Blaming the Blasphemer

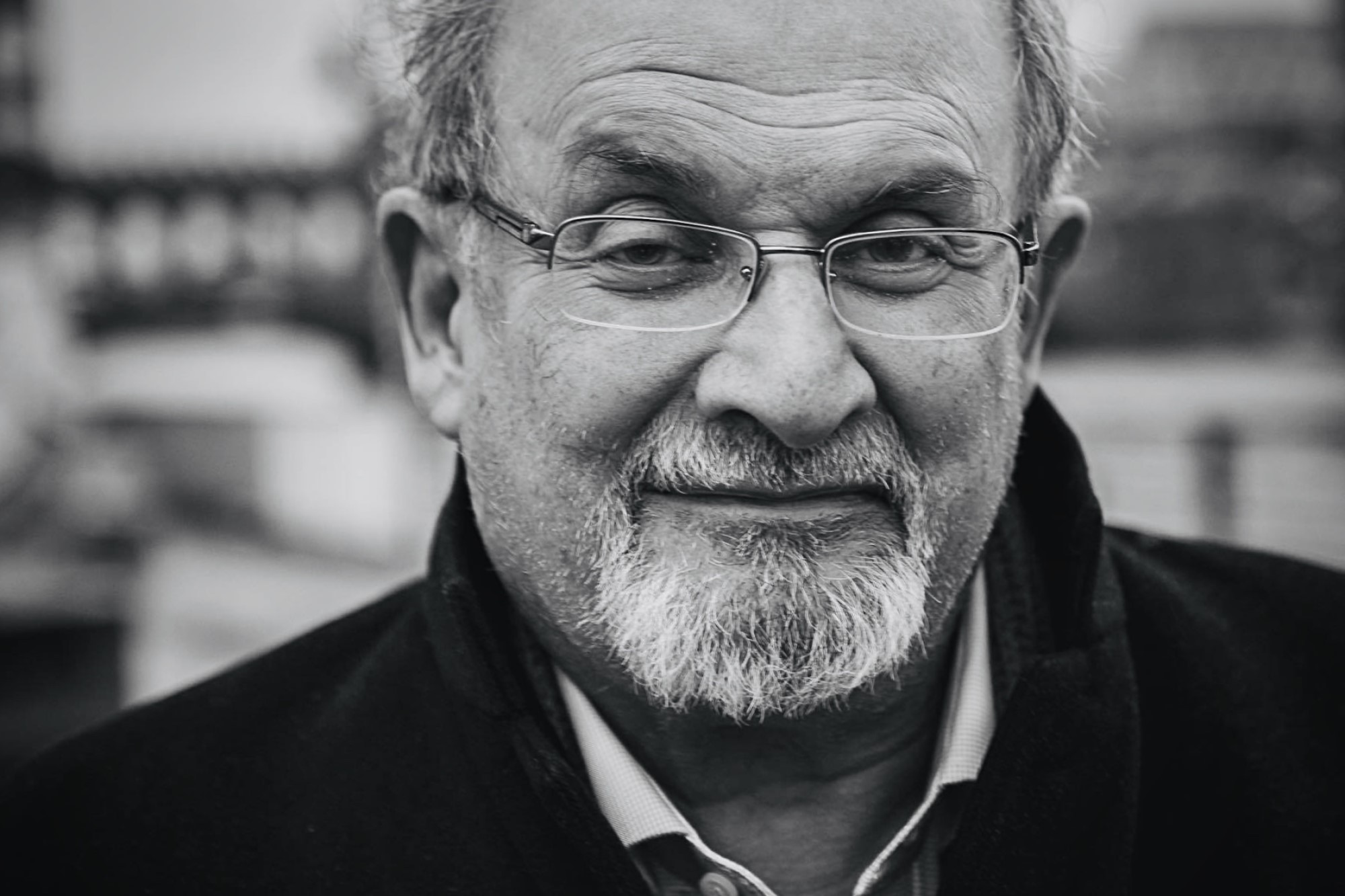

As I write, Salman Rushdie is in hospital on a ventilator, having been stabbed in the neck and torso while on stage in New York. His injuries are severe. It is, at this moment, unknown if he will survive.

Rushdie’s novel The Satanic Verses, a work of fiction, is considered blasphemous by many Muslims, including the late Ayatollah Khomeini. For those who don’t know, the Ayatollah issued a public fatwa (religious judgment) against Rushdie, calling for all Muslims to kill him and receive a reward of $3,000,000 and immediate passage to paradise. The cash reward was recently raised by $600,000, though the Iranians seem to have struggled to improve on the offer of eternal paradise.

In 1990, Rushdie attempted to escape his life in hiding. He claimed to have renewed his Muslim faith of birth, stating that he did not agree with any character in the novel and that he does not agree with those who question “the authenticity of the holy Qur’an or who reject the divinity of Allah.” Rushdie later described the move as the biggest mistake of his life. In any case, it made no difference. The fatwa stood. “Even if Salman Rushdie repents and becomes the most pious man of all time,” Khomeini stated, “it is incumbent on every Muslim to employ everything he has got, his life and his wealth, to send him to hell.”

There are now reports of celebration in Tehran. “I don’t know Salman Rushdie,” Reza Amiri, a 27-year-old deliveryman told a member of the Associated Press, “but I am happy to hear that he was attacked since he insulted Islam. This is the fate for anybody who insults sanctities.” The conservative Iranian newspaper Khorasan’s headline reads “Satan on the path to hell,” accompanied by a picture of Rushdie on a stretcher.

Rushdie is not the only victim of the religious backlash to his novel. Bookstores that stocked it were firebombed. There were deadly riots across the globe. And others involved with the publication and translation of the book were also targeted for assassination including Hitoshi Igarashi, the Japanese translator (stabbed to death), Ettore Capriolo, the Italian translator (stabbed multiple times), the Norwegian publisher William Nygaard (shot three times in the back outside his Oslo home), and Aziz Nesin, the Turkish translator (the intended target of a mob of arsonists who set fire to a hotel, brutally murdering 37 people).

These attacks, including the latest on Rushdie, and the issuing of the fatwa are all very obviously morally reprehensible. But there is perhaps a bit more room for discussion when it comes to the choice of Rushdie to publish his novel.

Is it morally permissible to write and publish something that you know, or suspect, will be taken to be blasphemous, that you think will result in the deaths of innocents?

At the time of the original controversy, this question divided Western intellectuals.

Western critics of Rushdie included the Archbishop of Canterbury, Prince Charles, John le Carre, Roald Dahl, Germaine Greer, John Berger, and Jimmy Carter. “Nobody has a God-given right to insult a great religion and be published with impunity,” wrote le Carre, calling on Rushdie to withdraw the book from publication.

In The New York Times, Jimmy Carter wrote: “Rushdie’s book is a direct insult to those millions of Moslems whose sacred beliefs have been violated.” Rushdie, Carter contended, was guilty of “vilifying” Muhammad and “defaming” the Qur’an. “The author, a well-versed analyst of Moslem beliefs,” complained Carter, “ must have anticipated a horrified reaction through the Islamic world.” John Berger, author, Marxist, and literary critic, provided a similar condemnation of Rushdie and his publishers in The Guardian, noting that his novel “has already cost several human lives and threatens to cost many, many more.” Roald Dahl, the well-loved children’s book writer, concurred: “he must have been totally aware of the deep and violent feelings his book would stir up among devout Muslims. In other words, he knew exactly what he was doing and he cannot plead otherwise.”

These intellectuals’ central contention was that Rushdie had acted immorally by publishing the book and thereby causing unnecessary loss of life.

(Both Carter and Berger also offered clear condemnations of both the violence and the fatwa.)

A peculiar thing about this critique is that Rushdie never attacked anyone. Other people did. And these murders and attempted murderers were not encouraged by Rushdie, nor were they acting in concordance with Rushdie’s beliefs or wishes. The criticism of Rushdie is merely that his actions were part of a causal chain that (predictably) produced violence, ultimately on himself.

But such arguments look a lot like victim-blaming. It would be wrong to blame a victim of sexual assault for having worn “provocative” clothing late at night. “Ah!” our intellectual might protest, “But she knew so much about what sexual assaulters are like; it was foreseeable that by dressing this way she might cause a sexual assault to occur, so she bears some responsibility, or at least ought not to dress that way.” I hope it is obvious how feeble an argument this is. The victim, in this case, is blameless; the attacker bears full moral responsibility.

Similarly, it would be wrong to blame Rushdie for having written a “provocative” work of fiction, even if doing so would (likely) spark religious violence. The moral responsibility for any ensuing violence would lie squarely at the feet of those who encourage and enact it.

It is not the moral responsibility of an author to self-censor to prevent mob violence, just as it is not the moral responsibility of a woman to dress conservatively to prevent sexual assault on herself or others.

“I do not expect many to listen to arguments like mine,” wrote Rushdie-critic John Berger, a bit self-pityingly (as Christopher Hitchens noted) for one of the country’s best-known public intellectuals writing in one of the largest newspapers in Britain, “The colonial prejudices are still too ingrained.” Berger’s suggestion is that Rushdie and his defenders are unjustifiably privileging values many of us find sacred in the West — such as free expression — over those found sacred in the Muslim world.

But there is another colonial prejudice that is also worth considering; the insulting presumption that Muslims and other “outsiders” have less moral agency than ourselves. According to this prejudice, Muslims are incapable of receiving criticism or insult to their religion without responding violently.

This prejudice is, of course, absurd. Many Muslims abhor the violent response to The Satanic Verses and wish to overturn the blasphemy laws which are so common in Muslim-majority countries. It is an insult to the authors who jointly wrote and published For Rushdie: Essays by Arab and Muslim Writers in Defense of Free Speech. It denies the 127 signatures of imprisoned Iranian writers, artists, and intellectuals who declared:

We underline the intolerable character of the decree of death that the Fatwah is, and we insist on the fact that aesthetic criteria are the only proper ones for judging works of art. To the extent that the systematic denial of the rights of man in Iran is tolerated, this can only further encourage the export outside the Islamic Republic of its terroristic methods which destroy freedom.

Rushdie’s critics, keen as they were to protect a marginalized group, condemned Rushdie for causing the violence committed by individual Muslims. But in doing so, these intellectuals treated the Muslim perpetrators of that violence as lacking full moral agency. You can’t cause autonomous people to do something – it is up to them! Implicitly, Rushdie’s Western critics saw Muslims as mere cogs in a machine run by Westerners, or “Englishmen with dark skin” such as Rushdie, as feminist Germaine Greer mockingly referred to him. Rushdie’s critics saw Muslims as less than fully capable moral actors.

True respect, the respect of moral equals, does not ask that we protect each other from hurt feelings. Rather, it requires that we believe that each of us has the capacity to respond to hurt feelings in a morally acceptable manner – with conversation rather than violence. In their haste to protect a marginalized group, Rushdie’s critics forgot what true respect consists of. And in doing so, they blamed the victim for the abhorrent actions of a small number of fully capable and fully responsible moral agents. This time around, let’s not repeat that moral mistake.