Should Political Apparel be Allowed in Polling Places?

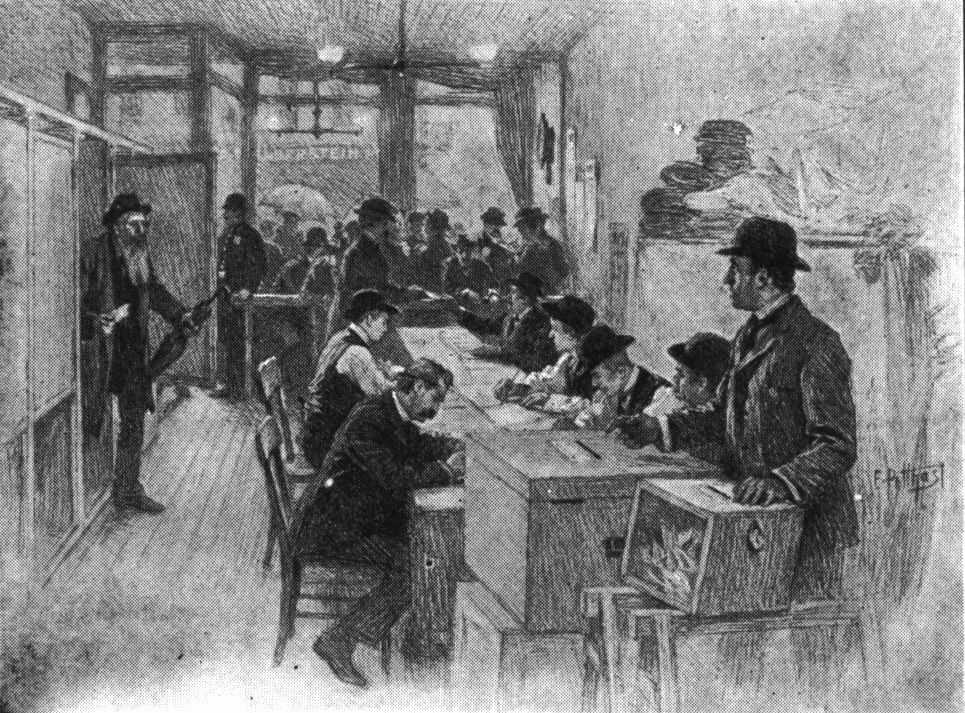

Showing up to cast a vote in an election in the United States in the 18th and 19th centuries was a very different experience from the one with which we are familiar today. The occasion of casting a vote was a celebratory one, often attended by much food and drink. Voting was also a public act. In some cases, it was a matter of providing a signature under a candidate’s name, or vocally calling out one’s support for a particular candidate. Voter intimidation, often involving acts of violence, was common. Even when votes were cast on paper ballots, the standard was that a voting process was fair when “a man of ordinary courage” could make it to the voting window. The rowdy and dangerous atmosphere involved in casting a vote was offered as a weighty reason that the right to vote should be denied to women. In fact, the practice of voting was so corrupt, that one theory explaining the mysterious death of Edgar Allen Poe was that he was the victim of “cooping”—the practice of kidnapping less fortunate (often homeless) members of society, getting them drunk, and forcing them to vote repeatedly for a particular candidate.

In the 21st century, voting, at least in many respects, is viewed as a more solemn act. The Supreme Court has consistently maintained that a polling place should be a forum in which people can peacefully reflect on the decisions they’ll make while engaging in one of their most important civic duties. Obviously, the knife fights and public intimidation of centuries past have no place in our contemporary voting locations. But how far is too far when it comes to the government regulating what kind of behavior can take place when citizens show up to vote?

This is a question that was pressed in the courts by citizen Andrew Cilek and the Minnesota Voters Alliance. In 2012, Cilek showed up to vote wearing a Tea Party Patriots shirt emblazoned with the phrase “Don’t Tread on Me,” as well as a button that read, “Please I.D. Me.” In accordance with Minnesota law, Cilek was turned away from polling places twice before he was finally permitted to vote, and he was allowed to do so only after an election judge recorded his information for use in potential further action against him.

The law in question forbids three main practices in the vicinity of a polling place on Election Day. First, campaigning for a political candidate or ballot item is not permitted within 100 feet of a polling place. This means that no staffer or supporter of any policy or candidate on the ballot can loiter outside of a polling place trying to induce or persuade a voter to come around to their position at the last moment. Second, and relatedly, the distribution of political badges, buttons, or insignia is disallowed within close proximity of a polling place. Finally, third, the law prohibits citizens from wearing political badges, buttons, or any other political insignia inside the polling place. It is this third aspect of the law with which Cilek and The Minnesota Voters Alliance took issue. They argued that the prohibition on wearing political badges, buttons, or insignia violated the first amendment rights of citizens like Cilek. The case made it to the Supreme Court in the case of Minnesota Voter’s Alliance v. Mansky. The Court ruled in favor of The Minnesota Voter’s Alliance and ruled the Minnesota law unconstitutional on its face. This means that the law was not simply unconstitutional as it was applied to Cilek’s case, but, rather, it was unconstitutional as written, in all of its applications. On first glance, this may seem to be a victory for Cilek and the MVA, but the court did not reject the law for the reasons the Petitioners would have hoped. Instead, the Court determined that the third section of the law was overly vague. The word “political” could mean all sorts of things. To know whether a piece of apparel constituted political expression or support for a political candidate, an election judge would have to be exceptionally well versed on the issues and the in-depth platforms of every political candidate on the ballot. The Court saw this as an unreasonable expectation. The law provided no sensible way to draw a distinction between the kind of apparel that could be worn inside the polling place and the kind that could not. This is not, in principle, an insurmountable problem. The majority opinion, written by Chief Justice Roberts in this case, makes perfectly clear that states have a right to legislate speech in forums such as polling places. If the Minnesota law laid out restrictions in a more reasonable way, the law would likely be unproblematic from a constitutional perspective. This is surely not the result for which Cilek and the MVA were hoping.

There are ethical questions concerning the proper balance of values in this case and in other cases like it. Most states have laws restricting certain apparel in polling places. Are these restrictions morally justified?

States clearly have an interest in ensuring that polling places are safe and free from intimidation. Citizens should comfortable going out to vote without fear of threats or violence. They should feel that they could vote in the way that their consciences dictate without any pressure from anyone else. If we want our government to truly be chosen by the people, votes should be cast without interference on Election Day. We’ve come a long way in this respect, and it is good that government continues to see to it that polling places are places where citizens feel comfortable.

Though states may have this legitimate interest, some argue that no citizen is interfering with that objective when they show up at a polling place wearing a t-shirt supporting their favorite candidate or preferred policy. There is no reason to think that apparel contributes to voter fraud or that it intimidates other voters in any real way. What’s more, freedom of expression through apparel choice has value. People frequently feel a sense of strength and empowerment when they can wear what they want. It’s good for citizens to feel excited about the political process. Some argue that restricting free speech rights to protect against a harm that may be non-existent is an unwarranted exercise of state power.