White Skins, Black Masks: Voice Acting and Representation

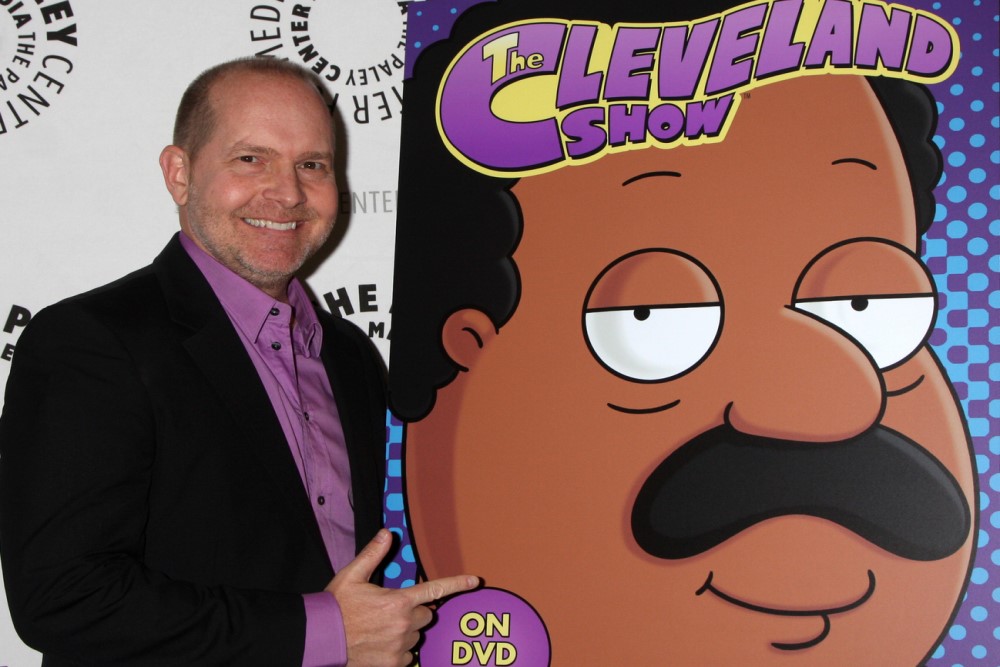

On June 26, 2020, the creators of The Simpsons announced that from now on, white actors will no longer voice the show’s non-white characters. This came a few days after Kristen Bell, Jenny Slate, and Mike Henry said that they would no longer voice characters of color on their respective shows. “Missy [a character voiced by Slate on the Netflix animated comedy Big Mouth] is Black,” Slate wrote on Instagram. “[A]nd Black characters on an animated show should be played by Black people.” Thus, there appears to be a growing belief in the ethical principle that only people of color are permitted to voice animated characters of color. Call this the Exclusive Principle.

The argument most frequently advanced for the Exclusive Principle concerns the underrepresentation of actors of color in the entertainment industry. Thus, NPR’s Eric Deggans writes that casting white actors as non-white characters “has the practical effect of reinforcing Hollywood’s damaging tendency to elevate…white performers over people of color.” There is no question that this is a serious problem: for example, while people of color make up 40% of the U.S. population, they comprise only 14% of directors, 13.9% of writers, and 32.7% of actors. But the argument for the Exclusive Principle is that following it is either sufficient or necessary to increase the representation of actors of color, and this may be doubted. To see this more clearly, consider an animated television show in which there are twenty characters, nineteen of whom are white while one is a person of color. All nineteen white characters are voiced by actors of color, while the sole person of color is voiced by a white actor. While this television show violates the Exclusive Principle, it appears to do well with respect to employing actors of color. By contrast, another television show that employs a person of color to voice its sole character of color but white actors for every other role satisfies the Exclusive Principle, but does not do well with respect to representation. Thus, following the Exclusive Principle is neither necessary nor sufficient for significantly increasing representation.

A reasonable reply is that following the Exclusive Principle would still typically have the effect of increasing representation. That may well be true. But it is also possible that only allowing people of color to voice animated characters of color is not the most effective way of employing more actors of color in animation. A better way may be to simply cast more actors of color to voice both characters of color and white characters. On the other hand, while this might theoretically be a better way of increasing representation, it might also be the case that following the Exclusive Principle is easier in practice than fulfilling this more demanding policy of casting more actors of color to voice both white and non-white characters. Since there are fewer characters of color in animated series overall, following the Exclusive Principle as a means to increase representation would require fewer ‘affirmative’ casting choices. And if showrunners are more likely to follow a policy entailing fewer such choices, then it may turn out that following the Exclusive Principle will increase representation more effectively than the more demanding policy.

In any case, my hunch is that many of those who subscribe to the Exclusive Principle would still object to the television show in which actors of color are well-represented but the sole character of color is voiced by a white actor. But this means they must have some reason for supporting the Exclusive Principle that is distinct from the representation argument. At first sight, the notion that white actors should not voice animated characters of color is a logical extension of the prohibition on black-, brown-, or yellow-face: if white actors ought not play live action characters of color, then they ought not play animated characters of color. But the validity of this extension depends upon the reasons behind the prohibition on blackface and its ilk. One reason why these practices are wrongful seems to be because of their resemblance to degrading and pejorative representations of people of color in the past, which leads to emotional harm in many who see the resemblance. We ought to avoid causing this kind of harm if there is no good moral reason to cause it; and in this case, there does not seem to be such a reason. If many are similarly harmed by the perceived resemblance between white actors voicing non-white animated characters and degrading and pejorative representations of people of color in the past, then this would be a reason to follow the Exclusive Principle. It would also explain objections to the television show in which actors of color are well-represented but the sole character of color is voiced by a white actor. There may very well be degrading or pejorative representations of people of color that the voicing of a character of color by a white actor resembles. Thus, I leave this argument open for consideration.

However, one might worry that this argument is in danger of proving too much. For instance, if no physical impersonation of a character of color by a white actor is permissible — either via the actor’s whole body or her voice alone — then it might be argued that it is impermissible for white screenwriters or novelists to write non-white characters. But following that principle may very well lead to perverse consequences, in that it might reduce the overall number of characters of color in novels, books, and TV shows. One way to block the slippery slope is to argue that impersonations of characters of color are impermissible only if they are either pejorative and degrading in themselves, or resemble some historical representation that is pejorative and degrading. It might then be argued that some impersonations of persons of color by white writers do not satisfy this condition. But if this is true, then it becomes harder to see why all vocal impersonations of persons of color by white actors satisfy this condition. And if not all of them do, then this line of argument does not strongly support the Exclusive Principle.

In her statement, Bell wrote that “[c]asting a mixed race character with a white actress undermines the specificity of the mixed race and Black American experience.” One way to interpret this claim is that white actors are unable to impersonate people of color well, precisely because they lack the requisite experience. This is an aesthetic argument; it concerns not the morality of voicing a character of color, but its goodness as art. And this might be the right way of thinking about the Exclusive Principle — not as a moral principle, but as an aesthetic one. Of course, there will probably be significant disagreement about this aesthetic claim, and I am not in a particularly good position to judge such matters. However, one wonders why a 21st-century actor could effectively give voice to, say, a 19th-century person, but not a modern-day character of color, particularly if the latter’s lines are written by a person of color. Furthermore, the political implications of the claim that even white people who are trained to use their imaginations to inhabit the mental space of people very different from themselves cannot empathize with people of color enough to impersonate them well also seem unduly pessimistic.

Society seems to be undergoing rapid change in its moral attitudes surrounding race. Many of these changes are unequivocally for the good. Even so, it is worth pausing to reflect on what exactly we wish to accomplish with these changes. As we have seen, with respect to the Exclusive Principle the key questions are whether it is the best policy to further the worthy end of promoting people of color in the entertainment industry, whether there are reasons beyond underrepresentation that are motivating its adoption, and if so, whether those reasons are ultimately valid.