On August 12, 2022, a twenty-four-year-old man nearly murdered Salman Rushdie for something he wrote before the man was born. The assailant set upon Rushdie as he was about to deliver a public lecture at the Chautauqua Institute in New York, stabbing him multiple times in the neck, stomach, eye, and chest and inflicting over twenty wounds. That night, Salman’s life seemed to be hanging in the balance. But the next day, the world learned that he would survive, albeit with grave and permanent injuries, including the loss of sight in one eye and use of one hand. Nevertheless, Ayatollah Khomeini’s religious decree or fatwa, issued in 1989 and calling for Rushdie’s assassination, remains unfulfilled.

Yet reading about recent statements and actions of students and administrators at Hamline University in St. Paul, Minnesota, one could be forgiven for concluding that Khomeini’s message has, at least in part, carried the day.

Last fall, an adjunct professor there was fired for displaying a fourteenth-century painting of the Prophet Muhammed in her class after a student complained that showing the image was an act of “disrespect.” In the fatwa against Rushdie, Khomeini explained that Rushdie’s murder was warranted because his novel, The Satanic Verses, “insult[s] the sacred beliefs of Muslims . . . .” Of course, no one at Hamline was calling for the lecturer’s blood. But that showing the image was, as school officials averred, “undeniably inconsiderate, disrespectful, and Islamophobic,” or that avoiding “disrespecting and offending” Islam should always “supersede academic freedom,” are ideas that seem more at home in an Islamic theocracy than a liberal democracy.

Not being an expert in the history or theology of Islamic iconoclasm, I will not engage with the argument that showing an image of the Prophet is always and clearly Islamophobic. It’s worth noting, though, that the image was created for an illustrated world history commissioned by a Muslim ruler of Persia and written by a Muslim convert. That fact in itself suggests a further fact that, at least outside of Hamline’s Office of Inclusive Excellence, is widely acknowledged: there is a broad range of views within Islam about the propriety of such depictions. As Amna Khalid trenchantly observes, it is the assumption that the Muslim community is a monolith with respect to this issue that seems Islamophobic.

But besides bolstering the argument that showing the image served a legitimate pedagogical purpose and was not aimed at causing offense, the contention that the image is not insulting to all Muslim is somewhat beside the point. The real question is: even if it were, would that automatically make showing it in a university classroom impermissible?

Suppose that, in a class about the history of European political satire or journalistic ethics, a professor displayed the cartoons whose publication by the French satirical magazine Charlie Hebdo led to the murder of twelve people in 2015. These cartoons are undeniably irreverent and, yes, even insulting and offensive to some. But unless showing them has no pedagogical benefit under any set of circumstances — unless it is undeniably an attempt simply to insult students — academic freedom absolutely supersedes these students’ hurt feelings. The very idea of an institution dedicated to the production and dissemination of knowledge, through the exchange of ideas and arguments among diverse participants, each with their own unique perspective, depends upon this principle. If anyone’s bare claim to be disrespected, offended, or insulted is sufficient to justify censorship, then there is almost no topic of any human interest that can be discussed with the candor required to examine it at any level of depth or sophistication.

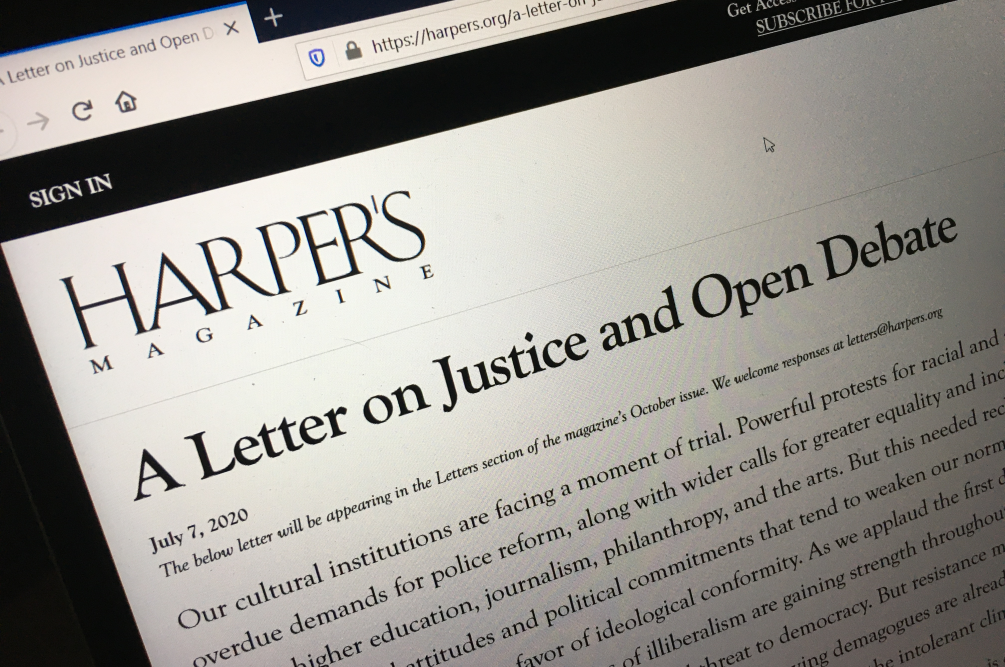

It seems, however, that a non-trivial number of students at Hamline disagree with me. When the university’s student newspaper, The Oracle, published a defense of the lecturer written by Prof. Mark Berkson, the chair of the Hamline Department of Religion, the ensuing backlash led its editorial board to retract the article within days. In an unsigned editorial explaining the move, the board wrote that because one of its “core tenets” is to “minimize harm,” the publication “will not participate in conversations where a person must defend their lived experience or trauma as topics of discussion or debate.” In other words, publishing the chair’s defense adversely affected other students by “challenging” their “trauma.”

There are two features of this argument I find interesting: the “minimize harm” principle, and the use of the term “trauma.” Both, I think, can be fruitfully examined in light of a useful distinction the philosopher Sally Haslanger draws between a term’s manifest concept and its operative concept.

According to Haslanger, a term’s manifest concept is determined by the meaning that language users understand a term to have; it is the term’s “ordinary” or “dictionary” definition. By contrast, its operative concept is determined by the properties or entities actually tracked by the linguistic practice in which the term is employed. In her work on race, Haslanger observes that the manifest concepts associated with the term “race” and similar terms include some biological or physical components, yet the way we actually apply these terms does not track any physical characteristic (think of how the term “white” was once not applied to Sicilians).

Using this distinction, we can see how the editorial board performs a neat sleight of hand in its use of the term “trauma.” The dictionary definition or manifest concept of “trauma” is something like Merriam-Webster’s “a disordered psychic or behavioral state resulting from severe emotional stress or physical injury.” When The Oracle’s editorial board uses the term, and further, implicitly asserts that no one should question whether a person’s trauma is warranted or justified, this sounds eminently reasonable because of the term’s manifest concept. But when we look at how the board actually uses the term, it becomes clear that its operative concept is something like “insult, offense, or a feeling of being disrespected.” Once we see this, the claim that a person’s “trauma” should never be questioned begins to look quite doubtful. A person may be mistaken in feeling insulted or offended, and in such situations, it may sometimes be permissible to respectfully point this fact out to them. This is precisely what Prof. Berkson was trying to do in his defense of the lecturer. And once again, I must insist that it is even sometimes justifiable to cause offense in the classroom in order to achieve a legitimate pedagogical goal.

There is another sleight of hand at play in the board’s “minimize harm” principle. The board invokes the Pulitzer Center’s characterization of this principle as involving “compassion and sensitivity for those who may be adversely affected by news coverage.” On its face, this seems beyond reproach — particularly since the Center’s definition clearly implies that newspapers may justifiably publish material that adversely affects others, so long as they do so in a sensitive and compassionate manner. But the board’s application of the principle to this case reveals that for it, “minimize harm” really means “cause no harm,” or even “cause no offense.”

While the principle of minimizing harm implicitly calls for exercising moral judgment in weighing whether the harm caused is justified by the benefits to be gained, and moral courage in defending that judgment when it is challenged, the principle of causing no harm is, for journalists, equivalent to a demand that they not do their job.

For example, if The Oracle published an article uncovering massive corruption in the Office of Inclusive Excellence that led to multiple school officials’ termination, it would cause concrete harm to those officials. “Cause no offense” is, of course, an even more craven abdication of the journalist’s vocation.

There is a final point that I think is worth making about this sorry affair. Before showing the painting to her students, the lecturer reportedly took every possible precaution to safeguard their exceedingly fragile mental health. She made that particular class activity optional. She provided a trigger warning. And she explained exactly why she was showing the painting: to illustrate how different religions have depicted the divine and how standards for such depictions change over time. She behaved like a true pedagogue. None of this prevented the mindless frenzy that followed. This suggests that instead of actually helping students cope with “trauma,” trigger warnings and the like may actually prime students to have strong emotional reactions that they would not otherwise have. Indeed, the complainant told The New York Times that the lecturer’s provision of a trigger warning actually proved that she shouldn’t have shown the image. What a world.