This piece begins a Considered Position series that reflects on the United States’ claim to being a “flawed democracy.” (Part II, Part III, Part IV)

Introduction

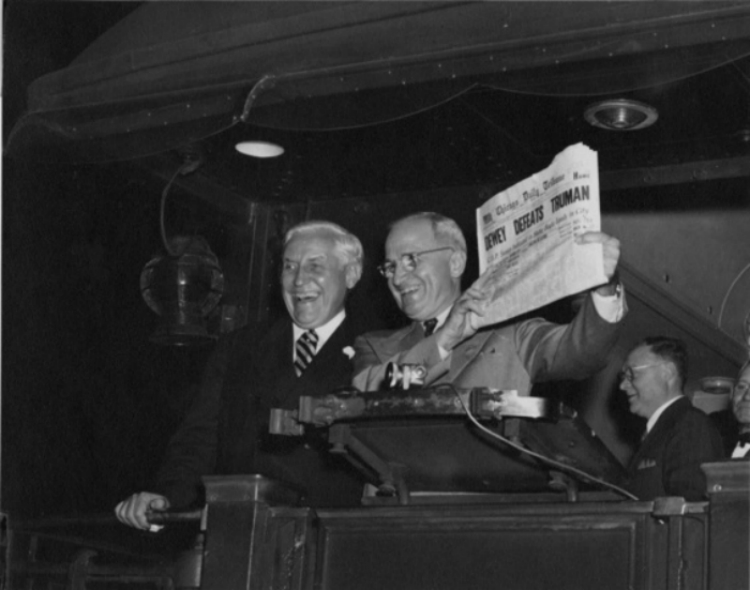

2020 is an election year. As a nation, we will talk a lot about the candidates, who they are, what they stand for, and what they plan to do. But how much does that all matter if the elections themselves are broken?

As Americans we pride ourselves on our commitment to democracy. While most nations were still under monarchs, we alone managed to permanently throw off the monarchical yoke. But how democratic are we really? As this series will discuss, our government has earned its designation as a “flawed democracy.”

We will consider numerous problems of enfranchisement, minority rights, and voter participation. We will also consider how all these problems have not necessarily come from malice or stupidity. Unfortunately, it is very easy for many people, all individually rational and good-hearted, to exact great harm on our society and government.

Unlike most writing on politics, this series will not seek primarily to put blame on any group or groups. Rather, we will try to understand the systems that have incentivized people to act in ways contrary to the general interest. As much as we as Americans like to think of ourselves as free, no one is free from the influences society has on us from birth till death in all our actions.

Frequently we will consider these systems and problems through a moral lens. Most political problems and disagreements have their roots in moral disagreements. And, the Prindle Institute for Ethics holds that the only way to become better at resolving moral disagreements is to develop the skills of moral reasoning. Moral reasoning is the practice of considering a moral problem from different perspectives, weighing the different moral factors at stake, and coming to an understanding of the right action or actions to take.

You might want to put on some cheerful music as this discussion of the numerous systemic problems with our electoral system is almost certain to prompt feelings of sadness and hopelessness. Got it playing? Well then, strap in as we first take a look at one of the most obvious problems with our democracy: the fact that millions of US citizens have, like American Revolutionaries once did, no representation in the governing bodies whose laws they must obey.

Disenfranchisement

If you’re a citizen, if you were born in this country, if you are mentally sound, and if you have committed no crimes, then you likely have the right to vote for the president and members of Congress as soon as you turn 18. But it is only likely. It is not guaranteed. In fact, about 4 million Americans who fit all these criteria cannot vote. That’s more people than who live in the five least populous states. So why can these people not vote? Well, they don’t live in US states. Most of them live in US territories and the remaining 700,000 reside in our nation’s capital. Let us consider both of these groups in turn.

Island Territories

Most people know about Puerto Rico. It is part of the US and yet not a state, even though it has more people (3.7 million) than 20 US states. But many do not know that an additional 300,000 people live in Guam, the US Virgin Islands, the Northern Mariana Islands, and American Samoa. American Samoans aren’t even considered citizens, only “American nationals,” though there is a court case pending challenging this classification. The reason these citizens have been denied voting rights goes back to a series of Supreme Court cases and decisions collectively referred to as the “Insular cases.”

These cases, decided in 1901, were rooted in racism and colonialism. The Court ruled that the US could possess these territories without granting their residents full constitutional rights. According to them, “those possessions are inhabited by alien races, differing from us in religion, customs, laws, methods of taxation, and modes of thought,” and so “the administration of government and justice according to Anglo-Saxon principles may for a time be impossible.” The designation of American Samoans as “nationals” rather than “citizens” reflects the colonial mindset. European nations often used this designation for their own colonial subjects.

Given that colonialism often has the purpose of creating military advantage and extracting economic resources for the colonizers, it makes sense why the US would not want the colonized people to have a vote. But, of course, nowadays that line of reasoning will not convince many people. We recognized now that these people are people. So why, in our “democratic” nations does this demos, Greek for “people,” not get to vote?

It comes down to a matter of constitutional law. According to the Constitution, Senators and House Representatives must be elected by the people of the States. Each state gets 2 Senators and a number of Representatives based on its population. Statehood here is critical. Any of the territories could become a state. However, statehood requires the same approval as do laws when they are passed. Both Houses and the president must agree. This will be difficult to accomplish for any territory that wishes to become a state and it always has been. Some of the most divisive politics of our nation’s history surrounded the admission of various states during the antebellum period. Few slave-holding states would be willing to vote in favor of admitting a free state and vice versa. Thus, the democratic rights of these citizens are dependent on two parties agreeing which, in recent times, agree on little.

It’s a hard sell for Republicans and for good reason: suppose you had power to make change for (what you believed to be) the better. Would you be willing to give up that potential for good just to give the right to vote to some people you know will vote (in what you believe to be) the wrong way? Denying the democratic rights of others, then, is not necessarily irrational and requires no malice towards those you disenfranchise. If you have confidence in your beliefs (which you must to hold them at all), then it makes little sense to give decision-making power to those who hold beliefs opposite yours. The issue comes down to deciding whether to preference your specific political beliefs or your broader political beliefs about the righteousness of a democratic system of government.

And there are some other legitimate worries too. First among these is a worry stemming from democratic values: Puerto Rico and other territories should only be made states if their peoples want to become states and it’s not clear that they do. Puerto Rico has regularly had referenda on statehood but no referendum has ever shown definitive public support for statehood. The latest referendum showed 97 percent of Puerto Ricans supporting statehood. However, there was only 23 percent turnout after the anti-statehood Popular Democratic Party urged people to boycott the vote. Former Governor of Puerto Rico Aníbal Acevedo Vilá, a member of this party, sees a number of economic and cultural problems with gaining statehood.

Another referendum is on the 2020 ballot. So we will soon see if the people of Puerto really agree with Vilá. If Puerto Ricans do not support statehood, it is hard to argue that they should be made one. The stance many politicians take, including current Democratic Presidential nominee Joe Biden, is neither that Puerto Rico should be a state nor that it shouldn’t, but that the people of Puerto Rico should decide for themselves.

There are probably a few Americans who want to keep the historical colonial relationship we have with Puerto Rico and the other island territories, but it’s not clear that this is the reasoning driving most of those who oppose Puerto Rican statehood. On the far opposite side to those who would treat Puerto Rico as a colony are those who advocate its self-determination. The UN Special Committee on Decolonization has long demanded that Puerto Rico be allowed to be either a state or an independent nation. Most colonies, historically, have pursued independence rather than integration with the colonizing state. In fact, in 1914, Puerto Rico’s own elected Congress voted overwhelmingly for independence and was subsequently ignored.

The District of Columbia

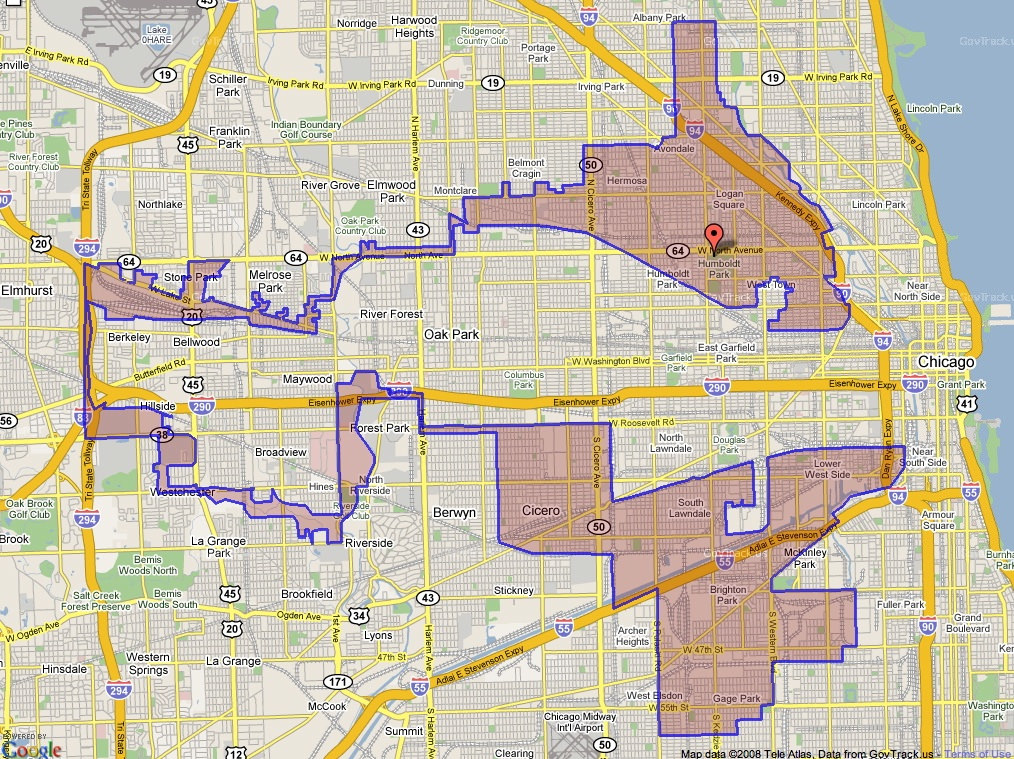

So maybe the island territories shouldn’t have the vote. Perhaps they don’t want it. But what about somewhere that does? The District of Columbia is our nation’s capital, but it’s also a city of more than 700,000 people, none of whom have Congressional representation. In fact, while they can vote for President, they can only do so because of an amendment to the Constitution passed in 1961. And though this amendment gives them the right to vote, their votes only count as much as the least populous state, giving them 3 electoral votes, the same number as Alaska, a state with one third the population of DC.

Why didn’t the Founders give them this right in the original Constitution? Well, no one was meant to live there besides some members of the government and some support staff. Furthermore, the Founders worried that having the nation’s capital in a state would allow that state undue influence over the federal government. As James Madison wrote in the Federalist 43, they worried about “a dependence of the members of the general government on the State comprehending the seat of the government” and the possibility of a state bringing “on the national councils an imputation of awe or influence.”

Even so, neither Madison nor any other of the Founders could have predicted the incredible population growth that was to come in the next two centuries. So perhaps their attitudes would have softened. Indeed, one of the slogans of the American Revolution was “taxation without representation” and this same slogan now adorns all the license plates of DC residents. DC residents pay more federal income tax per person than any other state and yet have no representation in Congress. This injustice is compounded by the fact that Congress has total dominion over DC. As part of a federal system, states have powers that Congress and the federal government cannot override. DC has no such power of self-determination. Though they can pass laws and ordinances, they can all be vetoed by Congress.

DC is an interesting case because proponents on both sides, of statehood and of the status quo, claim to be upholding basic principles of democracy. On the one hand, those who support statehood want the most basic form of democracy for DC, the right to vote and the right to self-determination. On the other hand, those who oppose it believe in the concept of “one man, one vote.” They don’t want citizens of DC to have more than their share of power over the federal government. Proponents of statehood see the issue as a dichotomy between giving DC citizens equal rights and leaving them with no rights. Opponents see it differently: either DC has no political power or they have more than other citizens for an arbitrary reason, their geographic location. Seen that way, statehood becomes a much more tangled issue.

However, not all opponents of giving DC’s citizens political rights have such defensible positions. First of all, like Puerto Rico, DC would be likely to bring more Democratic Senators and Representatives to Congress since they vote overwhelmingly for the Democratic Party in presidential elections. In fact, this was the reason Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell gave for refusing to consider DC statehood, likening the increase in the number of Democratic Senators incoherently to “full-bore socialism.”

And, again like Puerto Rico, some opposition to DC’s citizens having political rights stems from racism; Black people represent the majority of DC’s population. In fact, a number of the arguments Republican Congressmen presented in the House to oppose DC statehood did not concern the worry of Madison about state influence on the federal government at all. Rather, Republican Congressmen mostly made arguments about the largely Black city being unable to govern itself. They referenced the city’s crime rates, public school quality, and governmental corruption. These might be valid concerns if any other state with the same issues were similarly threatened with disenfranchisement. But, of course, they are not. And in any case, the question remains why any of those factors ought to affect people’s fundamental right to representation in government.

The genuineness of these concerns is also cast into doubt by the fact that they fit into a pattern of racially motivated reasoning used to support the disenfranchisement of DC’s residents. During Reconstruction, John Tyler Morgan, a former Confederate soldier and then US Senator argued that Congress had “to burn down the barn to get rid of the rats…the rats being the negro population and the barn being the government of the District of Columbia.” The legislation he supported — removing power that had been given to the city — was soon passed.

Even if racism does play a part in motivating opponents of DC’s statehood, they may still be right. People can argue the right things for the wrong reasons. Australia for one is also a federated state and also has its capital in a distinct territory, the Australian Capital Territory (ACT), that does not have the same full rights of self-determination as do the other states. We are not a lone oddity in not wanting the people immediately around the capital to have undue power over the federal government. Unlike the US, however, the people of the ACT do have representation in their legislature. At the same time, that representation is very limited and is not proportional to the population. They have more people but fewer representatives than the state of Tasmania. This situation is similar to DC’s limited power in the Electoral College like I mentioned before.

The opposition surrounding DC’s statehood is a tangled mess of racist rhetoric and legitimate concerns that come with a federal style of government. Its supporters and opponents both base their arguments in democratic language. The same goes for Puerto Rico and the other island territories where everyone agrees that what the people say goes, only they disagree on what the people say. Therefore, excepting the racism that underpins some arguments against enfranchisement in both of these areas (and there is a lot of this), the debate is not between those who support democracy and those who don’t. Rather, it is between people with different interpretations of democracy.

Continue to Part II