“…we haven’t apologised for the event itself, per se, but apologised for the distress the event caused.” – Chris Salisbury, Rio Tinto Iron Ore CEO

In late May, mining giant Rio Tinto shocked Australia, and the world, by blasting an ancient and sacred Aboriginal site to expand an iron ore mine.

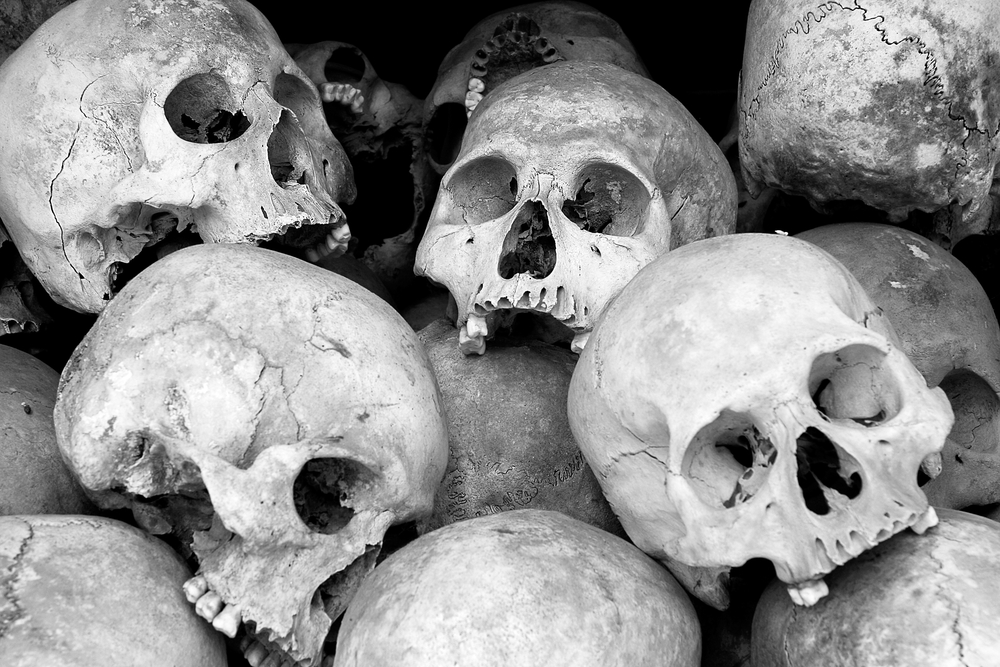

The blast destroyed a cave in the Juukan Gorge, located in the Hammersley Ranges in Northern Western Australia, that was one of the oldest of its kind in the Western Pilbara region, and was the only known inland site on the entire Australian continent to show signs of continual occupation through the last ice age (between 23,000 and 19,000 years ago) during which, evidence suggests, most of inland Australia was abandoned as the continent dried out and water sources disappeared. The cave site itself was found to be around 46,000 years old.

The blast received ministerial approval in 2013, consent obtained under Western Australia’s out-dated heritage laws drafted in 1972 to favor mining interests. Following the 2013 approval, archaeological work carried out at the site discovered it to be much older than originally thought, and to be rich with artefacts and sacred objects.

The 1972 Heritage Act does not allow for renegotiation of approvals based on new information; however, the act is due to be replaced by new legislation, and various factors have caused the renewed heritage act to be delayed. The new draft bill currently in preparation includes a process of review based on new information. In its response to the new draft legislation Rio Tinto has submitted a request that consent orders granted under the current system should be carried over.

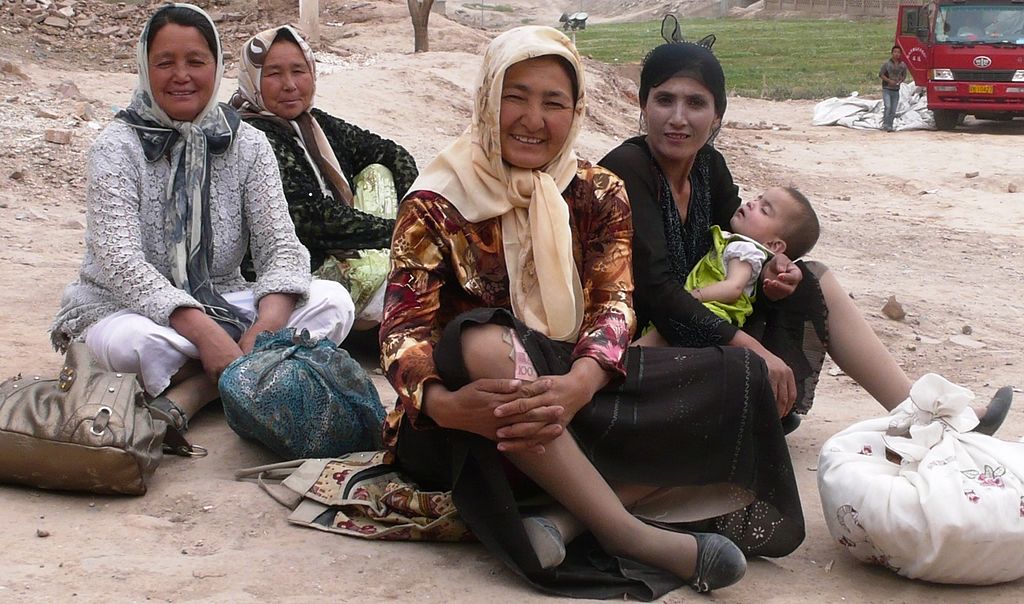

The blasting of the site was conducted without prior notification to traditional Indigenous owners, or the state government, and has caused deep distress to the Puutu Kunti Kurrama and Pinikura people (PKKP). Among some of the precious and rare items recovered from the site prior to the blast was a 4000-year-old plaited length of human hair from several people which DNA testing revealed to belong to the direct ancestors of the living PKKP people.

“It’s one of the most sacred sites in the Pilbara region … we wanted to have that area protected,” PKKP director Burchell Hayes told Guardian Australia.

Peter Stone, Unesco’s Chair in Cultural Property and Protection said that the destruction at Juukan Gorge was among the worst in recent history, likening it to the destruction of the Bamiyan Buddas in Afghanistan and the ancient Syrian city of Palmyra.

Rio Tinto claims it was not aware of the importance of the site, nor of the traditional owner’s wish for it to be preserved. But the PKKP Aboriginal Corporation rejected Rio’s suggestion that its representatives had failed to make clear their concerns for the site, and their wish for it to be preserved. “The high significance of the site was further relayed to Rio Tinto by PKKP Council as recently as March,” Burchell Hayes said.

Following the blast, Rio Tinto issued an apology to the PKKP people. “We are sorry for the distress we have caused,” Rio Tinto Iron Ore chief executive Chris Salisbury said in a public statement.

Several days after the public apology a leaked recording from a private Rio Tinto staff meeting found its way to The Australian Financial Review which reported that Salisbury told staff ” … we haven’t apologised for the event itself, per se, but apologised for the distress the event caused.” In a subsequent interview, Salisbury did not contradict the report, and repeatedly refused to directly answer when asked if the company was wrong to blow up the site, only repeating that they were sorry for the distress.

So, what is going on here — what can we make of Salisbury’s remark that the company had apologized not for the event itself but the distress it caused?

In taking the line that it did not know about the site’s significance, and attempting to insulate its apology from an admission of responsibility, Rio Tinto is trying to avoid moral blame. But does the separation hold? Can an agent be sorry for causing distress without ipso facto being responsible for causing it? And if so, does Rio’s attempt to excuse its actions from moral blameworthiness succeed?

The attribution of moral blame is not straightforwardly connected to the objective wrongness of an action carried out or caused by an agent. One way to assess the connection in any given case is to consider what conditions would have to be present for an agent to be held morally responsible, that is, to be blameworthy for an action.

It is possible to identify cases in which an agent is blameworthy even if an action is not in itself wrong; or, conversely, in which an agent is not blameworthy even if an action is wrong.

To give a relatively simple example, Jane intends to poison Joe by putting a white substance, which she believes to be arsenic, in his tea. It turns out Jane was mistaken, and the powder was only sugar; nothing happens to Joe so there is no objective moral wrong committed, however Jane’s intention to poison him is blameworthy. Conversely, if Jane accidentally poisons Joe by putting what she believes to be sugar, but what in fact turns out to be arsenic, in his tea, she is not (necessarily) blameworthy though the act of poisoning Joe is itself an objective moral wrong.

Here we can see that the salient elements for establishing blame are intention and knowledge. In the first case, Jane’s intention is morally blameworthy, even if the outcome is neutral. In the second case, though Jane has no intention to harm Joe, further questions arise about how Jane came to make this mistake, and whether she should reasonably have been expected to know that the substance she put in Joe’s tea was in fact arsenic rather than sugar.

In the case of Rio’s destruction of the Juukan Gorge cave we cannot know if it was Rio’s intention to blast the site over the strong objection of the PKKP owners, though some suspect that it was.

For an action to be morally wrong yet the agent not blameworthy, the agent must have an excuse for carrying it out which absolves them of responsibility. As Holly Smith suggests, “Ignorance of the nature of one’s act is the preeminent example of an excuse that forestalls blame.”

The question, then, is epistemic — for an agent to be held responsible, certain epistemic conditions need to be fulfilled. The first condition is that there is an awareness of the action (that the agent knows what she is doing); second the agent has to have been cognizant of the moral significance of the action; third the agent has to have been aware of the consequences of the action.

The first condition is obviously fulfilled, as the action of blasting the site was deliberate. The second condition of cognizance of the moral significance, together with the third condition of cognizance of consequences is, by Rio, under dispute.

In another statement, made subsequent to the leaked tape of his remarks, Salisbury said he had “taken accountability that there clearly was a misunderstanding about the future of the Juukan Gorge.”

It isn’t clear what having ‘taken accountability’ means, but the claim that it was a misunderstanding is an attempt to avoid blameworthiness by claiming that an epistemic condition is not fulfilled.

However, ignorance can itself be morally culpable. If (in the above example) Jane did not read the box when she could have, say, or if she ignored reasonable suspicions that someone had replaced the sugar with arsenic, then her ignorance does not excuse her of blame for poisoning Joe. It must be noted that there is disagreement among philosophers on this point; while some argue that an agent can be blamed for their ignorance, others maintain that, however criticizable it is, ignorance nonetheless exculpates the agent from moral blameworthiness.

On the former view, if Rio is culpable for its ignorance, that ignorance fails to shield the company from moral blame. This, to me, seems correct — and I would argue that even if we take Rio Tinto at its word that it was not aware of the significance of the site and the PKKP people’s wish for it to be preserved, the company has failed in its responsibility to the traditional owners and is indeed blameworthy.

I might add that taking Rio at its word here seems to me exceedingly generous, and I remind the reader that the PKKP people strenuously denied the suggestion that they had not made their wishes known to the company.

So, regarding the dubious distinction between apologizing for the distress caused but not for the action which caused it, Rio Tinto may say it is sorry, but without an accompanying willingness to accept responsibility, its apology is hollow. It appears the company has apologized from an ostensible obligation to do so, but shows little genuine remorse for this act of cultural destruction.