Bloomberg: Biasing Elections With Billions

There are few things as closely connected as money and politics. In the 2016 election alone, $6.5 billion was spent. Of that, $2.4 billion went toward the presidential race and $4.1 billion went toward Congressional races. In the 2010 election, about half of the money spent on Congressional races was from large donations (more than $200) by individuals and about a quarter came from organizations known as PACs. About ten percent came from candidates self-funding. There is a sort of nobility to a candidate funding his own campaign. Most candidates accept money from organizations, companies, and rather well-off individuals and end up feeling an obligation to act in their interests. But those funding their own campaigns, in contrast, are beholden only to the people who they receive votes from.

Nonetheless, few candidates are able to fund their own campaigns. While a reasonably well-off individual might be able to completely self-fund a campaign for Congressional office in a small district, virtually no one can afford to run for President without accepting money from other people and groups. In 2016, both Donald Trump and Hillary Clinton spent around a billion dollars. Little of that was their own money. This is a little surprising when it comes to Trump, who is himself a billionaire. That even Trump did not finance his own campaign shows the difficulty of doing so. However, in the 2020 election, one candidate is trying to do just that.

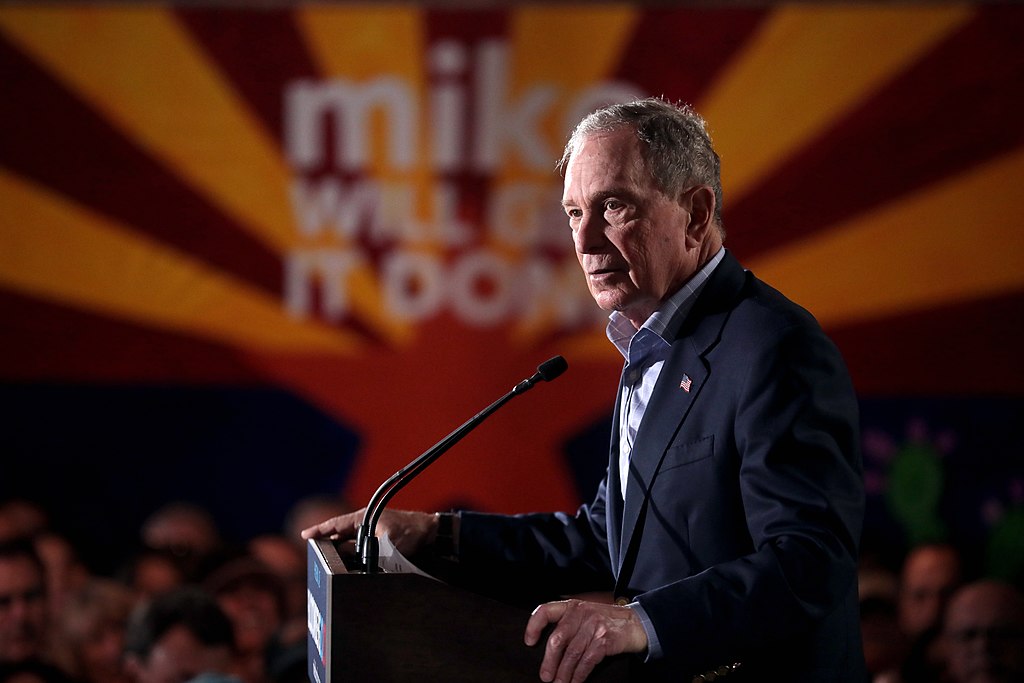

Michael Bloomberg has spent $450 million of his own money trying to win the Democratic Primary, so far. That is more than all the other candidates combined. And yet, few have lauded Bloomberg for the nobility of being unbeholden to special interests, financing his own campaign for the Democratic nomination. Bloomberg’s top campaign adviser, Howard Wolfson, has promoted this very idea, saying that Bloomberg “cannot be bought” and that he is “wholly independent of special interests.” Even so, Bloomberg has been criticized for attempting to “buy his way to being president.”

There are a few moral objections that people might raise to the Bloomberg campaign that might outweigh the value of the independence of his self-funding. These can be more clearly explained by consideration of why it might be good for a candidate to fund his own campaign. A candidate who funds his own campaign for noble reasons, who wishes to avoid being bound by special interests, typically accomplishes this feat through great personal sacrifice. Most Americans make much less over the course of many years than the cost of a single election. So for the few who do self-fund, it often represents an enormous financial burden. But, Bloomberg has a net worth of over $60 billion. The money he has spent so far represents only 0.7 percent of his net worth. The median American has a net worth of $97,300. For him, an amount comparable to Bloomberg’s spending on the election would be around $700. Thus, this is no great sacrifice for Bloomberg.

Another objection to Bloomberg’s campaign has to do with the self-funding candidate’s desire to avoid ties to special interests. We typically define a special interest as “a person, group, or organization that tries to influence government decisions to benefit itself.” These may be large lobbying groups for, say, tobacco or oil companies. Or, they may be extraordinarily wealthy individuals who wish to advance the interests of their companies, or to limit their taxes. The problem with Bloomberg may be that he is, himself, a special interest. Or perhaps, as Jim Newell argues, the issue with Bloomberg’s campaign is not its avoidance of special interests, but of “indifference to ‘interests’ altogether.” The practice of politics in a democracy assumes as axiomatic the idea that change cannot be accomplished on one’s own. Only through working together, compromising, and acting in accordance with the harmonized interest of a great deal of citizens can elections be won and change be wrought. Bloomberg’s campaign is an affront to this idea of democratic politics and is thus objectionable on those grounds.

But, what does this matter anyhow? In some sense, it is absurd to say that Bloomberg, or anyone, could “buy” an election. Unless the election process is wholly corrupted, elections are won in democracies by votes. Those votes can be affected by campaigns and advertisements for candidates, but an unlikable candidate whose political positions are antithetical to the majority of voters’ values cannot win at the ballot box, regardless of the amount of money they spend. People are not mindless drones whose votes are determined by dollar amount of campaign spending: Hillary Clinton spent nearly fifty percent more on the 2016 election than Trump and still lost. Furthermore, voters have a number of other ways to learn about candidates besides advertisement. And, in Bloomberg’s case, these have proven harmful.

At the debate just prior to the Nevada Democratic caucuses, all the other candidates thrashed Bloomberg for minutes on end. While there is no objective measure of victory in a debate like this, The Washington Post placed Bloomberg under the “loser” category, particularly for coming off as “technocratic,” a word that signifies that Bloomberg seemed out-of-touch or elitist. If The Washington Post is right, it does not matter how much Bloomberg spends: if the people don’t like him, they won’t vote for him. And, if they do, they should vote for him, regardless of the money he spent, since citizens of a democracy are assumed to vote for the candidates they think are best (though this doesn’t always play out).

Bloomberg has the right to free speech, to advocate for himself, and to encourage others to vote for him. As the Supreme Court has consistently ruled, campaign spending is protected speech up until it is, or implies, corruption. Essentially, the debate comes down to how one believes candidates, and ultimately those in power, should be selected. Citizens of a democracy should obviously vote for who they think is best. But, that judgment of “who is best” is complicated by the various factors that go into it. Ideally, voters would make their decisions with perfect knowledge of the candidates’ positions and characters. In reality, only a small amount of the relevant information makes it to most voters. And, when that is the case, it matters who has the largest loudspeaker to communicate. Money matters because it allows candidates to reach voters more effectively. In some cases, this means money can decide elections, not because citizens are unable to decide for themselves which candidate is best given what they know, but because political advertising can affect what it is they know in the first place. Particularly if the political advertising is deceptive as to the positions and character of a candidate, or as to the positions and characters of their opponents, voters will be making bad decisions. They will make rational decisions, but not well-justified ones. Since lying in political advertisements is legal, this is a grievous concern.

When June rolls around, we will know if Bloomberg’s self-funded campaign was ultimately successful. Voters will decide, even if their decisions are not based on facts. An ABC News/Washington Post poll from February 14-17 shows Bloomberg being most popular among 15 percent of the national population, second only to Bernie Sanders, a man known for decrying the billionaire class, and equal to former Vice President Joe Biden, thought only months ago to be a shoo-in for the Democratic nomination. Whether Bloomberg wins or not, it is safe to say his actions will shape the status quo for the future, showing other billionaires that it is possible to participate in elections in a significant way, just by spending huge amounts of money.