This article has a set of discussion questions tailored for classroom use. Click here to download them. To see a full list of articles with discussion questions and other resources, visit our “Educational Resources” page.

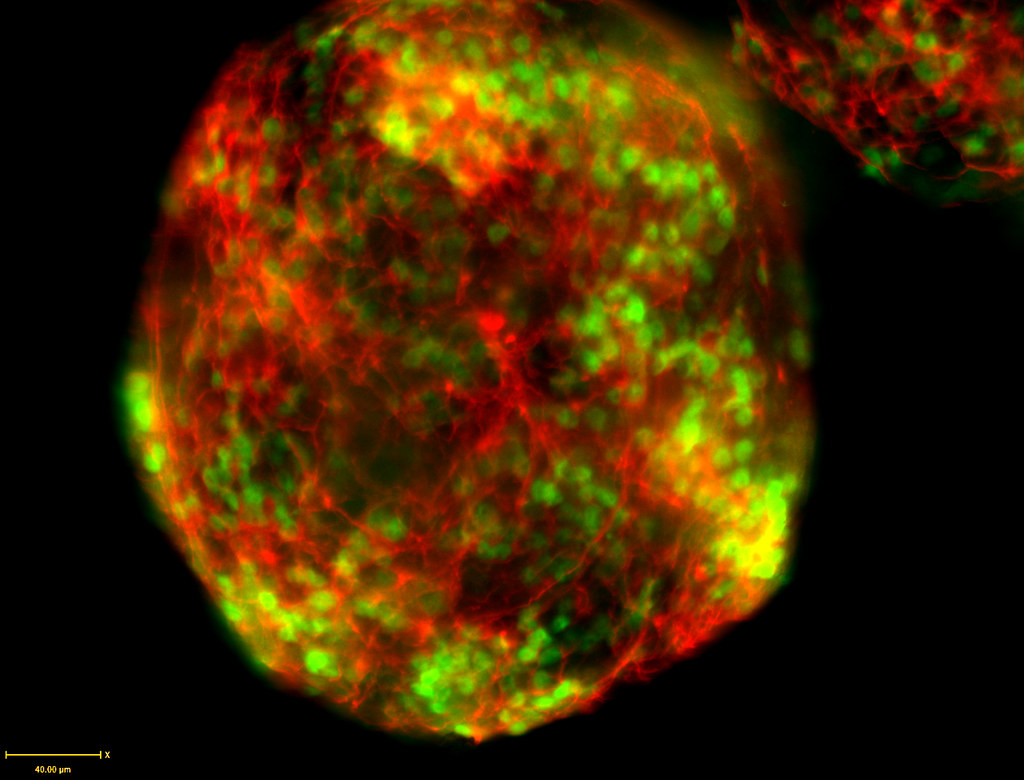

A 43-year-old with a deadly skin cancer is asking doctors to use the recent developments in CRISPR to experiment with treatments that may help him as well as advance medical understanding. Malakkar Vohryzek is offering to be a test subject, contacting a number of researchers and doctors asking if they would be interested in modifying his genetic code. Such treatment falls well outside approved parameters for human exposure to risk with the gene-editing technology, but the potential patient seems to be providing straightforward consent. In medicine and law, however, consent is often not enough. Currently the international scientific community remains critical of researchers in China that edited the genes of twin children last year, saying that such interference was premature and that the understanding of CRISPR and the impact on human subjects was not advanced enough for such research (for discussion see A.G. Holdier’s “Lulu and Nana: The Surprise of Genetically-Modified Humans”). Vohrysek’s case is interesting, though, because with a terminal illness and clearly expressed desire, why stick to standards that aim to promote and protect a subject’s welfare? If Vohrysek is willing to risk his health (what is left of it given his illness), why should doctors and researchers hesitate to proceed?

The ethics surrounding agreements or contracts incorporate a number of dimensions of our agency and the way we relate to one another. These standards attempt to take seriously the import of being able to direct one’s own life and the significance of the harm of manipulating the lives of others.

Paternalism is the term used to describe efforts to promote others’ best interests when those actions run counter to their expressed wishes. In such cases, someone believes that if a person’s will were effective, it wouldn’t promote what is in their best interests, and therefore interference is justified. The standard case of paternalism is that of a parent who overrules the will of a child. Say, for example, a 5-year-old wants ice cream for dinner but a parent disregards this preference and instead makes the child eat a nutritious meal believing that this will be better for the child. Typically, we think parents are morally justified in disregarding the child’s expressed preferences in circumstances like these. But when, and under what circumstances, paternalism can be justified outside of these clear-cut parent-child cases is much less clear. In Vorysek’s case, there is something paternalistic about not prioritizing the autonomous choice he is communicating. In general, regulatory standards are meant to promote subjects’ welfare and interests, but Vorysek isn’t a child, so what countervailing reasons apply here?

One class of cases where paternalistic interference is typically considered justified is where there isn’t a clear of expression of an agent’s will to interfere with in the first place. We may interpret the parent-child case in this way: a child hasn’t developed their full autonomous capabilities, therefore superseding their expressions of will when it runs counter to their best interests doesn’t seem as problematic as thwarting the will of a fully autonomous, mature adult. Vorysek, and other patients facing terminal prognoses who knowingly choose to expose themselves to risk, seem to be in a different class than those whose illness or condition of life diminishes their autonomy.

One barrier to truly just agreements is an unethical power dynamic founded on asymmetric information. For instance, if one party uses legal understanding and jargon to obscure the stakes and conditions of an agreement so that the other party can’t fully weigh the possible outcomes that they are agreeing to, this is intuitively not a fair case of agreement. These concerns are relevant in many legal contracts, for instance in end-user license agreements that consumers accept in order to use apps and software.

Another arena where there is often an asymmetry of technical understanding is in physician-patient exchanges (for discussion see Tucker Sechrest’s “The Inherent Conflict in Informed Consent”). In order to get informed consent from patients, physicians must communicate effectively about diagnoses, potential treatment options, as well as their outcomes and likely effects to patients who frequently do not have the breadth of understanding that the physician possesses. If a doctor does not ensure that the patient comprehends the stakes of the treatment choices, the patient may enter into agreements that do not reflect their priorities, preferences, and values. This asymmetric understanding is also the ethically problematic dimension of predatory lending, “the practice of a lender deceptively convincing borrowers to agree to unfair and abusive loan terms, or systematically violating those terms in ways that make it difficult for the borrower to defend against.”

But there remain further ethical considerations even when mutual understanding can be assured. It’s true that only when both parties to an agreement have a full grasp of the stakes and possible outcomes of the agreement is there the potential for each to weigh this information against their preferences, priorities, and values in order to determine whether the agreement is right for them. However, this doesn’t exhaust all ethical dimensions of making agreements. We could imagine that the 43-year-old patient seeking un-approved CRISPR treatments to be in such a position — he might understand the risks and not be mistaken about how the facts of the matter relate to his particular values, preferences, and priorities. What ethical reservations are left?

Exploitation refers to a type of advantage-taking that is ethically problematic. Consider a case where an individual with little money is offered $500 in exchange for taking part in medical research. It could be the case that this is the “right” choice for them — the $500 is sorely needed, say to maintain access to shelter and food, and the risk involved in the medical research is processed and understood clearly and the person determines that shelter and food outweigh the risk. In such cases, the ethical issue isn’t that a person may be entering agreements without understanding or against their best interests. Indeed, this individual is making the best choice in their circumstances. However, the structure of the choice itself may be problematic. The financial incentive for taking on unknown risk of bodily harm is a thorny ethical question in bioethics because of the potential exploitative relationship it sets up. When financial incentives are in place, the disadvantaged portion of a population will bear the brunt of the risk of medical research.

In order to avoid exploitation, there are regulatory standards for the kinds of exchanges that are permissible for exposing one’s body to risk of unknown harm, as in medical research. There are high standards for such research in terms of likelihood of scientific validity – the hypothesized outcome can’t just be an informed “guess,” for instance. Vorysek likely won’t find a researcher to agree to run experiments on him for fear that terminal patients, in general, will become vulnerable to experimentation. As a practice, this may be ethically problematic because patients are a vulnerable population and this vulnerability may be exploited — the ethical constraint on agreements can be a concern even when making the agreement may be both in the individual’s best interest and satisfying their will.

This, of course, leads to tensions and controversy. Should Vorysek and others in similar positions be able to use their tenuous prognosis for scientific gain? “If I die of melanoma, it won’t help anyone,” he said. “If I die because of an experimental treatment, it will at least help science.”