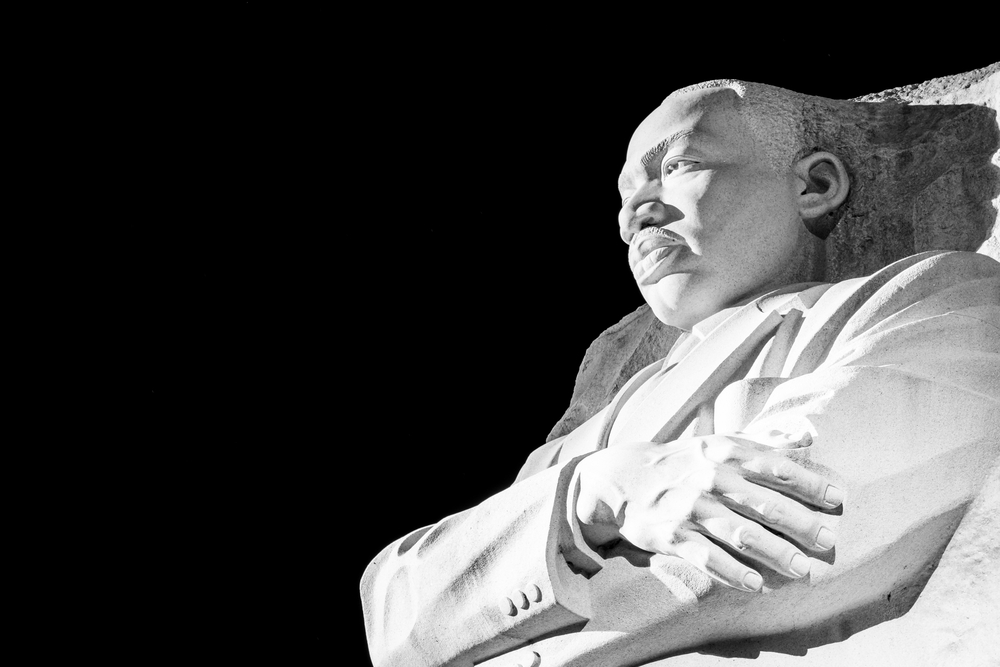

The increasing polarization of American society is perhaps most evident when it comes to issues of race and gender. In 2016, 57% of Hilary Clinton supporters said that it is a lot more difficult to be a Black person in the United States than it is to be a white person, with that number increasing to 74% of Joe Biden supporters in 2020. The number of Trump supporters, however, who thought that it was a lot more difficult to be Black, actually shrank from 11% in 2016 to 9% in 2020.

A similar dynamic has occurred with gender issues as well. Only 26% of Clinton supporters agreed that the obstacles that keep women from getting ahead are now largely gone, a figure that then decreased to just 20% of Biden supporters. For Trump supporters though, the percentage that agreed such barriers were largely gone increased from 72% in 2016 to 79% in 2020, making the issues of race and gender marked illustrations of the increasing divide between liberals and conservatives.

How has this polarization affected American society? In very polarized environments, citizens are likely to become more tribal, increasingly shutting out those of a different political persuasion. We spend more time with people who look, talk, and think like us, making the political opposition more and more unfamiliar.

This uptick in tribalism then allows citizens to become more uncharitable. By interacting less with those on the other side of the aisle, it becomes harder to empathize with their perspective and far easier to see them as either ignorant, or even downright evil.

Finally, as voters become more entrenched, they are likely to be more antidemocratic. Because the political opposition cannot be trusted, citizens are more open to leaders who seize political power in ways that undermine typical democratic processes.

None of these tendencies, of course, will help heal the sharp divide on issues of race and gender. As citizens become more tribal, uncharitable, and antidemocratic, the fault lines between camps will only become more severe.

Furthermore, when polarization occurs on issues of race and gender, the tribal boundaries are increasingly drawn along racial and gendered lines. Black and Hispanic voters remain overwhelmingly Democrat, for example, while white voters lean Republican.

And in an emerging trend, there is now a growing political divide between men and women as well. The gap between how young men and women identify politically is rapidly increasing.

One approach to improving the current political climate is by focusing on educating for the civic virtues. While talk of citizenship or civic virtue might sound quaint or old-fashioned, the civic virtues are simply the habits that citizens need to support a healthy, well-functioning political community. These virtues are especially critical for liberal democracies, as democratic nations ultimately depend on the political engagement of their citizens.

Let’s take the former challenges raised by polarization. To begin with, the civic virtue of tolerance can combat the rise in antidemocratic sentiments. A tolerant person accepts the beliefs or practices of others even if they view those beliefs and practices as objectionable. This acceptance does not require, of course, that the tolerant person takes on these beliefs and practices as their own, but only that they permit others to continue with their ways of life.

Toleration merely requires refraining from coercing and controlling others, but the civic virtue of mutual respect calls people to a deeper appreciation of their fellow citizens. Also called civic egalitarianism, mutual respect encourages citizens to acknowledge the value that others bring to the political process and view them as well-intentioned, rather than regarding them as either ignorant or evil.

Finally, the virtue of neighborliness can help us overcome our growing tribalism. Instead of giving in to permanent transience, we can get to know those around us regardless of their political persuasion. This will then help us to be more empathetic with those whom we disagree as we come to realize that they are our friends and neighbors.

Of course, even if citizens become more tolerant, respectful, and neighborly, this will not solve all of our political problems. Real issues would remain, and civic virtue will not answer some of our deepest and most abiding questions about how to live in community, but decreasing polarization would put us in a better position to tackle those challenges together.

At the same time, though, the civic virtues can do more than simply helping us overcome polarization. The virtue of justice is integral for a well-functioning society, and if we as citizens become more just, this will then help us to tackle both individual and structural injustices related to race and gender.

Civic virtue, then, can play a much larger role than just reducing polarization. Education for the civic virtues isn’t just about getting along, it’s about creating citizens that are equipped to create a flourishing society.