The Imperialism of Animal Crossing

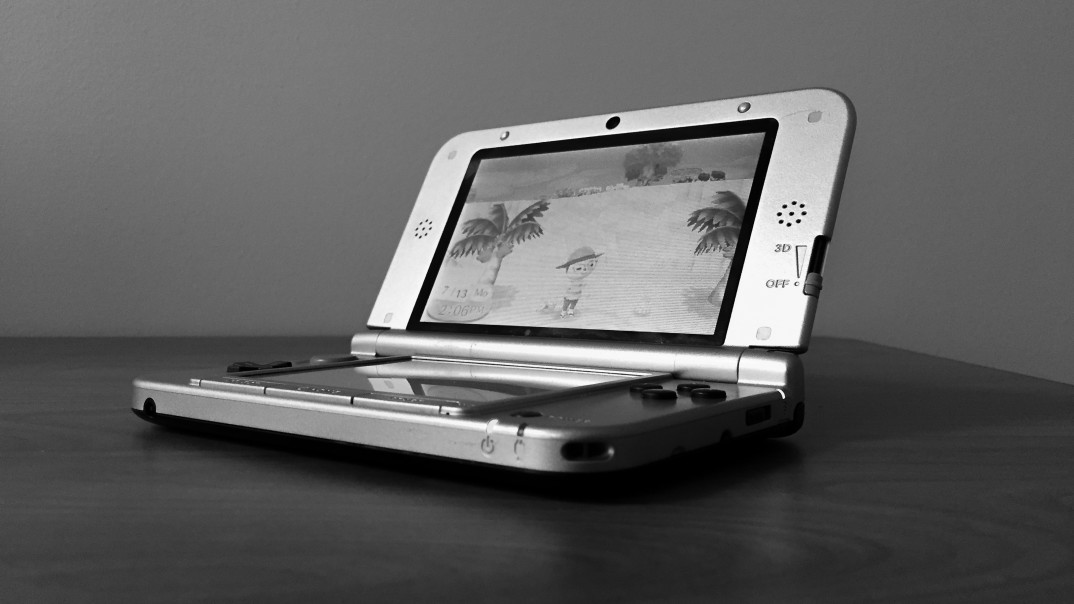

When I first popped the cartridge for Animal Crossing: New Leaf into my Nintendo 3DS, I had no idea I would be playing a game about imperialism. I had played iterations of the cute “life simulator,” complete with its talking animal villagers and customizable houses, since it first came to the United States on the Gamecube in 2001. The colorful art style and simplistic premise of New Leaf checked all the right nostalgia boxes, and I was excited to see what the latest iteration in the series had to offer. Considering imperialistic narratives was hardly the priority.

Despite its relaxed atmosphere, New Leaf takes its economy quite seriously. From the very beginning, your character is indebted to Tom Nook, a raccoon-turned-realtor who sells you your house. Many of the upgrades he and other shops offer require sums of hundreds of thousands of Bells, the game’s currency (for reference, a t-shirt costs between 350 and 500 Bells in-game). Want to install a stone bridge so you can cross the river? That’ll be 128,000 Bells. A windmill overlooking your town’s beach? 372,000. A complete set of rare furniture for your bedroom? As much as 2.5 million. This doesn’t even include the price for paying off your mortgage (yes, in this game, you do pay off your mortgage), which can set you back by nearly 7.6 million. When making 40,000 Bells in a day requires a fair degree of dedication, such prices seem particularly daunting.

Enter the tropical island. After making your first house payment (39,800 Bells), the game grants access to a motorboat that can take you to the small island. The fee for each trip is 1,000 Bells, but the rewards are extreme; the island is full of rare and valuable bugs and fish, some of which sell for up to 15,000 Bells each. Bringing back a chestful of the rarest wildlife can net as much as 600,000 Bells per trip. Once you invest your earnings in the game’s turnip-based “Stalk Market” back home, these profits can easily reach into the tens of millions.

On the surface, such elements seem problematic. There are few circumstances in which plundering indigenous lands for their natural resources, by a white character no less, could be considered ethical. Yet the game is explicitly designed to incentivize this apparent exploitation. The island features prominently in many of the game’s advertisements and trailers. Additionally, while previewing the game, Nintendo of America’s President and CEO personally encouraged new players to visit the island. It is not poor advice; in many ways, taking advantage of the island’s resources is the most viable means of paying off your debts. But something about the entire transaction still feels wrong.

Yet the villagers on the island are happy. In fact, they encourage you to come back and revisit their souvenir store frequently. Entirely absent are any suggestions that your actions are damaging to them or their home. Nor do your actions foster negative environmental repercussions; regardless of how many sharks you pull from the ocean or beetles you tear from the trees, more will always appear. There are consequences if such actions are taken too far; uprooting the inland trees and shrubs to increase beetle spawn chances will drive off some species entirely. But, barring any drastic restructuring of the island, the relationship appears to be mutualistic.

In this regard, playing into New Leaf’s imperialistic themes may not be an unethical choice. Despite their real-world implications, within the world of New Leaf, most of your actions carry no negative consequences. Short of decimating the island’s ecosystem through drastic measures, the environment never suffers from your actions. Nor do the villagers on the island, at least within the game’s context. In some ways, they cannot suffer at all, at least not in the real-world sense. The case might be different if the villagers were controlled by other players. However, like the non-playable characters in other video games, the island’s villagers are simply lines of code, with no living being connected to them. With no real-world or in-game negative repercussions, then, classifying the action as unethical seems inaccurate.

If the actions taken on New Leaf’s tropical island are not unethical in themselves, can they really be called exploitative? Perhaps not, although the narratives they employ do merit scrutiny. Within the game’s world, there is no resource scarcity or neocolonialism – only artificial villagers and the player coexisting in some sort of tropical paradise. Yet the same cannot be said for the real-world parallel of these narratives, where imperialism has plundered ecosystems and fractured indigenous communities. This context must be considered, especially when it is being used (albeit free of negative consequences) for an entertaining purpose.

Given the game’s younger target audience, maintaining an awareness of these problematic narratives is especially important. The effects may be difficult to detect, but exposing a child to such narratives could potentially contribute to a foundation of their worldview later in life. Similar concerns have been raised about shows like Thomas the Tank Engine, which has sparked debate about what some argue is a problematic vision of “robber baron” capitalism. Children’s media are hardly immune to potentially damaging or insensitive narratives like this, and being aware of how they inform the audience is a critical element to approaching such media.

While the choice to “exploit” the island does not seem to be an unethical one, there is something to be said for the “ethical choice.” In fact, the game itself may be about making the choice to forego the island’s get-rich-quick allure in the first place. New Leaf feels designed to be played in short, daily increments, with most tasks taking a few days to complete. Reviewers have argued that this is precisely the point of the game – to be constantly anticipating tomorrow, rather than completing all of your goals today. Amassing wealth without the island takes time, spread out to allow the player to take in the virtual world’s nuances and enjoy the slow progression of the game. In this regard, making the “ethical” choice is also one in accordance with New Leaf’s larger structural vision.

Problematic narratives aside, I plan to keep playing Animal Crossing: New Leaf. The game is a great way to relax and, as others have noted, is notoriously addictive. At this point, the “see you soon” message that appears on the save screen seems more of a self-aware guarantee than anything. So I shall return. I’ll continue to pay off my debt, reorganize my house, meet up with friends, and even visit the island from time to time. I shall do so with an awareness that my actions in-game bear little relevance to the real world, but that they can also fall into problematic and destructive narratives. And when I next visit the island, maybe I’ll leave a few beetles on the trees or sell fish to the shop owner’s daughter instead. It may be an ultimately meaningless gesture, and one that would lose me a bit of money in-game. But it is a satisfying one, just the same.