Removing Slavery from Textbooks

Earlier this academic year, Roni Dean-Burren, a Houston mother, posted on Facebook in response to a passage in her ninth-grade son’s history book, which referred to slaves—not as slaves—but as “workers” and “immigrants.” The post went viral, influencing the publisher “to apologize, correct the caption and offer — free of charge — either stickers to cover it up or corrected copies of the book to schools that want to replace their old ones.” They did not issue a recall of the misleading, erroneous books.

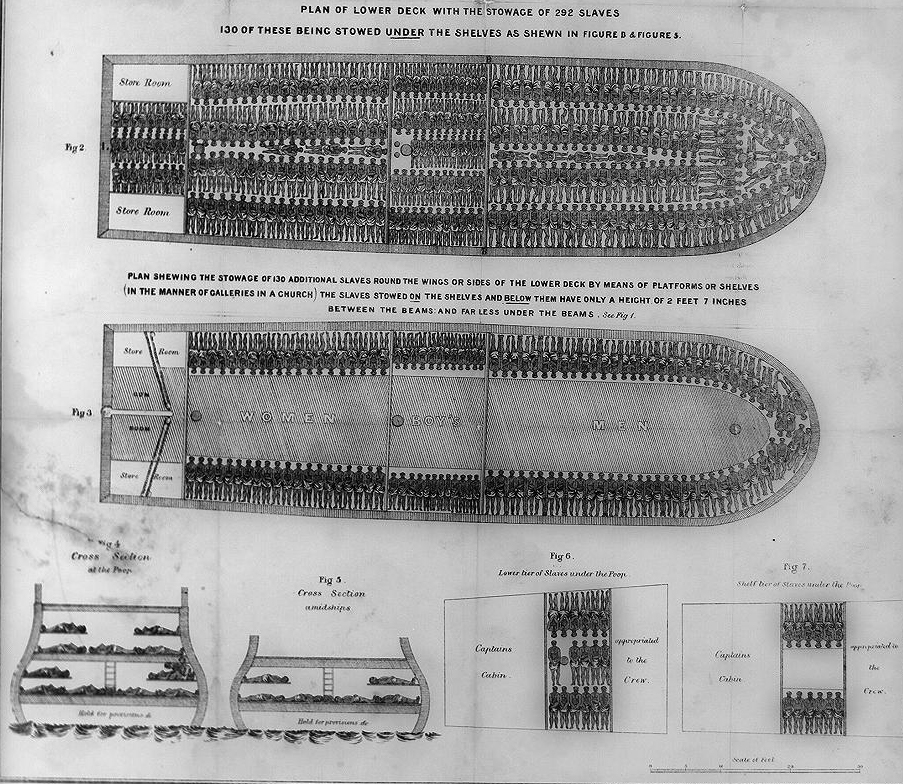

In McGraw-Hill’s “World Geography” textbook, a caption, overlapping a map of the United States, points generally to South Carolina and reads: “The Atlantic Slave Trade between the 1500s and 1800s brought millions of workers from Africa to the southern United States to work on agricultural plantations.” The page is titled: “Patterns of Immigration.” There is no mention of the violent removal of Africans from their homes and families. The caption uses the verb “brought,” a euphemism that atrociously misrepresents the inhumane and deadly transportation of Africans across the Atlantic. The caption does not even present the existence of slave owners or traders; rather The Oxford English Dictionary defines “bring” as “take or go with (someone or something) to a place: she brought Luke home from hospital.” As even the OED’s hospital example displays, bring generally has a positive connotation. It converts slavery’s malicious pillage, cruel exploitation, and inhumane treatment of Africans into an opportunity for employment on plantations. This gross misrepresentation is followed by a passage on the next page, which validates the struggle of white indentured servants: “‘an influx of English and other European peoples, many of whom came as indentured servants to work for little or no pay,’ but made no mention of how Africans came to the country.”

McGraw-Hill’s inaccurate depiction of slavery is not the first controversy involving Texas’ textbooks: “In 2010, the Texas Board of Education approved a social-studies curriculum that put a conservative stamp on history and economics textbooks, including emphasizing Republican political achievements and movements.” These changes included listing “sectionalism” and “states’ rights” as the causes of the Civil War, followed lastly by “slavery.” The nationalistic ideal that these laws encourage end up “stressing the superiority of American capitalism, questioning the Founding Fathers’ commitment to a purely secular government and presenting Republican political philosophies in a more positive light.”

Even fellow conservatives challenged “the Texas board for minimizing difficult parts of the nation’s past.” According to “The Texas Tribute,” Rod Paige, the Republican education secretary during President W. Bush’s term, “asked the board to systematically review its treatment of slavery and civil rights”: “‘I’m of the view that the history of slavery and civil rights are dominant elements of our history and have shaped who we are today,’ he said. ‘We may not like our history, but it’s history, and it’s important to us today.’” Paige’s request was met with disrespect, protest, and resistance.

Based on the state’s educational history and legislative context, can we trust McGraw-Hill’s CEO David Levin and his claim that this was simply “a mistake,” and that “the book was reviewed by many people inside and outside the company” all of whom did not notice such an error? Since “Texas is the second-largest consumer of textbooks in the country, after California,” it has a great influence on the textbook publishing industry. Could McGraw-Hill have been gaining favor and appeasing the wishes of Texas’ legislation as a tactical, professional move? Have textbooks become a form nationalistic propaganda, products of politicians’ ideals?

Slavery was one of our nation’s greatest atrocities. Its trauma reaches across generations, shaping our current America. We cannot change the past, but we have the obligation to acknowledge it, and a simple “slaves” sticker—hiding the permanent, printed “workers” beneath—is not going to cut it.