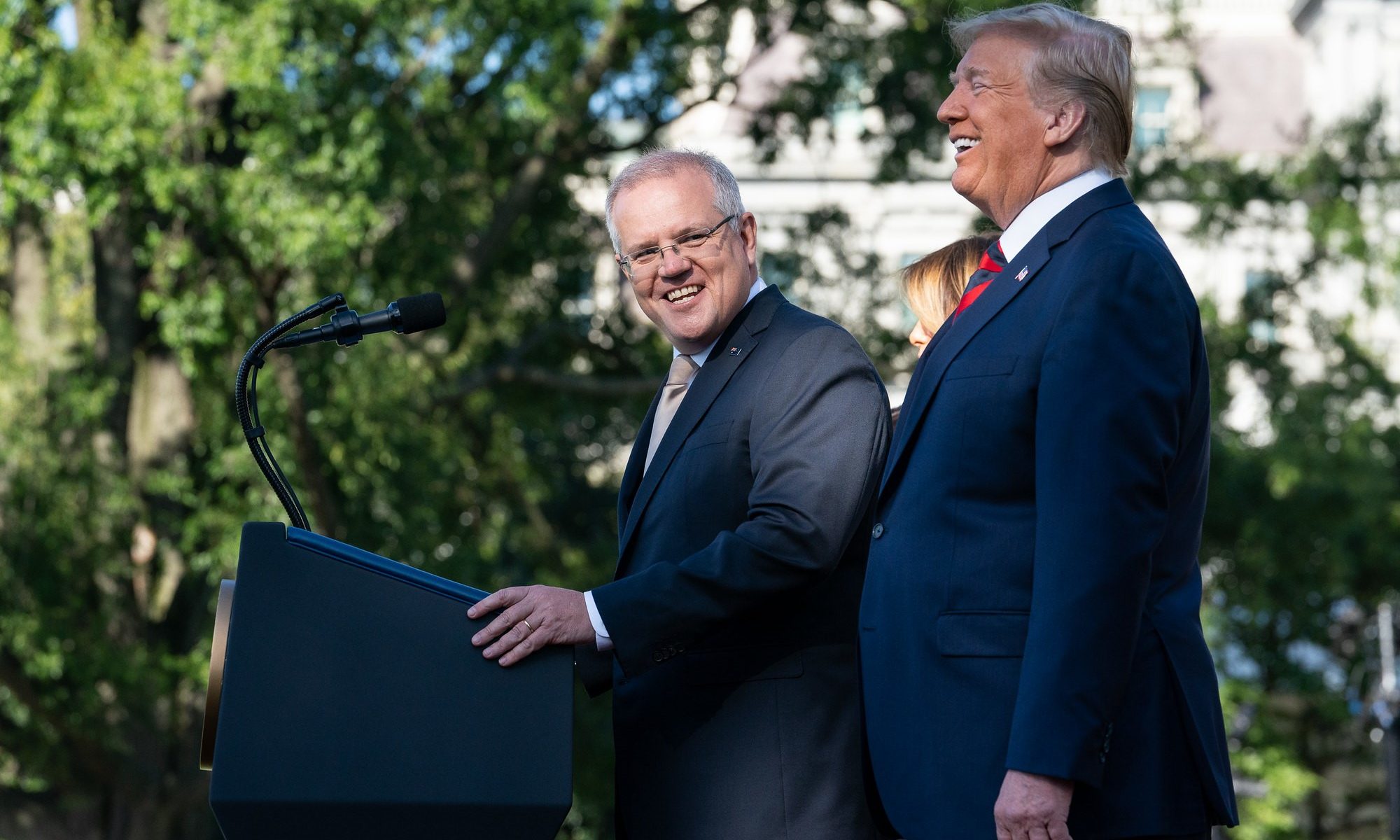

In the same week that Donald Trump was being pilloried for taking classified documents from the White House, Australia was facing its own crisis of executive overreach. Reports surfaced that our former Prime Minister, Scott Morrison, had ignored the unwritten rules of Australian democracy and given himself responsibility for a variety of government portfolios, extending his power way beyond his remit. This extraordinary concentration of power in the hands of one man represented a significant threat to our venerable system of government. It also raises an interesting question about the nature of democracy: what is the best way to ensure that the voices of the population are represented in the halls of power?

What’s so great about democracy?

There are a couple of normative benefits to democracies over alternative forms of government. One is that executive power is limited, saving us from the sort of governmental overreach which characterizes totalitarian regimes. As political philosopher George Kateb wrote, “in contrast to dictatorship, oligarchy, actual monarchy or chieftainship, or other forms [of government], representative democracy signifies a radical chastening of political authority.” Both presidential and parliamentary democratic systems achieve this chastening by dividing powers between branches of government and providing checks and balances on executive authority. (That said, American presidents tend to have far more individual power than Australian prime ministers – despite the separation of powers in the U.S., executive orders are incredibly common).

For this chastening to be successful, however, strong constitutional or legal protections must be in place to ensure that power doesn’t become overly concentrated.

As we’ll return to in a moment, Australia’s reliance on unwritten laws, precedent, and tradition means that we are at risk of unscrupulous actors accumulating excessive power and wielding unfettered political authority.

Another positive of representative democracy is right there in the name – it is representative. Parliament, or congress, is made up of people from across the nation, and is supposed to represent the interests of those people; allowing them a say in, and control over, the laws and institutions that determine their lives. Australian philosopher Elaine Thompson equated representation with fairness: democratic systems are representative only insofar as “the parliament is accepted [by the people] as representing the people who elected it.”

The Australian parliamentary system

Before diving into issues of representation, it’s worth giving some background on Australian governance. There are quite a few differences between the Australian and American political systems but the major one is that, in Australia, we don’t directly elect our leader. Both Australians and Americans vote for local representatives and for senators to represent their states.

But whereas every American has the opportunity to vote for their president (ignoring the vagaries of the electoral college), Australia’s prime minister is chosen by the aforementioned local representatives.

Currently, the Labor party holds a majority in the House of Representatives and have elected one of their own, Anthony Albanese, to the Office of Prime Minister. But if one party doesn’t hold a majority in their own right, parties must work together to form governing coalitions. Once a prime minister is elected, they select a ministry of members of parliament who are given responsibility for different portfolios – things like health, education, trade, foreign affairs, and so on. The minister is then supposed to wield authority over their area, meaning they make the big decisions on policy matters and (occasionally) take responsibility when things go wrong.

So, the Australian flavor of representative democracy is quite different to the American one. But if representation is the goal, what offers better representation – parliamentary or presidential systems?

President or Parliament?

On the one hand, American presidents are directly elected by the whole nation, which might make them more representative than Australian prime ministers. Presidential candidates can’t afford to only appeal to small minorities or particular geographical areas: they have to garner support across the country. Theoretically, at least, this should temper their wilder inclinations as they attempt to cast as broad a net as possible (although empirical evidence might suggest otherwise). On the other hand, it might be unreasonable to think that anybody could truly reflect the diversity of a huge country like the U.S.

Unlike presidential candidates, local representatives can (and perhaps should) pander only to their narrow constituencies. This means they can take up local matters or focus on representing minority groups, although that narrow focus can mean they are less representative of the nation as a whole.

In Australia’s system, the issue of representative leadership is somewhat offset by the existence of parliament: although any one member might not be particularly representative of the entire nation, the parliament as a whole – all 151 members of the house, plus the senate – ought to offer a decent reflection of the nation. And because decision-making isn’t centralized in the prime minister, it’s not such a huge issue that they are only elected to parliament by a small proportion of the population. By spreading decision-making responsibility across members of parliament, representing different people from different places, we avoid the need to have any single, broadly representative, head of state or government.[i] Lately, however, this hasn’t been happening.

The secret ministries

Last week, news surfaced that during the pandemic (now former) Prime Minister Scott Morrison secretly swore himself in to five different ministries: Home Affairs; Finance; Health; Industry, Science, Energy and Resources; and Treasury. So rather than having responsibility for policy decisions spread across members of parliament, we had an unprecedented concentration of power in Australia – something closer to the American presidential system than the system we are used to.

What’s worse, we didn’t get any of the benefits of the presidential system.

Instead of having a president elected by the entire country and entrusted with heading government, we had a prime minister with a huge amount of centralized power elected by a small group of people from south-east Sydney – an area richer, whiter, and more religious than Australia as a whole.

Essentially, we had the worst of both systems: an unrepresentative leader with too much individual power. Thompson’s fairness was nowhere to be seen, and the chastening of power that Kateb wrote about had been eroded from within.

Despite public outrage and condemnation of Morrison’s actions (including from those in his own party), they were perfectly legal – even if they “fundamentally undermined” the practice of responsible government. Luckily, Morrison did little with his extreme power, other than cancel a permit for a gas project off the coast of Sydney. Next time, however, we might not be so fortunate. What the Morrison saga shows us is that regardless of whether we live in a presidential or parliamentary system, we can’t rely on convention, tradition, and unwritten rules. Strong laws limiting individual power are essential to the creation of democracies which truly represent the will of the people.

[i] (For an excellent overview of the strengths and weaknesses of parliamentary and presidential systems, check out political scientist Steffen Ganghof’s recent book).