential process, became a deliberate and irreversible act.

The process required to open the book reflected the importance of its contents. For the objects depicted within were not just watches and toothbrushes; they carried with them traces of thousands of human beings. In their campaign to ethnically cleanse Bosnia of its ethnic Muslim population, the Bosnian Serb army had tried to obliterate such traces. They destroyed and altered the landscape, dynamiting mosques and razing the homes of Bosniaks in a vast campaign of ethnic cleansing. In Sarajevo, they tried to reshape history itself by setting Bosnia’s national library ablaze with incendiary shells precisely fired through its glass roof. And in dozens of villages like Srebrenica, they raped and massacred thousands of ethnic Muslims, a sick attempt to erase them from a distorted vision of a Serbian utopia.

Yet these traces still remain. They exist in photographs like Gafic’s, chronicling the legacies some endeavored to erase by unimaginable violence. Vulnerable yet enduring, these traces demanded immense care. They could not be passively thumbed through while browsing a bookstore or glanced over while sitting in a living room for coffee. No, opening this book, and viewing the tragic contents within, could never be a careless act.

As I slit the top of the bag with my keys, the intention of the process continued to occupy my thoughts. I almost felt guilty as I pulled the book from its wrapping, wondering why I had ever done so. Did my interest stem from a genuine care for the owners of these recovered items? Or was it some perverse, morbid curiosity that led me to pull it off the shelf? Perhaps it was a bit of both.

In opening the bag, it was clear that I had become more than an observer. I too was an actor in this sad, 20-year story. I had engaged with these memories and the people to whom they were connected. I could not back away from this engagement, just as I could not reseal that book and walk away from it as if nothing had happened. Though it felt insignificant, I had left my mark here, and I could not deny the responsibility that came with it.

Examining the objects themselves feels clinical, in a way. Each is backgrounded by the scratched metal of a medical table in an unknown examination room, every object lit identically by bright floodlights. In some photos, you can almost see the blurred reflection of the photographer in the brushed metal, haloing the objects in a shadowy pink-grey glow.

But it is here that minute differences resonate the most. Orderly rows of toothbrushes vary slightly in color and design, one ominously coated with the dirt from a mass grave. Rusted house keys lay flat on the table, each attached to a unique string or brightly-colored plastic keychain. Dull silver wristwatches form a tragic mosaic, each dirtied face slightly different from the next.

Trying to comprehend who the owners of these objects were feels like an unfathomable task. In some ways the possessions seem anonymous, their identities obscured by the sheer volume contained within the book. So little can be learned about someone from the color of pocket comb he carried, or whether he wore metal- or plastic-framed glasses. Even the mud-stained Polaroids and identity documents seem to fade together, an overwhelming sense of loss obscuring the uniqueness of each object.

Yet Gafic’s photos demand that we counter this homogenizing sense of tragedy. They demand that we see these objects both distinctly and in context, humanizing their owners in a way unmatched by post-war statistics or governmental reports. It is difficult to imagine the enormity of 8,372, the current count of men and boys killed at Srebrenica. Yet these objects tether each statistic to a human being tragically lost to genocidal hate. It is their identities that must be remembered.

This Saturday, officials and victims’ families will once again convene in the quiet cemetery outside Potocari. There they will lay to rest 136 victims whose bodies have been identified in the last year, and mark the two decades that have passed since the genocide. Speeches will be made by politicians from around the world, denouncing the killings and recognizing the wounds that twenty years have not yet healed. Some may express wishes to undo the past, to erase the broken seal that unleashed this terrible atrocity upon the people of Srebrenica. Others may refuse to recognize the full extent of the genocide, or to try and obscure their involvement in its tragic legacy.

It is among these commemorations that the identities of Srebrenica’s victims can never be forgotten. These identities are vulnerable, contained in plastic toothbrushes or rusted pocket watches. Yet preserving them, and remembering the unique individuals to whom they once belonged, defies the genocidal forces that led the Bosnian Serb army to try and erase them in the first place.

As Gafic’s title suggests, this endeavor is not easy. It is a quest, one hard-fought and, at times, overwhelming for the survivors involved. But it is one that those left in the genocide’s wake continue to face, even twenty years later. Acknowledging our own duty to responsibly aid in this quest, and the many like it from wherever genocide leaves its mark, is of utmost importance.