Undoing White Privilege

By now we have all seen the video of African-American man George Floyd ‘s murder under the knee of a white police officer several weeks ago on an ordinary evening in a Minneapolis street that caused huge protests across the US and worldwide. Even in a culture that normalizes violence against Black bodies, this footage is particularly shocking.

Derek Chauvin has George Floyd pinned to the ground and is kneeling on his neck. Three other officers are standing, mostly off camera, hovering in mute complicity, unwilling or unable to stop what is slowly taking place before them.

The slowness is shocking. For eight excruciating minutes Chauvin kneels on George Floyd’s neck as he struggles. George Floyd calls out for his mother, begs for his life, fights for breath, gasps “I can’t breathe.” A stream of urine flows from under the car. Chauvin slowly and unflinchingly crushes the life from the man beneath his knee.

That Chauvin does not flinch is shocking. The violence is not reactive. Chauvin isn’t in a hurry, he isn’t in a frenzy, and his facial expression suggests he knows what he is about. As he slowly crushes George Floyd’s neck, he looks into the camera.

That Chauvin looks so long into the camera is shocking. The person holding the cell phone is very close to where Chauvin has Floyd’s face pressed into the road, and Chauvin looks defiantly into the camera with no hint of shame or self-consciousness. He does not care that he is being recorded. His expression seems to dare the onlooker to film him as other bystanders can be heard in the background shouting.

What can we read from the expression on Chauvin’s face? That image has been stilled and reproduced in countless media articles. It isn’t necessarily clarified in captions that this picture is taken at the moment he is murdering George Floyd – which is something that, looking at the picture, you can’t possibly tell. As he kneels on George Floyd’s neck for eight minutes Derek Chauvin looks banally into the camera. He has his hand in his pocket.

That Chauvin has his hand in his pocket is shocking. The body language of casual dismissal becomes a most vicious form of contempt – Chauvin’s face shows no rage. His expression and his gesture, as he kneels for eight minutes on George Floyd’s neck looking into the camera with his hand in his pocket, look like boredom.

Hannah Arendt coined the phrase “the banality of evil.” The phrase refers to the trial of Nazi war criminal Adolf Eichmann, and describes his part in, and muted response to, the bureaucratic systems that required him to process Jews for transportation to the death camps during WWII and enabled him to do so without troubling his conscience.

The phrase seems nevertheless apt, because of the expression and gesture of banality Chauvin personifies; his conscience is not troubled, and his expression betrays his expectation of impunity.

In a recent PBS News special, filmmaker and activist Ava DuVernay, for whom viewing videos of police violence is routinely part of her research, reflects upon what it is about this video in particular that was, as she said, ‘bringing her to her knees’: “… I could see that white officer’s face, I could see his disdain, I could see his intention (in my view), I could see the callous disregard for human life.”

The video of Floyd’s death sparked worldwide protests and support for Black Lives Matter because it was yet another instance, another instance too many for communities at breaking point, in the long litany of racist police brutality. But also because the film itself is so powerful – so close up, so intimate, and so emblematic of the system of white supremacy that routinely and indifferently crushes Black lives.

The video of Floyd’s death exposes a truth that it is impossible to look away from, a truth already known by many and which others are coming to, finally, for the first time: that white supremacy still reigns. And in this video, it looks directly at us all.

Darren Walker, President of the Ford Foundation, told PBS that: “White America was deeply wounded and shocked by the visual of [George Floyd’s] murder over eight and a half minutes; and for White America deniability of racism in our policing, and in our nation, is no longer an option.”

Whether you already knew, or whether you are coming for the first time to this knowledge, you are witness to the sickening legacy of colonialism, slavery, and racial segregation still playing out in a world which has not reckoned with the sins and the atrocities of its past.

We may be justified in our hope that the time has arrived for that reckoning, and that it will lead to real action on racial justice. But what will real action look like?

As many have been saying, reform is not enough. In the view of author and activist Roxanne Gay it is unlikely that reform could come from inside the system – the police force cannot reform itself because the institution is corrupt: “we’re going to have to really expand our imaginations to reimagine what law enforcement might look like if racism did not underpin it.”

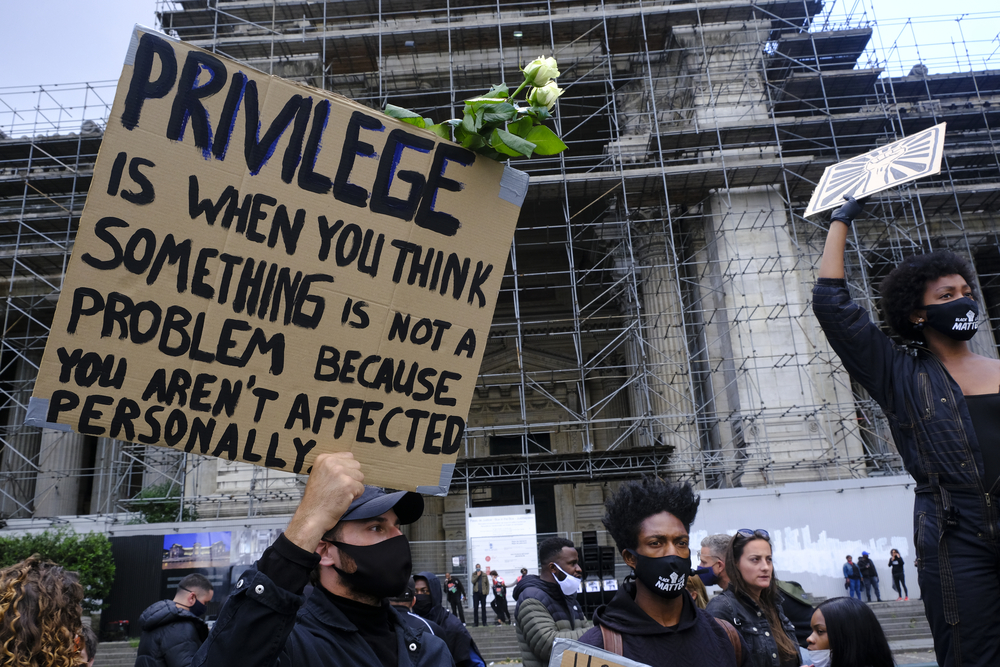

As Gay implies the system in which racism is inbuilt and white privilege is invisible cannot be reformed. Real, meaningful change will require the dismantling of white supremacy and white privilege.

The Black community, in the US and elsewhere, has a long and proud history of activism in the fight against racism for civil rights and justice, but it should not be up to Black activists, protestors, and communities to do this work. Allies in the white community are crucial for Black Lives Matter in the US, Australia, and elsewhere; but for such allies, walking with and in support of the Black community is not enough. White people need to dismantle the system of white supremacy and privilege, and find a way to decolonize our thinking and our institutions.

White support for Black resistance to racial injustice is often transient – because it can be, because white supporters can choose to be active or not on race issues, and the luxury of that choice is one expression of privilege. White support can also, in the experience of generations of Black activists, manifest as a burden. This is something white allies need to be aware of. When well-intentioned would-be allies go to Black communities and ask, “what can I do?” they are inadvertently placing the burden on Black communities to educate them. This has been a persistent problem for Black activists.

Ava DuVernay said to PBS, of people asking what to do, “my answer is educate yourself – there have been white allies throughout the history of America who have gotten together and come up with muscular strategies for change…’what do I do?’ is really asking for Black labor in this moment to help you think through what to do: trust me, there is something to do where you are.”

Being or becoming an ally in the struggle for racial justice is not about just walking into this space and asking “what can I do?” because this shifts the onus back onto the Black community. DuVernay says: “I invite Caucasian people to devise tactics and strategies – things only white people can do… strategies to dismantle these things [manifestations of institutional racism] actively.” That, she says, “would be a game-changer.”

It is incumbent on white people to know history, to understand the nature of racism and to find ways, big and small, to dismantle the system of white supremacy. We must educate ourselves, and we must undertake the work of learning to identify privilege and learning ways to refuse, counter, deflect, and subvert it.