In Three Identical Strangers, we learn of a set of triplets that was separated when they were 6 months old and discovered each other at 19. Robert Shafran, Edward Galland, and David Kellman were excited to find each other and made instant connections. However, they found their separation was part of a confidential experiment. Continue reading “Nature, Nurture, and Unknown Harms”

“Unbearable Suffering” and Mental Illness

Trigger warning: suicide attempts, multiple mental illness mentions

This article has a set of discussion questions tailored for classroom use. Click here to download them. To see a full list of articles with discussion questions and other resources, visit our “Educational Resources” page.

List of international suicide hotlines: http://ibpf.org/resource/list-international-suicide-hotlines

Aurelia Brouwers’ Instagram bio is terse and pointed: “BPD, depression, PTSD, anxiety etc. Creative. Writer. Gets euthanasia Januari [sic] 26. Fights till then for this subject.”

Brouwers was a twenty-nine year old Dutch woman who suffered from multiple mental disorders. She received her first diagnoses of depression and Borderline Personality Disorder at the age of twelve. As she recounts: “Other diagnoses followed – attachment disorder, chronic depression, I’m chronically suicidal, I have anxiety, psychoses, and I hear voices.” After an estimated twenty failed suicide attempts, Brouwers thought she found the solution to her suffering via euthanasia or physician-assisted suicide (EAS). EAS has been legal in the Netherlands since 2002, but Brouwers faced obstruction as her request was refused by multiple doctors. She finally turned to The Hague’s End of Life clinic, which approved her request and set a date for January 26 of this year. Scenes from Brouwers’ last fortnight of life were recorded by RTL Nieuws journalist Sander Paulus, who noted the young woman’s ongoing mental distress as well as the conviction with which Brouwers anticipated her euthanasia date. Footage featured by the BBC shows Brouwers collectedly making plans for her cremation ceremony with a funeral consultant. On January 26, surrounded by loved ones and two doctors, Brouwers consumed a liquid poison and “went to sleep.”

Brouwers’ case stoked vigorous debate in the Netherlands and elsewhere regarding the intent of euthanasia legislation. Her youth is one point of contention. Another factor is the nature of her affliction. In the discourses following Brouwers’ life, we see evidence of an assumed distinction between physical and psychiatric disorders. Journalist Harriet Sherwood went so far as to note in the tagline for her Guardian article that ”there was nothing wrong with her [Brouwers] physically.”

While psychiatric disorders are still primarily diagnosed via mental and behavioral markers, it is not strictly correct to assume that mental health disorders lack physical foundations. Often, the ways in which we speak of mental disorders reveal our imperfect knowledge of the biological elements (as differentiated from the more traditionally observed psychosocial components) of mental disease. This relative ignorance exists in part because researching biomarkers for psychiatric disease is a complex undertaking. What is known is that mental illnesses can often be life-long conditions that require ongoing treatment, treatment that appears to have been provided in Aurelia Brouwers’ situation.

The 2002 Dutch act exempting physicians from prosecution in specific EAS cases requires ”due care” by the attending doctor. This includes ascertaining unbearable suffering on the part of the patient without hope of improvement. The Netherlands is joined in this relatively open model by other European nations, including Belgium, Luxembourg, and Switzerland. Several American states, the Australian state of Victoria, and Canada also allow EAS, but in much more restricted circumstances mirroring the “Oregon model,” which stipulates a terminal illness with established life expectancy.

Arguments in favor of euthanasia often rest on the basis of respect for individual autonomy and on compassionate grounds. Here, for the sake of simplicity, I assume ethical assent to these grounds in support of voluntary euthanasia or physician-assisted suicide which is at the informed, long-standing behest of the patient. This is the only form of active euthanasia currently legal anywhere (whereas what some call ”passive” euthanasia or the withdrawal of futile treatment is considered to be normal medical practice). These moral justifications – autonomy and compassion – are taken as reasonable in states in which EAS is legalized. In the Netherlands, however, where EAS has been legal for sixteen years, Brouwers was initially refused by several doctors, and garnered national attention. Why?

Brouwers’ example seems to challenge notions of what constitutes “unbearable suffering,” impossibility of improvement, and “terminal” conditions. Popular conceptions of mental illness present it as something that one can “overcome” through patience or willpower, although the same perceptions do not apply to a broken bone or a cancer diagnosis. Dutch psychiatrist Dr. Frank Koerselman, speaking to the BBC, notes that Borderline Personality Disorder, from which Brouwers suffered, is known to decline in severity after the age of 40. But BPD was only one of Brouwers’ multiple diagnoses, which taken together, caused her immense suffering. Along these lines, some argue that her mental disease was itself terminal, as does Kit Vanmechelen in the BBC article. Brouwers had already engaged in numerous, though incomplete, suicide attempts.

What happens, though, when we allow EAS for psychiatric suffering as well as physical suffering (the more traditionally accepted justification)? As a society, our understanding of mental suffering does not seem to be as advanced as that of physical suffering (only recently was it discovered that emotional pain activates neural correlates similar to physical pain).

Many believe that it is a mistake to open this door. Dr. Koerselman opposes EAS for psychiatric disorders, in part because he posits it is not possible to distinguish a rationalized decision to die from a symptom of mental disease itself. On the other hand, a recent study of Belgian mental health nurses’ attitudes toward euthanasia for unbearable mental suffering found a widely positive response. Nurses were the subjects for this study because of their closeness to patients’ lives and frequent role as intermediate and advocate between patients and doctors.

Ethics is about individual cases, as well as the general principles that they reveal or elicit along the way. The case of Aurelia Brouwers is undeniably a tragic one, although Brouwers herself appeared to find some peace in her capacity to make an informed choice, supported by medical care. But what her life surely reveals is that we need to invest more in exploring the genesis and maintenance of mental disorders within our societies. One in four people world-wide will suffer from some form of mental illness. We need to invest more in understanding the biological bases of mental illness, as well as the social structures that are implicated in psychiatric disorders’ psycho-social components. In the words of Brouwers, “I think it’s really important to do this documentary [of Brouwers’ life] to show people that mental suffering can be so awful that death, in the end, is the lesser of two evils.” As a society, we need to do better by those who experience mental pain.

Insecticidal Tendencies: Insects as Candidates for Ecological Ethics

Our world is vanishing in ways we do not always see or have pressing interest in, let alone regard as having moral or ethical consequence. Two recent studies in France have reported “catastrophic” declines in bird populations in the French countryside, with a total of one third of birds disappearing over the past 17 years and some species seeing declines of 50-90 percent. The culprit, according to researchers, is the large-scale use of pesticides in a once idyllic part of the world now dominated by industrial agriculture and monocultural farming practices (the growing of only one type of crop). We continue to be faced with the image of “silence” Rachel Carson provided us, in her seminal work on the ecological effects of chemical pesticides, in which “spring now comes unheralded by the return of the birds.” While the “indirect” harms that pesticides have on other creatures requires complex analysis, one effect of indiscriminate use is the large-scale destruction of avian food sources, forcing their starvation or migration elsewhere. Germany and France, another study in 2015 found as part of a larger European trend, have lost 80 percent of their flying-insect biomass over the past 30 years. The lesson is, or should be, that causality in nature does not stop where we want it to. Continue reading “Insecticidal Tendencies: Insects as Candidates for Ecological Ethics”

What’s Wrong with Hypocrisy?

Much has been written about the recent grand jury report revealing both an epidemic of extreme sexual abuse among Roman Catholic parishes in Pennsylvania and a conspiracy by church leaders to quietly cover up the crimes. The numbers are shocking: over 300 priests across 54 counties abused more than 1000 victims over the course of at least 80 years. Of course, sexual assault of any stripe is abhorrent, yet the moral hypocrisy evident in this case makes this story particularly cruel. Not only have the “predatory priests” damaged a thousand immediate victims, but the ripple effects of their decisions to twist their respected social positions into such corrupted outlets for their own selfish evils will inevitably taint the faith of a generation of Roman Catholics or more.

Indeed, it is bad enough to be a victim of injustice, but when the crime is performed by one who claims a position of moral authority, the injustice is multiplied. One can do wrong without being hypocritical, but one cannot be a hypocrite without doing wrong; in fact, hypocrisy typically compounds the painful consequences of evil.

In chapter two of her 1963 book On Revolution, German philosopher Hannah Arendt dubs hypocrisy “the vice of vices” on the grounds that it is inescapably indefensible. Any other vice, she argues, could feasibly be justified from the right perspective, but hypocrisy alone is bereft of any possible integrity: “Only crime and the criminal, it is true, confront us with the perplexity of radical evil; but only the hypocrite is really rotten to the core.”

On one level, being a good person – and being known for being a good person – affords an individual certain social benefits. Moral hypocrisy amounts to a person attempting to get those benefits without actually being the moral person they appear to be. In many cases, moral integrity requires some level of self-sacrifice; if a person can receive acclaim for being self-sacrificial without actually sacrificing anything, then that person selfishly comes out ahead. However, to do so means not only committing to being a moral hypocrite, but also to committing additional immoral acts such as lying or threatening those who know the truth to hide your secret. Once revealed, the moral hypocrite’s victims are not limited only to those affected by their explicit crimes: the dissonance suffered by those whom the hypocrite played for fools must also be considered.

And perhaps the most rotten hypocrites of all are those who pretend to be moral while hiding their sins and set out to publicly condemn others.

In his 1831 novel The Hunchback of Notre Dame, Victor Hugo introduced the world to the villainous Claude Frollo, the respected archdeacon of the famous French cathedral whose obsession with pious chastity gives way to an uncontrollable lust for the beautiful Esmeralda. By the end of the novel, Frollo’s bitterness has led him to betray his surrogate son, stab Esmeralda’s lover, and even turn Esmeralda herself over to be executed for a crime that Frollo committed simply because she continues to reject his advances. When Frollo himself is pushed over the edge of Notre Dame’s roof, the average reader feels little remorse for the death of the spiteful hypocrite.

In the case of most moral hypocrites, the problem is twofold: firstly, the hypocrite has committed an immoral act; secondly, he has simultaneously lied about and/or hidden that act, while also unjustly receiving moral praise from his peers. In Frollo’s case, the problem is threefold: he has committed a crime, he has hidden it, and he continues to publically crusade against others who are guilty of the same crimes.

Consider the perspective of one of Frollo’s fictional parishioners: they may agree with Frollo’s condemnation of sexual licentiousness, even once they discover that Frollo himself is guilty of that very act. On one hand, Frollo’s public words are correct; on the other, Frollo’s private actions are not – to try and make sense of such a disjunction can be remarkably unsettling. How can one easily reconcile the familiar picture of a respectable leader with the new knowledge that the person was dishonestly putting on a show for the public? Such lies cast a pall over Frollo’s entire public persona, calling into question even those things that most people would otherwise take for granted. This means that Frollo’s crimes are not limited only to his violent assaults on Esmeralda or Phoebus; the angst that his moral hypocrisy would force upon innocent observers is an additional wrong that complicates a situation already dripping with moral hazards.

On some level, studies suggest that most people are guilty of hypocrisy on some level. One experiment performed at the University of Kansas in the late 90s asked individuals to privately choose between doing two tasks: both tasks were left vague, but one was described as boring with no reward while the other would offer the person a chance to win a prize in a raffle. The subject was told that she could select which task she would be assigned and which task would go to her unseen counterpart; in 70-80% of cases, the individuals assigned themselves the raffle-eligible task and gave the boring one to the stranger.

Then, in a second round, the researchers explained the same parameters, but suggested that the subject flip a coin to randomly (and, therefore fairly) assign the raffle task and the boring task. The results here were surprising: the subjects who chose not to flip the coin saw the same rate of task assignments as in round one (roughly 80-90% of people chose the raffle-eligible task for themselves), but the subjects who did flip the coin also saw the same rate of task assignments as in round one (85-90%)! One would think that the subjects who used the coin would have task assignment rates closer to 50% unless there was some element of cheating going on behind the scenes.

However, many moral hypocrites willfully admit their limitations (in the Kansas study, for instance, cheating subjects routinely ranked themselves as having done something immoral at the end of the experiment). Perhaps this suggests that the ambiguity in many moral cases allows for some degree of natural forgiveness to be reasonably extended to fallible agents; to claim a form of moral infallibility, as Frollo does when speaking of morality from the position of a teaching authority, inversely changes an observer’s willingness to forgive a hypocrite.

The fallout from the Pennsylvania Sex Abuse Scandal has already led to responses from Catholics around the country as they have renamed schools, implemented new policies, and gathered to commiserate with loved ones after learning that beloved religious leaders were hiding horrible secrets. As if the monumental pain of sexual abuse alone was not horrible enough to force upon a community, the hypocrisy of these priests has sown seeds of mistrust, doubt, and fear to corners far beyond the Pittsburgh parish. Now, reports have begun to leak out that the Vatican and even Pope Francis himself may be implicated in the cover-up; facts that, if true, will only increase the waves of pain sent around the globe because of this horrendous scandal.

Although Frollo was trying to describe himself, his words in his final scene with Esmeralda ironically fit the victims of moral hypocrisy – both his and others’ – far better: “I bear the dungeon within me; within me there is winter, ice, despair; I have night in my soul” (Book VIII, chapter four).

Where Should Your Money Go?

We’ve all experienced pitches for donations that tugged on our heartstrings. During certain times of the year, when you walk into a supermarket, you can’t help encountering smiling, toothless young girl scouts pleading with you to buy cookies. On other occasions, you may run into firefighters who encourage you to put money into a boot to support the local fire department. On yet other occasions, you may be asked by a cashier at the department store if you’d like to donate to the Make-a-Wish foundation or the Special Olympics. I’m sure that all of us have, at one time or another, capitulated to these requests. Are we right to do so?

To be sure, a lot of good comes from charitable giving. The Make-a-Wish foundation makes lots of suffering children happy every year. The Girl Scouts provide valuable, formative experiences for young women. The good that firefighters do is quite obvious. If we are assessing the consequences of our donations to these causes, there is no doubt that our giving brings about something positive.

What’s more, donating to these causes makes us feel good because we observe firsthand the good that is done for our communities. These are people who, in many cases, we know. At the very least, these causes are closely related to people and institutions that we care about. Caring is an important component of moral motivation. What’s more, when we actually see the good that is being done with the money we’ve given, we might be more likely to give to good causes again in the future.

One question we can ask, however, is whether our money should be going to promote a modest amount of good when the same amount of money could, instead, be spent preventing a significant amount of harm. Consider, for example, that delicious box of thin mints that you bought from an adorable girl scout. Recently the price of girl scout cookies went up from around $4.00 to around $5.00. On its website, the Girl Scouts proudly advertises that, “100 percent of the money stays local! That means you’re not only supporting girls’ success, but the success of your community too—sweet!” Individual troupes have the option to donate the money earned by individual camps back to the troupe or to donate it to another worthy cause. The values that The Girl Scouts are trying to instill in young members are laudable. Scouts are being taught the importance of good decision-making, goal setting, money management, people skills, and business ethics. If The Girl Scouts as an organization is effective in its endeavors, young girls develop crucial virtues and, ideally they spread those virtues to other members of society as they develop into citizens, professionals, and parents. But is it a good thing that the money you donate is staying local?

If we are reflective about our charitable giving practices, one important question we must ask ourselves is whether it is better to spend money doing good or preventing harm. We aren’t preventing harm when we choose to buy a box of Girl Scout cookies, though we are doing good. On the other hand, another way that we could spend that same discretionary five dollars is to donate to, for example, a cause like the Against Malaria Foundation. Malaria is a preventable and treatable disease, but in impoverished nations, it is a deadly and destructive one. Ninety percent of malaria cases take place in sub-Saharan Africa. Even when people afflicted with malaria don’t die from the disease, it can have significant effects on the body, including severe cognitive impairment. A $2.50 donation to the Against Malaria Foundation provides a insecticidal bed net that can help prevent two at-risk Africans from contracting Malaria for up to a year. This means that the $5.00 we spent on buying a box of thin mints could prevent four people from being infected with malaria for a year.

One proposal we might consider is the following: as a general rule, we should focus our charitable giving on reducing and eliminating harms first. Harms should be, as far as is possible, ranked in terms of severity. Once we have dealt with the most significant harms, we can then move on to the harms that are less significant. Only when we have dealt with all of these harms can we finally move on to charitable causes that seek to provide benefits rather than to reduce harms. This kind of strategy is predicated on the idea that, in our charitable giving, we should strive to do the most good we can do, which means that we should seek to donate our discretionary funds as effectively as possible. This is a strategy endorsed by a growing group that calls themselves effective altruists. Effective altruism is a movement that maintains that charitable giving should be motivated not merely by fellow-feeling (though empathy is, of course, not discouraged), but instead by the results of careful inquiry and evidence collection on the subject of where the money could really do the most good.

This is a rational, evidence-based approach. On the other hand, some argue that important features of moral behavior and the development of virtuous character are missing when the issue is approached in this way. One lesson we can take from care ethics, for example, is that morality is a matter of developing relationships of care with others. This involves putting ourselves in a position to understand the people involved and be receptive to their needs. This is a practice that involves more than brute calculations. It involves really getting to know others. It may follow from this view that we are in a better position to care for the local Girl Scout than the malaria ridden person oversees. The care ethicist wouldn’t argue that we shouldn’t help those who are struggling in distant countries, however, they would argue that morality can’t simply be reduced to math.

Good people can all agree that charitable donation is important. We all need to ask ourselves which set of moral considerations should guide our decision making. Is a decision fully moral if it relies on rationality alone? Do we need to be emotionally invested in the causes to which we commit our resources?

The Moral Question of Ad-Blocking

A large proportion of websites and web content providers that do not charge a subscription fee or sell their content directly rely on advertising. Yet an increasingly large proportion of internet users are employing filtering software which is now able to block nearly all ad formats. Thus those using this software can access free content while blocking all advertising. Continue reading “The Moral Question of Ad-Blocking”

No Quick Study: The Ethics of Cognitive Enhancing Study Drugs

In July 2018 the journal Nature reported that the use of cognitive enhancing drugs – or CEDs – have steadily been on the rise. Colloquially referred to as “smart drugs” or “study drugs” due to their ability to enhance memory and concentration, they are properly classified as nootropics, a class of drug that contains popular CEDs like Adderall and Ritalin. While these drugs are common and often effective treatments for ADHD, university students are more and more frequently using them illicitly. There is little wonder why: university can often be exhausting, competitive, and stressful, so it is unsurprising that students would seek out a boost in cognitive power when dealing with that upcoming lengthy assignment, or studying for that difficult exam.

Nature also reports that while in the past students may have predominantly relied on the prescriptions of their friends to acquire such drugs, it is becoming significantly easier to buy them online. Any quick Google search will confirm this fact. When researching CEDs for this article, for instance, I came across many advertisements that promised cheap and effective nootropic drugs, delivered to my door in a timely fashion. For example, “Mind Lab Pro” was featured prominently at the top of my search results, a product which brands itself as the “first universal nootropic” and is “formulated to promote a healthy, peak-performing mindstate [sic] known as 100% Brainpower™.” What more could you want?

If you think that all sounds too good to be true, you might be right. As Nature reports,

Debate continues over whether the non-medical uses of prescription drugs boost brain performance. Data suggest that some people benefit from certain drugs in specific situations – for example, surgeons using modafinil – but larger population-wide studies report lesser gains, and conflicting results.

In addition to concerns about the efficacy and safety of using drugs that weren’t specifically prescribed for you, many have raised ethical concerns surrounding student use of CEDs. Putting the potential health risks aside, we can ask: is it ethically suspect to use CEDs as a student?

As is the case with many real-life moral questions, there are a number of arguments on both sides of the issue. The first concern is that using cognitive enhancing drugs to get better grades on exams and assignments constitutes a form of academic dishonesty. Some have compared the used of CEDs to the use of PEDs – namely, performance enhancing drugs – in sports: just as the use of steroids is often considered a form of cheating at sports, so, too, might we think that the use of CEDs should be considered a form of cheating at school. This is certainly how the The President’s Council on Bioethics consider the use of CEDs, which called academic accomplishments aided by the use of CEDs “cheating” at worst, and “cheap” at best.

If the use of CEDs is, in fact, cheating, then ethical considerations would certainly speak against their use. However, critics of this argument often point out that there are many popular forms of cognitive enhancers, the use of which is not considered cheating. Caffeine, for example, has noticeable cognitive benefits, but drinking a cup of coffee is not considered a form of cheating, even if being caffeinated played a crucial role in one’s academic accomplishments. Why, then, should it be any different for CEDs?

There are a couple of reasons why we might think that the use of CEDs is more morally problematic than the use of more widely accepted stimulants like caffeine. First of all, we might think that while anyone can buy coffee practically anywhere, access to CEDs is much more restricted. It might then be unfair to use CEDs: we might think that it is morally suspect to take advantage of a drug that can improve one’s cognitive performance if not everyone has the same kind of access to the drug.

However, it is undoubtedly the case that students have different levels of access to things that enhance their cognitive performance in ways that are generally not seen as problematic. For instance, the fact that I may not have to work during the school year, but you do, will no doubt put me at a cognitive advantage, given that I have more time to study, sleep, and relax. But it is not obvious that I am doing anything morally problematic by using those advantages.

A more general ethical concern with using CEDs is that using them creates an uneven playing field. As we’ve seen, one way that the playing field can become uneven is due to differences in access. The other way is the simple difference in cognitive abilities that result from the use of CEDs: it seems unfair that some people should get a boost in abilities that others do not. Again, we can see how the use of CEDs might be compared to the use of PEDs: it doesn’t seem fair that I should have to compete with someone who is using steroids in order to a get a spot on the team.

But again, there is reason to think that this kind of unfairness is not necessarily morally problematic. Here’s an argument as to why: the fact is that students are not on an even playing field with regards to their abilities regardless of their use of cognitive enhancing drugs, so the mere fact that CEDs may contribute to an uneven playing field is not in itself good enough reason to think that we shouldn’t use them. For example, say that we are both studying for an exam for a class that is built around memorization of facts from a textbook, and that your memory is significantly better than mine. We are clearly playing on an uneven field, but there is nothing morally problematic about you using the superior abilities that you have. Again, this is just one example out of potentially many: cognitive abilities amongst students may vary significantly, but this kind of unevenness does not seem to entail any particular ethical concerns.

Finally, one might worry that successes aided by the use of CEDs do not constitute genuine academic achievements, either because of the above concerns about cheating or using an unfair advantage, or because such accomplishments are not truly due to the abilities of the students themselves. We might think that in order for one’s accomplishments to have value, or to contribute to the strength of one’s character, that they should be solely the product of the individual, and not the individual on drugs. For example, consider a runner who wins a race, but only because they had a particularly strong gust of wind behind them the entire time. We would probably diminish their accomplishment somewhat, because we might think it wasn’t really them that was fully responsible for winning. Similarly, we might think that the continuous reliance on CEDs is a sign of poor character: we would not think that a runner who only ran races with a strong tailwind were particularly virtuous runners.

There is one more general ethical concern about the prevalence of CED use, namely that widespread use risks establishing a new status quo. As Nicole Vincent and Emma Jane at The Conversation argue, with increased CED use and acceptance we might create a future in which such use becomes expected – i.e. that the nature of certain types of employment will become such that they can only be performed in a satisfactory way if one uses cognitive enhancers – but also that one might be held responsible for failing to use CEDs when doing so would improve their results (Vincent and Jane provide an example of a surgeon whose focus could be enhanced by used of CEDs, and could be found negligent if they choose not to use them).

Proponents of CED use, however, might not find such consequences to be particularly troubling. Indeed, just as coffee consumption has become commonplace and accepted, so too might the use of CEDs. And if there’s nothing wrong with having a morning cup of coffee, then what’s wrong with having your morning Ritalin?

The debate over the ethical implications of CEDs, then, is messy. Regardless of the kinds of arguments you find most convincing, though, it seems clear that, in addition to general health concerns about using drugs that weren’t prescribed to you, that there are significant ethical concerns that one needs to consider before attempting to achieve anything approaching “100% Brainpower”.

Insider Talk: Challenging Food Choices

When a company wants to go green, are there limits on what it can ask of its employees? This question came to the fore due to WeWork’s recent announcement: the company will no longer serve or reimburse for meat, citing the environmental costs of animal protein and, to a lesser extent, worries about animal welfare. The reaction was swift and negative: it’s just virtue signaling, it’s an ideological crusade, it’s tribalism, it’s bull. The North American Meat Institute, a lobbying group for the industry — has even launched IChooseMeat.com, a response to the threat of “your office dictating your food choices,” and which aims to “fight meat denial.”

Here, though, I don’t want to get lost in the criticisms of WeWork’s policy, both because they seem like overreactions, and because they seem misguided in an era that expects moral leadership in business. They are overreactions because such policies don’t force anyone to do anything. You want to eat meat? Go for it. Just don’t expect your company to subsidize it. Was it any worse for companies to remove cigarette machines from their offices in the 80s, when smoking was still commonplace? And they are misguided because this sort of disagreement is the price of something that’s genuinely good: namely, having companies care about more than profits. We have long wanted businesses to be more socially conscious, but of course we disagree about what being “socially conscious” involves. These conflicts aren’t bugs in the new order: they’re features, and ones to which we should acclimate ourselves.

So let’s set those issues aside. Instead, let’s focus on the general puzzle here. Why do we bristle when people challenge our meat consumption? And is our bristling justified?

There are, of course, those who don’t like the challenge because they’re climate change skeptics, or they don’t think it matters at all whether animals suffer, or what have you. But if one of those factors explains the negative reaction, then the disagreement is probably too deep to resolve, and we should simply move on.

There are a slew of other uninteresting possibilities. For instance, we don’t like being made to feel guilty about food. (But who likes it in other contexts?) And you sometimes hear people say that change is hard. (Not much defense: we can always play that card.) Ultimately, though, I think we need a more interpersonal story. We don’t seem to think that people have the right to criticize what we eat. And why would that be? What norm are they violating?

A few possibilities come to mind. The first is that this is somehow a violation of privacy. But if that’s what’s bothering us, it won’t go far as a justification. It’s one thing to claim that a matter is private when it has no public consequences. But our diets do, and so they seem subject to public scrutiny.

A second option is a “local knowledge” objection. Maybe no one knows a person’s situation well enough to decide what he or she ought to eat. Only you know whether you need some chicken to flourish, or if you can make it just fine on garbanzo beans. But again, this seems implausible as a defense. I don’t know much at all about what my body needs; I just know what makes me feel good. And feeling good is as much about habit and history as it is about biology: I feel a certain way in response to whether I’m getting what I want (cake), not whether I’m fueling in the optimal way (spinach and lentils).

A third story is that we’re not open to moralizing about food, as we care too much about it. This is a bit like the way that having children is awful for the environment, but we don’t stop having them for that reason. The environment matters to us, but not that much. However, the parallel isn’t great. The impulse to have children runs deep, and for many people, their kids make their lives meaningful. Of course, food is also tied to living meaningfully: table fellowship is among life’s basic pleasures, and can forge deep bonds. However, you can savor time with family without eating turkey. This requires flexibility, but not the rejection of one of our deepest longings.

A final possibility — and the one I find most plausible — is that food talk is insider talk. Debates about what we eat, like debates about sex and child rearing, are ones we have with those who aren’t in our tribe — with non-Christians or non-liberals or non-crunchy moms — but we generally don’t change our minds as a result. By contrast, if a fellow liberal expresses worries about prostitution, or if your pastor gives you an argument against spanking your kids, you might well see things differently. You trust insiders to see the world in roughly the way you do, and as a result, their reasoning gets extra weight in your own deliberations.

If this is what’s going on, it’s both understandable and unfortunate. The former, because ethics is hard, disagreement is everywhere, and we need some strategy for deciding how to allocate our limited time and attention. After all, moral conversation isn’t the whole of life; at some point, you have to do the dishes and the laundry.

It’s unfortunate, though, because of what it implies about the way people insulate ourselves from moral criticism. There are things for which it’s worth circling the wagons. But food? In his Meditations, Marcus Aurelius observed that “all through our lives when things lay claim to our trust,” we should strive to see them clearly, “stripping away the legend that encrusts them.” Food is full of legends, but it’s ultimately just sustenance. It’s a mean to many ends — nutritionally, socially, politically — though ones that can usually be achieved in other ways. It isn’t sacrosanct, and change, though difficult, is possible.

So should everyone become a strict vegetarian? Maybe, maybe not. But the conversation is worth having.

What’s the Story with Fake News?

Every day U.S. President Donald Trump calls “fake news” on particular stories or whole sections of the media that he doesn’t like. At the same time there has been a growing understanding, inside and outside the U.S., that “fake news”, that is to say fabricated news, has in recent years had an effect on democratic processes. There is of course a clear difference between these two uses of the term, but they come together in signifying a worrying development in the relations of public discourse to verifiable truth.

Taking the fabricated stories first – what might be called “real fake news” as opposed to Trump’s “fake fake news” (to which we shall return) – an inquiry concluded by the UK parliament in recent weeks that sheds further light on the connections between lies and disinformation, social media, and hindrance of transparent democratic processes makes sobering reading.

On July 24 the British House of Commons Digital, Culture, Media and Sport (DCMS) Committee released its report on ‘disinformation and fake news’. What began as a modest inquiry into recent developments and trends in digital media “delved increasingly into the political use of social media” and grew in scope to become the most detailed look yet to be published by a government body at the use of disinformation and fake news.

The report states that

“…without the knowledge of most politicians and election regulators across the world, not to mention the wider public, a small group of individuals and businesses had been influencing elections across different jurisdictions in recent years.”

Big Technology companies, especially social media companies like Facebook, gather information on users to create psychographic profiles which can be passed on (sold) to third parties and used to target advertising or fabricated news stories tailored to appeal to that individual’s beliefs, ideologies and prejudices in order to influence their behavior. This is a form of psychological manipulation in which “fake news” has been used with the aim of swaying election results. Indeed, the DCMS committee thinks it has helped sway the Brexit vote. Other research suggests it helped to elect Donald Trump in the 2016 U.S. presidential Election.

The report finds that

“…urgent action needs to be taken by the Government and other regulatory agencies to build resilience against misinformation and disinformation into our democratic system. Our democracy is at risk, and now is the time to act, to protect our shared values and the integrity of our democratic institutions.”

It’s not easy to define what “fake news” is. The term is broad enough to include lies, misinformation, conspiracy theories, satire, rumour or stories that are simply wrong. All these categories of falsehood have been around a long time and may not necessarily be malicious. The epistemic assumption that the problem with fake or misleading news is that it is untrue is not always warranted.

Given that information can be mistaken yet believed and shared in good faith, an evaluation of the epistemic failings of false information should perhaps be judged on criteria that include the function or intention of the falsehood and also what is at stake for the intended recipient as well as the purveyor of misinformation. In other words, the definition of fake news should include an understanding of its being maliciously produced with the intention to mislead people for a particular end. That is substantively different from dissenting opinions or information that is wrong, if disseminated or published in good faith.

The DCMS report recommended dropping the term “fake news” altogether and adopting the terms ‘misinformation’ and/or ‘disinformation’. A reason for this recommendation is that “the term has taken on a variety of meanings, including a description of any statement that is not liked or agreed with by the reader.”

The ethical dimensions of fake news seem relatively uncomplicated. Though it is sometimes possible to make a moral case for lying – perhaps to protect someone from harm, for fake news there is no such case to be made, and there is little doubt that its propagators have no such reasoning in mind. We don’t in general want to be lied to because we value truth as a good in itself; we generally feel it is better for us to know the truth, even if it is painful, than not to know it.

The thorny ethical problems arise around the question of what, if anything, fake news has to do with freedom of speech and freedom of press when calls for regulation are on the table. One of the greatest justifications for free speech was put forward by the liberal philosopher John Stuart Mill. Mill thought that suppression of error (by a government) could never rule out accidental (or even deliberate) suppression of truth because we are not epistemically infallible. The history of knowledge is, after all, a history of having very often to correct grave and, sometimes, ludicrous error. Mill convincingly argued that unrestricted discussion allowed truth to flourish. He thought that a “clearer perception and livelier impression of truth [is] produced by its collision with error.”

However, on closer consideration, free speech may not really be what is at stake. Mill’s defense of free press (free opinion) ends where ‘in good faith’ ends, and fake news, as wielded by partisan groups on platforms like Facebook, is certainly not in good faith. Mill’s defense of free and open discussion does not include fake news and deliberate disinformation, which is detrimental to the kind of open discussion Mill had in mind, because rather than promote constructive conversation it is designed to shut conversation down.

Freedoms are always mitigated by harms: my freedom to swing my fist around ends where your nose begins. And the DCMS report is one of numerous recent findings that show the harms of fake news. Even if we grant that free speech doesn’t quite mean freedom to lie through one’s teeth (and press / media doesn’t quite mean Facebook) it still is not easy to come up with a regulatory solution. For one thing, regulations can themselves be open to abuse by governments – which is precisely the kind of thing Mill was at pains to prevent. The term “fake news” has already become a tool for political oppression in Egypt where “spreading false news” has been criminalized in a law under which dissidents and critics of the regime can be, and have already been, prosecuted.

Also, as we grapple with the harms caused by deliberate, targeted misinformation, the freedom of expression question dogs the discussion because social media is, by design, not a tightly controlled conversational space. It can be one of the internet’s great benefits that it has a higher degree of freedom than traditional media — even if that means a higher degree of error. Yet it is clear from the DCMS report that social media “platforms” such as Facebook are culpable, if not legally (since Facebook is at present responsible for the moderation of its own content), then ethically. The company failed to prevent use of its platform for targeted and malicious campaigns of misinformation, and failed to act once it was exposed.

Damian Collins, the Conservative MP for Folkestone and chair of the DCMS committee, spoke of “Facebook’s complete lack of moral responsibility”; the “disingenuous” responses from its executives, and its determination to “time and again… avoid answering… questions to the point of obfuscation”. Given that attention-extraction companies like Facebook are resistant to change because it is against their business model, democratic governments and regulators will have to consider what measures can be taken to mitigate the threats posed by social media in its role in targeted dissemination of misinformation and fake news.

At stake in the problem of fake news is the kind of conversational space necessary for a healthy functioning society. Yet the ‘”fake fake news” of President Donald Trump is arguably more insidious, and perhaps even harder to inoculate against. In what can only be described as an Orwellian twist in the story of fake news, Donald Trump throws the term at the mainstream media even as they report something much more answerable to epistemic standards of truth and fact than the fabricated stories propagated through social media or the transparent lies Trump himself so effortlessly dispenses.

Politicians have long had a reputation for demagoguery and spin, but Trump’s capacity to lie in the face of manifest reality (inauguration crowd size just for one obvious example) and to somehow ‘get away with it’ (at least to his supporters) is extraordinary, and signals a deep fissure in the relation between truth, trust, and civic discourse.

To paraphrase Australian philosopher Raimond Gaita: to deride the serious press as peddling fake news, to deride expertise that proves what justifiably can count as knowledge, is to undermine the conceptual and epistemic space that makes conversations between citizens possible.

J. S. Mill’s vision for a society in which, despite and sometimes through error, truth can be discovered, and where it has an epistemic priority in establishing trust as a foundation for a liberal, democratic life is lost in the contempt for knowledge and truth that is captured in the idiom of this “post-truth” era.

Both senses in which “fake news” is now pervading our civic conversational space threaten public discourse by endangering the very possibility of truth and fact being able to guide, ground and check public discourse. Big Technology and social media have no small part to play in these ills.

An epistemic erosion is underway in public discourse which undermines the conversational space – that space that Mill thought was so important for the functioning of a free society – which allows citizens to grapple with self-understanding and to progress towards more just and better forms of civic life.

Crisis in Sweden: A Struggle with Mass Migration

In 2015, the year of the Syrian refugee crisis, Sweden accepted over 160,000 refugees, more refugees per capita than any other European nation. The sparsely-populated country prides itself on its generosity towards newcomers, and Sweden’s foreign minister even declared the country to be a “humanitarian superpower.” Years later, Sweden continues to be one of two European nations (the other being Germany) to have opened its borders to such a drastic extent, having accepted approximately three out of every four asylum seekers in 2015. Continue reading “Crisis in Sweden: A Struggle with Mass Migration”

Sip Carefully: Plastic Straws and the Individualization of Responsibility

This article has a set of discussion questions tailored for classroom use. Click here to download them. To see a full list of articles with discussion questions and other resources, visit our “Educational Resources” page.

In 2015 a video of a sea turtle took the internet by storm and set into action the public outrage over pollution caused by plastic straws. Since then, videos and articles including facts about plastic waste in the world’s oceans have been circulating the internet, and plastic pollution has been the topic of more than a few TED Talks. Many anti-plastic advocates made moral appeals to consumers to cut down on their straw usage, and these appeals have steadily grown into an anti-straw environmental movement. On July 9th, coffee mogul Starbucks announced they would be phasing out plastic straws in their cafes nationwide, eliminating plastic straws completely by 2020. However, it did not take long for the blowback to come. New videos and articles began circling social media, this time depicting people with disabilities explaining how the plastic straw ban in businesses, and cities like Seattle and San Francisco makes them feel unwelcome. Is banning plastic straws, like Starbucks did, really an ethical environmental choice? Should the responsibility be on companies or consumers to reduce plastic usage? And do appeals to morality through social media campaigns and public outrage truly effectuate positive change? Continue reading “Sip Carefully: Plastic Straws and the Individualization of Responsibility”

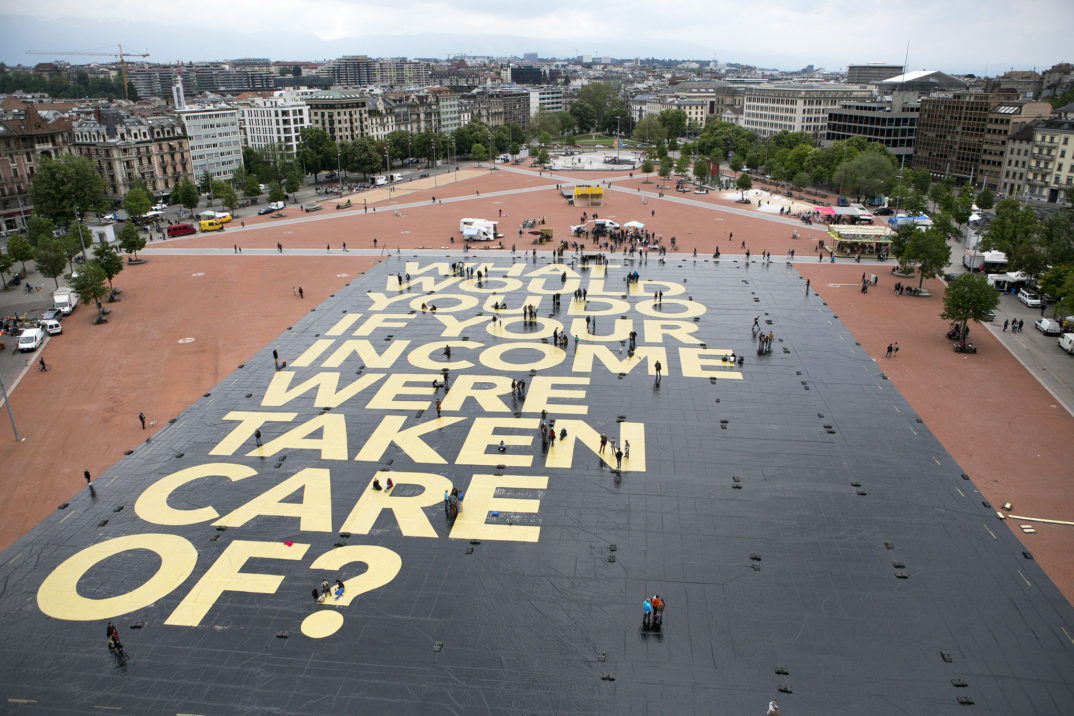

The Right Side of History: A Case for Basic Income

Doug Ford’s recently elected Conservative government has announced withdrawal of a province-wide basic income pilot that they had pledged to maintain during their campaign. Many see this basic income project not only as a lifeline for struggling workers, but the future of redistribution under late capitalism. Continue reading “The Right Side of History: A Case for Basic Income”

Spilled Blood in the Bloodline: The Ethics of Using Genealogy to Catch Criminals

On April 24th 2018, authorities arrested 72- year-old Joseph James DeAngelo. Investigators had compelling evidence to suggest that DeAngelo committed at least 12 murders, 50 rapes, and over 100 burglaries throughout California in the 70s and 80s, earning him the monikers “The East Area Rapist” and “The Golden State Killer.” DeAngelo might have lived out his life without being caught were it not for the existence of a genealogy website.

Continue reading “Spilled Blood in the Bloodline: The Ethics of Using Genealogy to Catch Criminals”

Affirmative Action and A Medical University’s Attempt at No Girls Allowed

On Friday, August 3rd, the Japanese government urged Tokyo Medical University to uncover the results of their investigation into allegations that the entrance exams of women were altered to prevent them from qualifying as applicants. In 2010, successful female applicants reached 38 percent and sources report that efforts began to reduce this increase in potential female doctors, resulting in 10% of successful exam scores being lowered.

Japan’s prime minister, Shinzo Abe, has an economic platform that touts equality, with a focus on improving women’s place in the workforce. With initiatives that together have been dubbed “womenomics”, Abe’s policies have been praised as beginning “a new era in female success.” He aimed to achieve gender equality in the workforce by 2015. Currently, 3.7% of executives of Japanese companies are women, 73% of Japanese companies have no women at the management level, and 57.7% of women are engaged in “non-regular” employment. A new era is badly needed because Japan has been sliding down the World Economic Forum’s world ranking of the gender gap. In 2008, it ranked 80th, but it was down to 111th in 2017 and 114th in 2017. This slipping has brought skepticism to the effectiveness of Abe’s womenomics initiatives.

It is an uphill battle to reverse the gender issues in the workforce when Members of Parliament publicly claim that single women are a burden on the state and should be producing more children. Yet it was the sexist conception of women as worse candidates because of their association with family responsibilities that was the very prejudice cited as motive behind Tokyo Medical University’s application falsifications.

The difficulties in meeting the goals of workforce equality has made Abe revise his goals this year: “In 2016 the government revised an ambitious national target of filling 30% of senior positions in both the public and private sectors with women by 2020. The new targets were 7% for senior government jobs and 15% at companies.” Setting such goals and quotas is controversial, and some executives and government officials worry that these policies may increase the “quantity” of women in the workforce while allowing the “quality” to decrease.

The concerns with setting goals to increase representation in the workforce or universities are not new, and invoke the debate over strategies of affirmative action. “Affirmative action” refers to steps taken to increase the representation of marginalized groups, either in university systems, government, or the workplace.

In 1965 in the US, the Civil Rights Act included affirmative action language that barred companies, unions, or other institutions from discriminatory practices. In particular, the Department of Labor put into place regional numerical goals to increase fair representation in the workforce.

The use of gender and racial preferences in hiring and admissions is, of course, controversial. In their favor is the consideration that giving marginalized groups preference is just, given these groups’ previous exclusion: this preference rights the harm, therefore evening the playing field. This consideration has been attacked because the wrong is systemic but the redress individual. In other words, someone could get preferential treatment who may not have faced discrimination themselves in their individual life.

Further, this preferential treatment may come at the cost of the non-preferred groups who are not responsible for the systemic problems faced by the marginalized groups. We could think of the harm in terms of an applicant or employee receiving “less consideration,” or in terms of not getting their right (if there is one) to “equal consideration”. Thus, appeals to justice, rights, and harms can be brought out both in favor of bringing race and gender into play when making workplace and university choices as well as leaving them out.

However, the very pervasiveness of privilege given to white people and men is often cited as justification for giving preferential treatment to the less privileged. James Rachels and Mary Anne Warren point to the likelihood that non-marginalized individuals have benefited or would benefit from their privileged positions as justification to use preferential practices as a way of neutralizing this imbalance. This can be taken to mitigate the concern about the systemic versus individual level of harm and reparation.

The use of race and gender as criteria for employment and admission seems to some to be problematic in principle, whether used to increase or decrease an applicant’s favorability. For instance, Lisa Newton’s objection to affirmative action is that it uses race and gender to distinguish among people, which is what was objectionable in creating conditions of marginalization in the first place: “Just as the previous discrimination did, this reverse discrimination violates the public equality which defines citizenship” (Newton 1973, 310).

In practice in the US, affirmative action in the workforce has been implemented since the ‘70s in order to be in line with anti-discrimination policies — rather than on the justification of righting past wrongs, offsetting unfair advantages, appropriately rewarding the deserving, or producing some social goods. Instead, the preferential treatment righted the discrimination that would continue from practices that were permissible before the Civil Rights Movement.

The quotas and goals that Abe and his policies aim towards in Japan would impact the workforce considerably. Expectations of women and men have varied significantly and the efforts to close the gender gap would have far reaching effects (some estimate increasing women’s presence in the workforce would increase Japan’s GDP by 13%). Preferential hiring practices may be one tool in altering the workforce’s landscape, but there are social features that also need to be dealt with.

In 2016, while the percentage of men and women with university degrees did not vary significantly (59% of women and 52% of men), the family and household responsibilities certainly did: women completed an average of 4.26 hours of housework a day versus 1.38 hours completed by men, and while women spent an average of 7.57 hours with children, men spent less than half that much (3.08 hours). Japan faces a childcare crisis, making it difficult to lighten the household responsibilities on women and allow them in the workforce.

The underlying attitudes about the roles of women loom large in the efforts to close the gender gap in the workforce as well as Tokyo Medical University’s recent efforts to keep that gap in place in medicine. A key tool to deal with a history of discriminatory practices has been affirmative action, preferential weighing of marginalized groups in order to reach some desired level of representation. The effectiveness of this tool and the grounds of justifying the preferential treatment come with difficult questions of equality and distributive justice. Policies themselves won’t change bigoted attitudes, of course, and perhaps ideally gender and race wouldn’t be parameters that would matter in hiring practices. They demonstrably affect a person’s outcome in the workforce, however, and have throughout history.

Bad Tweets and the Ethics of Shaming

Here’s a news story that you’ve probably come across recently: someone’s tweets from a number of years ago have resurfaced, and they’re not good. Tweets that express racist, sexist, homophobic, or whatever other kinds of reprehensible sentiments are brought to light, and the original tweeter is publicly shamed, in one form or another. Making the biggest headlines recently is undoubtedly James Gunn, director of the first two Guardians of the Galaxy movies: Gunn was fired from directing the next installment of the blockbuster franchise due to the discovery of old tweets in which he made a series of tasteless jokes about rape and pedophilia. Or consider two recent examples from the world of professional baseball: the cases of Atlanta Braves pitcher Sean Newcomb and Washington Nationals shortstop Trea Turner, whose Twitter histories were rife with posts using homophobic slurs. The punishments that the Tweeters received upon discovery of their tweets has varied significantly: in Gunn’s case, losing his job, while in Newcomb’s and Turner’s cases, having to issue statements expressing their remorse.

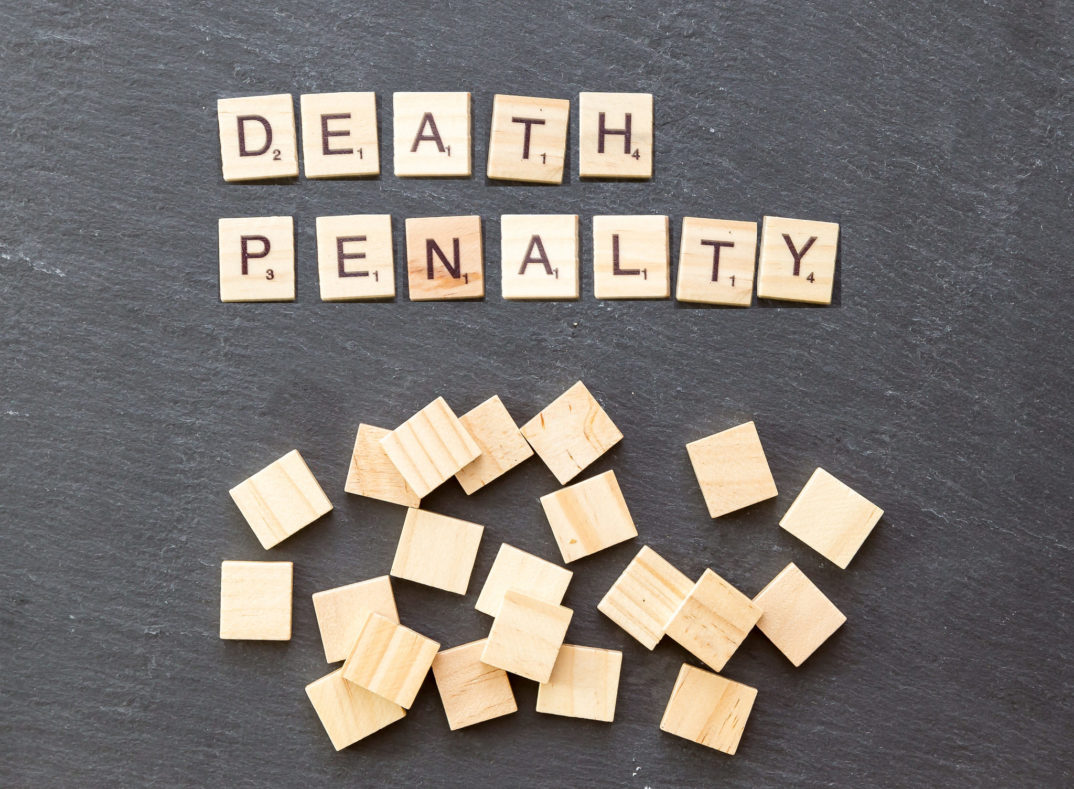

Human Dignity, Capital Punishment, and the Pope

Since his elevation to the papal seat in 2013, Pope Francis has repeatedly made international headlines with comments suggesting a desire to change Roman Catholic doctrine on matters ranging from marriage to contraception to the nature of the afterlife and more. The beginning of August saw Francis make more than a remark with the publication of a revision to the Catechism of the Catholic Church officially labeling the death penalty “inadmissible” in all cases.

Continue reading “Human Dignity, Capital Punishment, and the Pope”

Reframing Picasso: Hannah Gadsby and “Separating the Man from the Art”

“High art elevates us and civilizes people,” the Australian comedian Hannah Gadsby claims, jokingly presenting an observation from her art history degree. “Comedy, lowbrow. I am sorry to inform you, but nobody here is leaving this room a better person.” When she delivered this joke, most of the audience probably did not detect the irony, because who would expect to leave a comedy show with a new glimpse at humanity? Those discussions are usually saved for the art museums. Continue reading “Reframing Picasso: Hannah Gadsby and “Separating the Man from the Art””

Ethical Concepts in the Age of the Anthropocene

This article has a set of discussion questions tailored for classroom use. Click here to download them. To see a full list of articles with discussion questions and other resources, visit our “Educational Resources” page.

We all know, more or less, that Planet Earth is in trouble, that there is an overwhelming scientific consensus that an environmental catastrophe — systemic, complex, and more and more irreversible — is already underway.

We are facing an unprecedented concatenation of changes to the Earth. Global warming from fossil fuel pollution is causing ice caps to melt and oceans to rise, threatening to inundate many coastal habitats within decades. Climate change is causing more frequent and more extreme weather events in the form of violent storms and severe droughts. Destruction of ecological systems is leading to the collapse of insect and bird populations which are necessary for the pollination of plants including human food crops. Oceans are filling up with plastic waste, and toxic synthetic substances can now be found in every part of the world. A “biological annihilation” of wildlife in recent decades shows that the sixth mass extinction in Earth’s history is underway and it is more severe than previously feared, according to new research.

Continue reading “Ethical Concepts in the Age of the Anthropocene”