As I glance over the front page (or, let’s be real, the home page) of various newspapers, nearly every story is about either COVID-19 or U.S. racial injustice. Here I want to pause and look not at the stories themselves, but at the discourse developing around both stories. I want to look at the moral outrage we feel when others suggest imponderable comparisons. Consider two personal examples.

I was outraged at Lt. Governor Dan Patrick’s suggestion that we should restart our economy even though it increases the chance that our grandparents might die from COVID-19. I was appalled that anyone would compare the merely economic harm of shutdowns to the incalculable and irreplaceable loss of human lives. I felt a similar outrage at people bemoaning the damage done by the looting which followed the murder of George Floyd. I was appalled that anyone would compare the merely economic harm of looting to the inexcusable and incalculable evil of racialized violence in the criminal justice system.

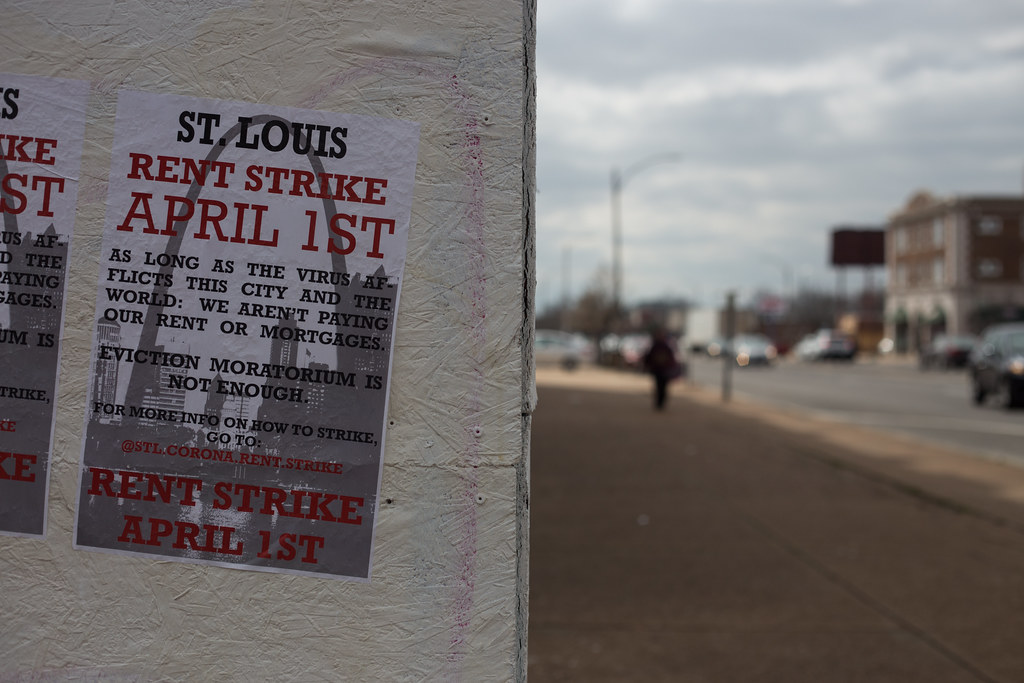

It is this outrage that I want to pause and consider because, while I believe the outrage is appropriate, I worry about the effects of rendering certain comparisons imponderable. In ordinary times I would be horrified by the harm done by a global recession. In ordinary times I would happily condemn looting that exasperates inner city food deserts or harms locally owned businesses. Yet, in this context, not only am I not worried about these harms, but I find myself incensed at those who talk about these harms too openly. Do they not realize how insignificant those concerns are given what else is as stake? Do they not realize how talking about property damage trivializes the continuous damage visited on minority communities?

Fortunately, there has been excellent research on the outrage we feel when people consider certain trade-offs. This outrage arises when we see others trading off what the social scientist Phillip Tetlock calls ‘sacred’ values for ‘secular’ ones.

To take a commonly cited example, if you present people with a story in which a hospital administrator faces a choice between saving the life of a boy and saving the hospital a million dollars, people won’t just condemn the administrator who chooses the money, they are willing to punish an administrator who even lingered over the question before eventually choosing the child. We are not just upset with those who make the wrong trade, we are outraged with those who even ponder the trade-off we consider taboo. This is true even though a hospital that routinely sacrificed a million dollars anytime it could use that money to save a life would not remain solvent for long.

So why do I find certain trade-offs outrageous. My mind codes the economic liberties of Dan Patrick’s “American way of life” as a merely secular value, not to be compared with the sacred lives of my grandparents. But of course, to many more patriotically inclined citizens, our economic way of life is absolutely a sacred value, and thus something that might sometimes require tragic trade-offs (a ‘tragic trade-off’ is one where we must sacrifice one sacred value for another; a ‘routine trade-off’ is one where we sacrifice one secular value for another).

Once we understand the psychological underpinnings of our moral emotions, those emotions begin to flounder. As I study moral outrage, I learn that what we consider sacred depends, in part, on the peculiarities of how something is presented. Is life insurance a way to bet on a loved one’s death, or a way to secure the financial security of one’s children? Does social security reform break faith with senior citizens, or technically rework bureaucratic infrastructure? A large portion of politics is reframing taboo trade-offs into routine or tragic ones.

By default, I treat life as a sacred value. But if you want to change how I code it, just point out that every year half a million people die of malaria (and well over one million people from Tuberculosis) and yet I’m not constantly outraged that trillions are not being siphoned from the global economy to malaria eradication. I’m unwilling to admit to myself that I care more about diseases that threaten U.S. lives, and thus, to avoid moral hypocrisy, will swiftly ‘mentally recode’ the millions of deaths caused by preventable disease from a moral atrocity to a routine statistical artifact of a large global population.

Similarly, by default, I’m appalled at the thought that we would send U.S. factory workers back to work where they risk contracting COVID-19 just to jumpstart global supply chains. But if you want to change how I code it, just point me towards the UN University’s recent working paper suggesting the disruption of global supply chains runs the risk of plummeting half a billion people back into poverty and undoing a decade of progress toward the UN’s development goal of ending poverty by the year 2030.

Indeed, present me with both of these arguments and suddenly I feel outraged that my fellow U.S. citizens, who are shielded from the worst economic impacts by stimulus checks and a comparatively excellent public health infrastructure, are willing to cripple the economic foundations of the developing world just to avoid a statistically small risk of death.

As Phillip Tetlock puts it, the “boundaries of the thinkable ebb and flow as political partisans fend off charges of taboo trade-offs and fire them back at rivals.” So what role should these ‘imponderables’ play in my politics? Are they a recognition of incalculable human dignity, or a tool of self-deception by which I write off the legitimate worries of those of different political persuasions while indulging in the personal catharsis of moral outrage?

Should I do away with my imponderables? According to many great ethicists, the answer is: No. The great Catholic philosopher Elizabeth Anscombe famously said she was uninterested in arguing with anyone who thought it was an open question whether “procuring the judicial execution of the innocent” could be justified, because such people “show a corrupt mind.” Raimond Gaita, emeritus professor of moral philosophy at King’s College London, agrees with Anscombe and argues that even to see certain courses of action as possible, or certain trade-offs as legitimate, is already to have exhibited a deep moral failing.

To these philosophers, moral imponderables are not a mere peculiarity of moral psychology. Rather, they are essential to a healthy moral sensibility. What it is to have a proper regard for justice is to demand justice be done, whatever the economic costs may be. Why? Because humans have something like a sacred value, or an inner dignity, which dictates that justice take precedence even over the social good.

Why is it appropriate to feel outrage when people bring up the injustices done by looting during a national conversation on racial violence? It is not because the injustices of property damage don’t matter, nor because such injustices are less important (though of course they are). Rather, it is because to recognize the dignity of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, or Ahmaud Arbery is to recognize that the tragedy of their death is, in a very real sense, incomparable to any other injustice. To bring up other injustices in comparison is already to have missed the incalculable dignity of a human being.

Of course, many disagree with Anscombe and Gaita’s claim that moral sensibility involves a recognition of certain imponderables. Consider this vision of intellectual life offered by Simone Weil:

“The degree of intellectual honesty which is obligatory for me, by reason of my particular vocation, demands that my thought should be indifferent to all ideas without exception – it must be equally welcoming and equally reserved with regard to everyone of them. Water is indifferent in this way to the objects which fall into it. It does not weigh them; it is they which weigh themselves, after a certain time of oscillation.”

It is a beautiful picture of unwavering commitment to honest investigation. Yet, for all its beauty, the position seems contradictory. The thought seems to be that the value of truth is so great that one should be able to ask any question and consider any thought, no matter how vile, if it can help one reach the truth. But note what has happened. We’ve rejected all sacred values, made everything thinkable, because of our commitment to the final sanctity of truth. Weil has made it thinkable to transgress any sacred value, but only for the sake of her own sacred value which she privileges above all others.

We cannot escape sacred values. Of course, it is also difficult to put a recognition of sacred value into practice. It sounds nice to say the value of justice is incalculable, but we cannot spend billions on every trial to make absolutely certain that justice is done. The painful reality is that there is only so much we can spend on any given life. Some trade-offs must sometimes be made.

So, what can we conclude about the politics of the imponderables?

I simply want to urge caution. First, to urge caution when we are tempted to quickly condemn others for making comparisons we find inhumane. When we recognize how fickle our own outrage can be, it should encourage humility and self-reflection. We must remember how our own mental biases might distort what we are willing to consider, and thus might seal ourselves off from insight.

However, we also need to be cautious of the opposite temptation. There is a certain seductive temptation in being willing to trade off certain values. There is a “titillation” in thinking “dangerous thoughts.” We love to congratulate ourselves on being brave enough to think the thoughts others refuse to face. We get to feel smugly superior to everyone else who remains unable to remove their moral blinders. But this too is a dangerous and distorting temptation, and it’s a temptation that compromises our ability to appreciate the sacred.