This post originally appeared June 9, 2015.

In my youth my parents would defend capitalism by saying that it incentivized work in contrast to communism. If you thought you could get paid the same amount whether you worked hard or not, you would see no reason to work hard or better. It isn’t just my parents. A recent This American Life podcast, “Same Bed, Different Dreams (transcript),” includes a recording smuggled out of North Korea in the early 1980s of Kim Jong-Il saying that North Korean filmmakers have no incentive to make creative and interesting work because of communism. How did everyone from one of the last communist dictators to my parents come to believe that capitalism incentivizes hard work, creative and inventive work, while communism does not?

It turns out that the men who defend and articulate the systems under dispute here–Adam Smith and Karl Marx–agree on quite a bit when it comes to what incentivizes workers. Workers work in order to eat. Smith and Marx agree that capitalists try to pay workers as close to whatever it costs to reproduce labor: “A man must always live by his work, and his wages must at least be sufficient to maintain him” (Smith, The Wealth of Nations, 61). To reproduce labor can be understood in two ways: to get it to come back again the next day or to add more labor to the force. In the first sense, to reproduce labor is to renew the body of the worker for more work. In the second sense, to reproduce labor is to produce more bodies of workers through biological reproduction. Both senses are biological reproduction, one is the furthering of energy in the same body and the other is procreative.

Smith explains the reproduction of labor in connection to the law of wages:

If this demand [for labor] is continually increasing, the reward of labour must necessarily encourage in such a manner the marriage and multiplication of labourers, as may enable them to supply that continually increasing demand by a continually increasing population. If the reward should at any time be less than what was requisite for this purpose, the deficiency of hands would soon raise it; and if it should at any time be more, their excessive multiplication would soon lower it to this necessary rate. The market would be so much understocked with labour in the one case, and so much overstocked in the other, as would soon force back its price to that proper rate which the circumstances of the society required. It is in this manner that the demand for men, like that for any other commodity, necessarily regulates the production of men, quickens it when it goes on too slowly, and stops it when it advances too fast (71).

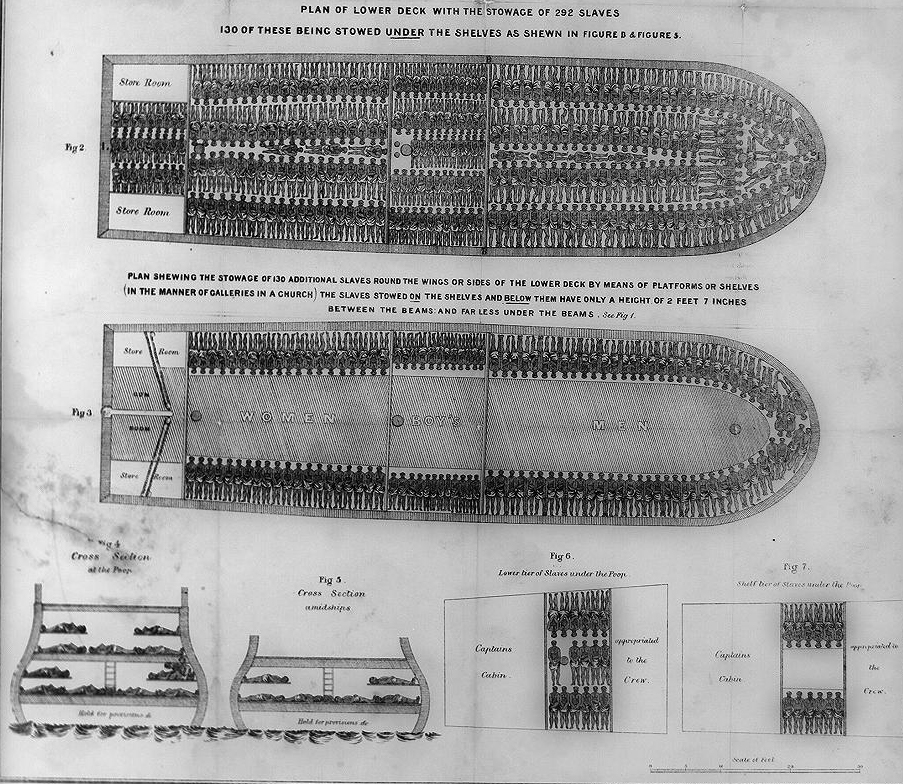

You need workers, so you have to attract them through wages. You pay them. They produce. You pay them. But this doesn’t seem to produce wealth. To produce wealth you do two things: you invest your capital into machines and you divide the tasks of labor. So then you need more workers. You produce more. The more you divide labor, the less your workers needs skills, so the less you need to pay them. But demand cannot keep up with this cycle. Demand levels off and now you don’t need those workers. What happened while you were needing more workers is that the workers were responding to the labor market demand for more workers by having more workers, ie. children. Now they have more workers to satisfy the market, but the market is glutted. Demand levels off. You can pay your workers a whole lot less because you don’t need to pay as much to reproduce the worker because if that worker can’t sustain herself to come back the next day, someone else who wasn’t working can step in to fill that worker’s place.

In a capitalist society, the incentive to work is to live. The capitalist has an interest in keeping the worker as close to the edge of living so that she will work for a lower wage. Even Smith warns against this outcome of his own system when he says that “Where wages are high, accordingly, we shall always find the workmen more active, diligent, and expeditious, than where they are low” (72).

The capitalist’s incentive is productivity and the capitalist might realize that she can pay workers more and find more productivity. But she can also realize that she can pay them less than they are worth (less than the value they produce by adding labor to the raw materials on which they work), and still recoup a profit. The reason the capitalist can pay the worker less than she is worth is that she must work in order to eat. There is very little bargaining when one would have to walk away to protest and to walk away is to die. Part of the problem with supposing that capitalism incentivizes workers to work harder is that it assumes that workers recoup the benefits of their increased productivity. But if you work a wage job in capitalism, you actually find yourself in a more precarious situation and get paid a smaller percentage of the value that you produce the more productive you are. The capitalist pays you an hourly wage. Say you work eight hours and are paid ten dollars an hour for 80 bucks a day. If you make a widget that will be sold for $12 and it costs the capitalist $2 in materials, you add $10 in value for the widget. Let’s say you produce 8 in a day. Then the capitalist is paying you for as much as you have produced. You are paid as much as the value you produce. The capitalist examines this situation and wonders whether you can live on less in order to reduce the wage and make more profit or she can find ways to make you more productive by dividing labor or giving you some tools. So the next day you make 16 in a day. You are really productive. But you went from getting 100% of the value you added to 50% of the value you added. Now really, what’s your incentive to work harder? The harder you work now, the more it costs to reproduce your labor, but you aren’t producing more for yourself but for the owner. Perhaps you think this makes you more indispensable so you are more secure in your work? But no, as the labor is divided in smaller parts to make workers more productive and tools are added to make you more productive as well, the easier it is to replace you and so the more willing you are to work for less.

So when people say that capitalism provides an incentive where communism does not, they are saying that capitalism does a better job of keeping people in the precarious position where they must work for whatever little they can get in order to live. The harder workers work the less of their own value they recoup. So what does capitalism incentivize? The problem with saying it incentivizes people to work harder and be more creative is that it assumes that everyone has the same incentives in capitalism–the owners and the workers. But this is not the case. Smith argues that everyone pursues her self-interest in capitalism, but the interest of the capitalist is to be more creative about how to make more money by creative uses of machinery and labor, reading the market well, and paying labor less while the interest of the worker is to be paid more so that she can stop worrying about the day-to-day concern for living. The better the capitalist organizes work, the more she recoups. The harder the worker works, the less she recoups.

Dan Horn, columnist at the The Cincinnati Enquirer interviewed a middle-class citizen, Donna Palmatary, about the lifestyle and income of the middle class for a USA Today article on the 2015 Pew Charitable Trust Study on the shrinking middle class, who aptly distinguishes the middle class from both owners and workers when she says, “You have to work for what you have.” Owners don’t work for what they have, and the workers don’t have what they work for.