Man v. Machine: The Ethics of AI Art

The creation of digital art is nothing new, but advances in artificial intelligence have created a novel environment where all sorts of media can now be created without much human input. When Jason M. Allen won the Colorado State Fair for his piece “Théâtre d’Opéra Spatial” it sparked fierce debate about the nature of art and the merits of AI creations. But we should be careful not to confuse the many ethical issues involved. Is the outcry about the fairness of contests or about the future of art?

Allen, a video game designer, created his entry using an AI called Midjourney. It works by creating images from textual descriptions. Allen claims that he created hundreds of images before selecting only three. He then made some additional adjustments using Photoshop and boosted their resolution with a tool called Gigapixel. He entered the Colorado State Fair under the digital arts category which is defined as “artistic practice that uses digital technology as part of the creative or presentation process.” Allen claims that he informed the competition that the image was created with AI. The competition’s judges, meanwhile, say that they were not aware. Nevertheless, they said they would still have given it first place based on the piece itself.

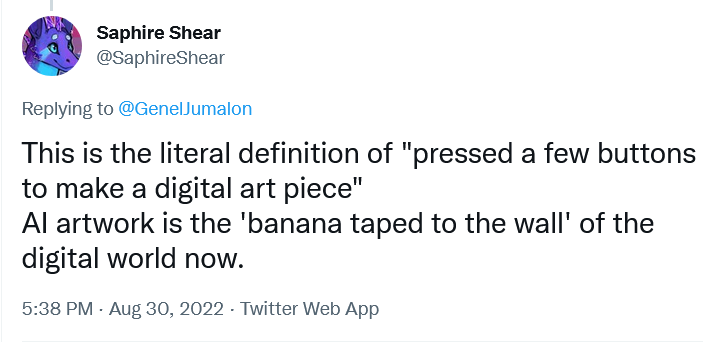

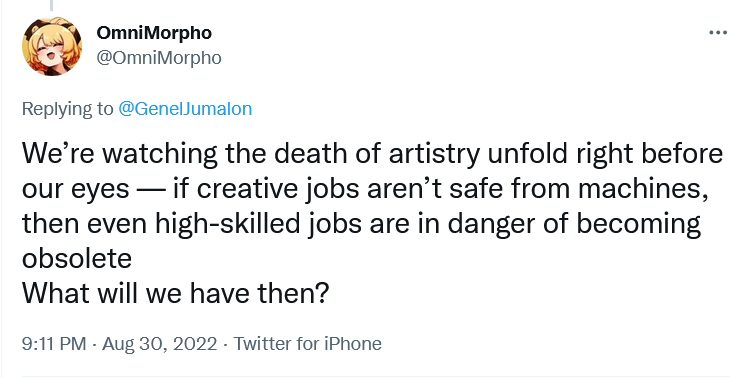

Online reaction was harsh.

While the uproar isn’t surprising, it’s not clear that everyone has the same objections for the same reasons.

Let’s address the first major ethical question which centers around the contest: Was it wrong of Allen to submit the AI created work and be awarded the blue ribbon over other artists who created their works by hand? The contest’s definition of digital arts was sufficiently broad enough that AI created works were eligible. The work was entered using the name “Jason M. Allen via Midjourney.” Also, according to Allen, this was not simply a case of a few button presses, but 80 hours of work – tweaking the prompts to get the image he wanted and making a selection out of 900 iterations. While Allen spent his time differently than the other artists, this doesn’t mean that creating the image lacked skill, effort, or the aesthetic taste.

On the other hand, others might object that it was wrong for Allen to enter the contest since he was not the artist; it was the artificial intelligence who actually created the piece of art. Did the AI create the work, or is the AI merely a tool for Allen – the true creator – to manipulate?

The judges selected this particular work because of the impact it had on them, and Allen was deliberately attempting to tie together the themes that the painting conveys. The AI, meanwhile, has no notion of the impact that imagery might have; it doesn’t think any differently about the art conveyed by painting 899 or 900.

To further complicate things, the AI’s creation is based on training data from other artists, raising the issue of plagiarism. While the AI piece is not a direct copy, it does take “inspiration” from the art it was trained with. Often art is about meshing together styles and techniques to create something new, so it is difficult to view this purely as copying other artists. If the piece is not a copy of other artists, and if the AI is not the artist, then it stands to reason that Allen is the artist. If not, then this would be a piece of art without an artist, to which many might say that it therefore is not a piece of art at all and thus should not be allowed entry in the contest.

Answering the question “what is art?” might tell us if AI can actually create such a thing, but such a definition is hard to pin down and it’s easy to rely on preconceived notions. Generally, art follows certain aesthetic patterns and conveys content that people find meaningful. The judges awarded the prize based on the spirit it invoked. We can’t unpack such a complicated question here, but we should ask whether this understanding of the creative process truly threatens art. Was Allen right to declare that “Art is dead Dude”? Is there any role left for artists?

When the camera was first developed, people said that it would mean the end of the painter, but obviously painters still exist today. Ultimately, the human artist brings a kind of authenticity and uniqueness to the work.

AI doesn’t replace aesthetic choice and esthetic judgment since at the end of the day, it is we who must decide if anything produced has merit. While the role of the artist may be changing, their place in whatever system that produces such works remains paramount.

A final ethical issue is the question of the future of the artist in general. Even if we accept that Allen did nothing wrong, many still decry the end of the professional artist. As digital artist RJ Palmer claims, “This thing wants our jobs, it’s actively anti-artist.” Even if we accept that Allen’s work itself isn’t plagiarism, there is no denying that AI produced images only work by being trained on the work of real artists, which the algorithm can then borrow any stylistic elements it wants. This has the potential to create an intellectual property nightmare since smaller artist won’t be able to profit from their work to nearly the same degree as a company using AI, which will produce images in the style of that artist at a far faster pace. Federal courts are now hearing a case over whether the U.S. Copyright Office was wrong to reject a copyright for an AI-made piece.

Of course the application of AI to a given field and the threat that it creates to the workforce is not confined to the world of art. Eventually there may be legal and industry reform that can mitigate some of these issues, but many artists will no doubt suffer and it could undercut the art industry as whole. As one artist notes, it isn’t so much that AI can create something, but that it will always be a kind of “derivative, generated goo.” Clearly, the implications of Allen’s win run deeper than a single blue ribbon.