“Are We Facing Nuclear War?” — The New York Times, 3/11/22

“Pope evokes spectre of nuclear war wiping out humanity” — Reuters, 3/17/22

“The fear of nuclear annihilation raises its head once more” — The Independent, 3/18/22

“The threat of nuclear war hangs over the Russia-Ukraine crisis” — NPR, 3/18/22

“Vladimir Putin ‘asks Kremlin staff to perform doomsday nuclear attack drill’” — The Mirror, 3/19/22

“Demand for iodine tablets surge amid fears of nuclear war” — The Telegraph, 3/20/22

“Thinking through the unthinkable” — Vox, 3/20/22

The prospect of nuclear war is suddenly back, leading many of us to ask some profound and troubling questions. Just how terrible would a nuclear war be? How much should I fear the risk? To what extent, if any, should I take preparatory action, such as stockpiling food or moving away from urban areas?

These questions are all, fundamentally, questions of scale and proportion. We want our judgments and actions to fit with the reality of the situation — we don’t want to needlessly over-react, but we also don’t want to under-react and suffer an avoidable catastrophe. The problem is that getting our responses in proportion can prove very difficult. And this difficulty has profound moral implications.

Everyone seems to agree that a nuclear war would be a significant moral catastrophe, resulting in the loss of many innocent lives. But just how bad of a catastrophe would it be? “In risk terms, the distinction between a ‘small’ and a ‘large’ nuclear war is important,” explains Seth Baum, a researcher at a U.S.-based think tank, the Global Catastrophic Risk Institute. “Civilization as a whole can readily withstand a war with a single nuclear weapon or a small number of nuclear weapons, just as it did in WW2. At a larger number, civilization’s ability to withstand the effects would be tested. If global civilization fails, then […] the long-term viability of humanity is at stake.”

Let’s think about this large range of possible outcomes in more detail. Writing during the heights of the Cold War, the philosopher Derek Parfit compared the value of:

-

- Peace.

- A nuclear war that kills 99% of the world’s existing population.

- A nuclear war that kills 100%.

Everyone seems to agree that 2 is worse than 1 and that 3 is worse than 2. “But,” asks Parfit, “which is the greater of these two differences? Most people believe that the greater difference is between 1 and 2. I believe that the difference between 2 and 3 is very much greater.”

Parfit was, it turns out, correct about what most people think. A recent study posing Parfit’s question (lowering the lethality of option 2 to 80% to remove confounders) found that most people thought there is a greater moral difference between 1 and 2 than between 2 and 3. Given the world population is roughly 8 billion, the difference between 1 and 2 is an overwhelming 6.4 billion more lives lost. The difference between 2 and 3 is “only” 1.6 billion more lives lost.

Parfit’s reason for thinking that the difference between 2 and 3 was a greater moral difference was because 3 would result in the total extinction of humanity, while 2 would not. Even after a devastating nuclear war such as that in 2, it is likely that humanity would eventually recover, and we would lead valuable lives once again, potentially for millions or billions of years. All that future potential would be lost with the last 20% (or in Parfit’s original case, the last 1%) of humanity.

If you agree with Parfit’s argument (the study found that most people do, after being reminded of the long-term consequences of total extinction), you probably want an explanation of why most people disagree. Perhaps most people are being irrational or insufficiently imaginative. Perhaps our moral judgments and behavior are systematically faulty. Perhaps humans are victims of a shared psychological bias of some kind. Psychologists have repeatedly found that people aren’t very good at scaling up and down their judgments and responses to fit the size of a problem. They name this cognitive bias “scope neglect.”

The evidence for scope neglect is strong. Another psychological study asked respondents how much they would be willing to donate to prevent migrating birds from drowning in oil ponds — ponds that could, with enough money, be covered by safety nets. Respondents were either told that 2,000, or 20,000, or 200,000 birds are affected each year. The results? Respondents were willing to spend $80, $78, and $88 respectively. The scale of the response had no clear connection with the scale of the issue.

Scope neglect can explain many of the most common faults in our moral reasoning. Consider the quote, often attributed to Josef Stalin, “If only one man dies of hunger, that is a tragedy. If millions die, that’s only statistics.” Psychologist Paul Slovic called this tendency to fail to conceptualize the scope of harms suffered by large numbers of people mass numbing. Mass numbing is a form of scope neglect that helps explain ordinary people standing by passively in the face of mass atrocities, such as the Holocaust. The scale of suffering, distributed so widely, is very difficult for us to understand. And this lack of understanding makes it difficult to respond appropriately.

But there is some good news. Knowing that we suffer from scope neglect allows us to “hack” ourselves into making appropriate moral responses. We can exploit our tendency for scope neglect to our moral advantage.

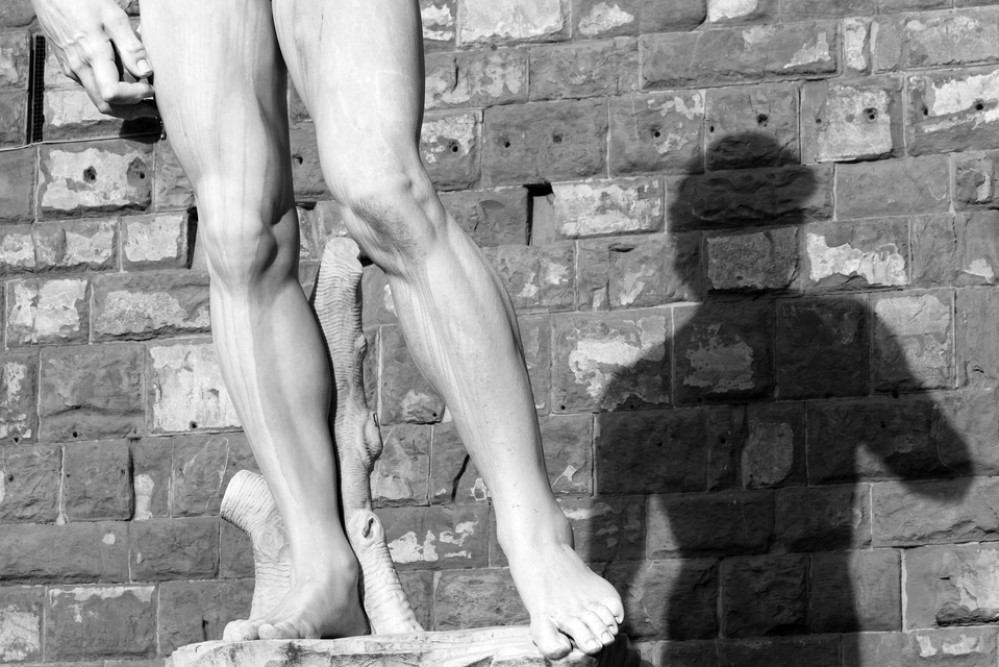

If you have seen Steven Spielberg’s Schindler’s List, then you will remember a particular figure: The girl in the red coat. The rest of the film is in black and white, and the suffering borders continually on the overwhelming. The only color in the film is the red coat of a young Jewish girl. It is in seeing this particular girl, visually plucked out from the crowd by her red coat, that Schindler confronts the horror of the unfolding Holocaust. And it is this girl who Schindler later spots in a pile of dead bodies.

The girl in the red coat is, of course, just one of the thousands of innocents who die in the film, and one of the millions who died in the historical events the film portrays. The scale and diffusion of the horror put the audience members at risk of mass numbing, losing the capacity to have genuine and appropriately strong moral responses. But using that dab of color is enough for Spielberg to make her an identifiable victim. It is much easier to understand the moral calamity that she is a victim of, and then to scale that response up. The girl in the red coat acts as a moral window, allowing us to glimpse the larger tragedy of which she is a part. Spielberg uses our cognitive bias for scope neglect to help us reach a deeper moral insight, a fuller appreciation of the vast scale of suffering.

Charities also exploit our tendency for scope neglect. The donation-raising advertisements they show on TV tend to focus on one or two individuals. In a sense, this extreme focus makes no sense. If we were perfectly rational and wanted to do the most moral good we could, we would presumably be more interested in how many people our donation could help. But charities know that our moral intuitions do not respond to charts and figures. “The reported numbers of deaths represent dry statistics, ‘human beings with the tears dried off,’ that fail to spark emotion or feeling and thus fail to motivate action,” writes Slovic.

When we endeavor to think about morally profound topics, from the possibility of nuclear war to the Holocaust, we often assume that eliminating psychological bias is the key to good moral judgment. It is certainly true that our biases, such as scope neglect, typically lead us to poor moral conclusions. But our biases can also be a source for good. By becoming more aware of them and how they work, we can use our psychological biases to gain greater moral insight and to motivate better moral actions.