The media has not always had a great track record when it comes to covering scientific and academic issues. It’s often noted that the news media report findings with exaggerated or sensationalized headlines, like how coffee can help reverse liver damage or smelling farts might be healthy. Reporting on studies can be problematic for several reasons, but there may be another kind of reporting that is even worse: the “expert(s) say” article. These articles use expert testimony (supposedly based on one’s expertise in a specific field) to comment on current public policy debates. But illicit appeals to authority threaten to shatter what little public trust remains.

There is nothing inherently wrong with appealing to expert testimony, and there are a great many articles where experts communicate meaningful facts and insights to their audience. However, as anyone who has taken a critical thinking course will tell you, there are only certain circumstances where appeals to authority are justified. To be legitimate, the authority appealed to must be generally recognized as an expert and their testimony must be based on their particular expertise. The reason we accept a claim on the basis of someone’s say-so is because they represent a broader group of people following a larger process of peer review meant to fact-check research, reproduce scientific results, and hold individuals accountable for their claims.

We often rely on experts to explain issues of public importance that may not be widely understood, like how the legal process works or how a virus can spread. Expert testimony can also be a way of combating misinformation and building trust, as (ideally) an expert can point to tangible ways to demonstrate the truth of what they are saying. In general, people are more willing to trust information coming from a credentialed expert than that coming from a journalist or media personality.

Unfortunately, there are many ways in which we can abuse that public trust. Consider all the news segments and articles that turn to psychologists or “body language experts” to speculate about the mental state of a person without previously examining them. Asking an expert to weigh in with limited information confuses speculation with news. This means that claims characterized as expert testimony are sometimes nothing more than opinions. People comment on subjects beyond their field of expertise or ignore the lack of consensus within their epistemic community. This practice risks putting the stamp of legitimacy on claims that do not deserve it.

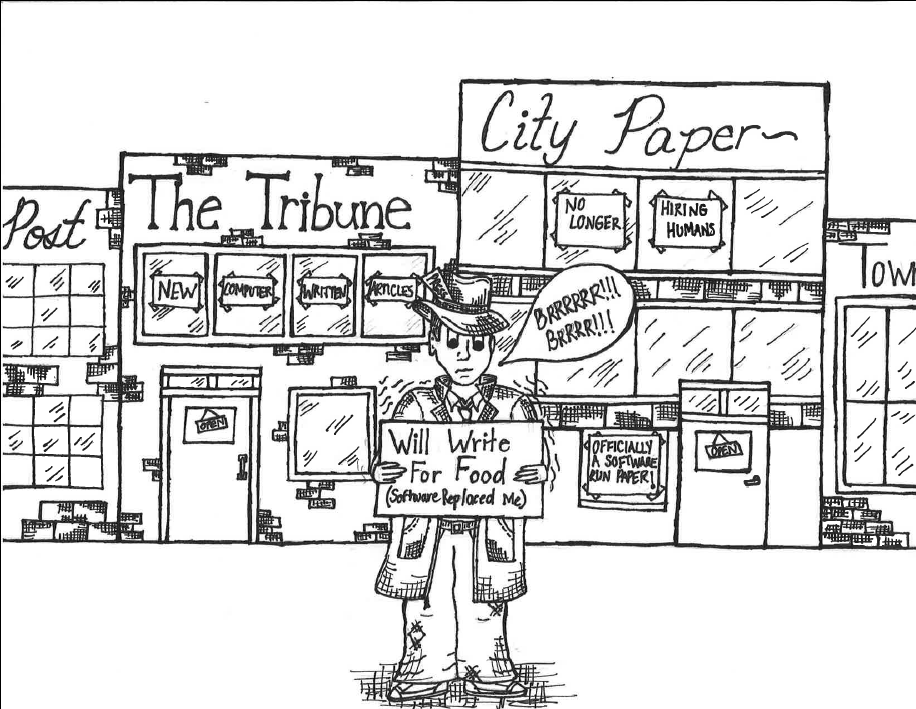

There are examples of similar “expert says” articles, some of which unnecessarily rely on experts to tell you things you already know or to simply express an opinion. Did you know that experts say that complicated passwords can save you from hacking? Did you know that experts believe that women’s apparel should have more pockets? Did you know that according to wetland experts, wetlands are too important not to protect? Or, that according to one expert, the pandemic is “far from over”? Is the public enlightened when an expert claims that a politician not taking a stance on remote work is “surprising” or that if the financially unstable Canada Post doesn’t stabilize soon it could “go the route of Blockbuster”? According to one article, experts believe AI-powered hate content is on the rise (again without a specific claim to substantiate this), while another acknowledges that there is no expert consensus on AI risks.

Recently, the Canadian government made changes to the passport, removing depictions of Canadian history. According to an “expert” – an associate professor of rhetoric, writing, and communications – the critics were engaged in “troll politics” and the entire issue was “utterly fabricated” for the culture war. Such “expert” testimony is about a controversial issue and cites nothing to substantiate the claims. While their expertise may deal with communication, it’s not immediately relevant to the cultural or historical issue. These opinions are disguised as something more legitimate than they ultimately are.

It is not difficult to find articles loaded with similarly hollow “expert” claims – where it isn’t clear what the person is an expert of or where opinions are the only thing on offer. The media can further manipulate the message by cherry-picking experts or relying on one expert’s idiosyncratic views. Ultimately, we do a disservice to the public as well as real experts by appealing to expertise in the way they do. By continuing to allow opinions to be disguised as facts, we undermine trust in genuine expertise. Not only must the media do better in vetting and presenting claims, experts too must learn to be more careful about weighing in on a controversial topic. Expert testimony shouldn’t ever simply replace the critical thinking process.