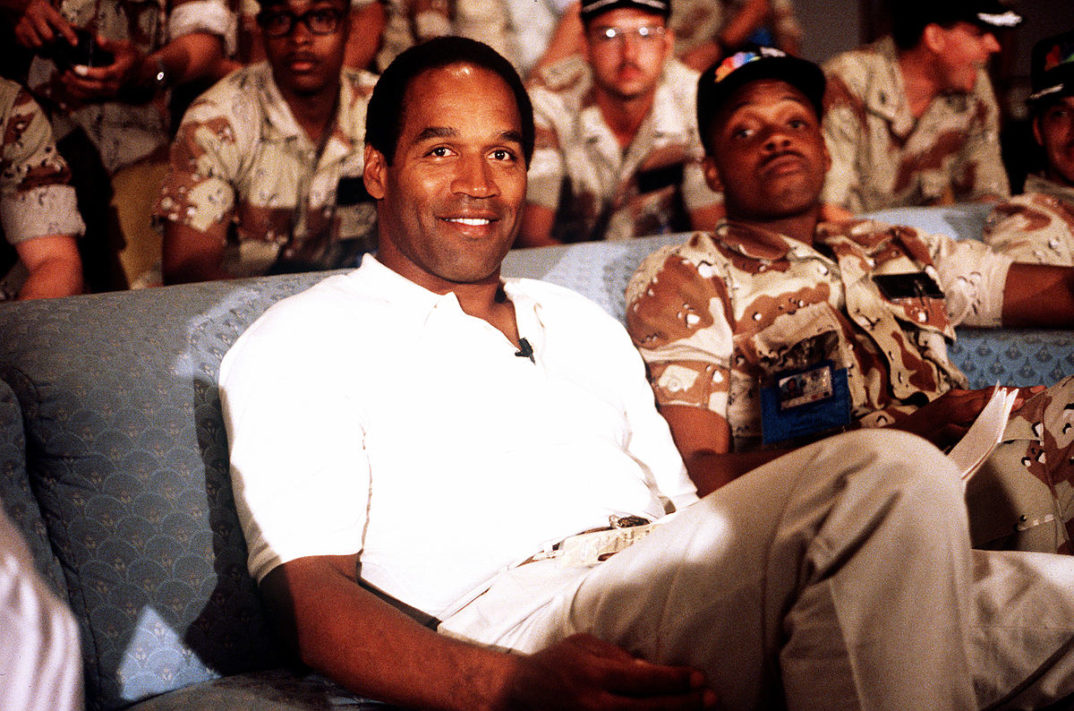

O. J. Simpson and the Complicated Legacy of Identity Politics

As I write these lines, I still do not know whether or not O. J. Simpson will be paroled. His hearing is scheduled for July 20. But, regardless of the outcome, a consideration of his life always invites ethical reflections.

By all accounts, Simpson deserves to be paroled. His behavior in prison has been exemplary, and no one is expected to testify against him at his parole hearing. Not much controversy is going on. The controversy, however, is about whether or not he deserved to go to prison in the first place. Most legal analysts believe that his sentence in 2008 was disproportionately harsh. While he was no doubt guilty of the armed robbery charges pressed against him, there was wide suspicion that this was just payback for having gotten away with murder previously.

This raises an important ethical question: if a murderer is declared not guilty by a flawed judicial system, does a judge have a moral obligation to disproportionately punish him for a later offense? Most ethicists believe that morality is a higher calling than legality. But, even then, it does not seem morally acceptable for someone to take justice into her own hands. To disproportionately punish a criminal now in order to correct a past injustice is not far removed from vigilantism. A society with vigilantism, no matter how just it may pretend to be, always ends up being even more unjust.

But, make no mistake: Simpson’s acquittal in his 1995 murder trial was thoroughly unjust. The injustice was not so much about whether or not Simpson was actually guilty, but rather, the way the judge allowed in his court irrelevant arguments that ultimately got Simpson off the hook. Robert Shapiro (one of Simpson’s attorneys) famously complained that his colleague, Johnny Cochran, unashamedly played the race card. If Jeffrey Toobin’s account in The Run of His Life is to be believed, this was sheer hypocrisy, as Shapiro himself was the one who came up with the idea that the jury should be manipulated with racial arguments, so that they would acquit Simpson.

Be that as it may, the fact is that, indeed, the race card was played, and it paid off. The evidence of Simpson’s guilt was overwhelming: DNA, witness’ testimonies, his suicide threat while he tried to escape from the authorities, his past history of domestic violence. Astonishingly, a few years after his acquittal, he even had a deal to write a book, If I Did It, theorizing how he would have killed his wife.

Yet, the jury decided to acquit him. There only seemed to be one explanation: race. The jury, overwhelmingly made up of black citizens, seemed to approach Simpson’s trial not so much as an investigation about whether or not the defendant killed two people, but rather, as an opportunity to defeat the white oppressive power that, only three years prior, had unjustly acquitted white policemen who brutally beat an innocent white man in Simpson’s own city, Los Angeles. So, very much as in Simpson’s disproportionate sentencing in 2008, his acquittal in 1995 was also payback time.

At the time, the Simpson verdict became one of the most divisive issues in race relations in America: white people overwhelmingly believed he was guilty, whereas black people overwhelmingly believed he was innocent. Black people in America apparently believed this was a great victory for them, and if it came at the expense of freeing a murderer, so be it.

In fact, it was no victory. The People Vs. O. .J. Simpson: American Crime Story (the recent TV series about Simpson’s trial) depicts a powerful scene in which, after the trial, black prosecutor Chris Darden confronts black attorney Johnny Cochran, telling him that Simpson’s acquittal achieved nothing: a murderer walked free, and racism will go on. We do not know if this conversation actually took place, but the words of Darden’s character became prophetic. More than twenty years later, white policemen throughout America kill unarmed black men, with even more impunity than before Simpson’s trial. The struggle against racism is about justice. It is not about letting murderers walk away, just because they happen to have the same skin color as oppressed people.

The new black generation in America seems to understand this, and at least tacitly, acknowledges its past error. Now, black people believe as much as whites that Simpson was guilty, after all. Yet, the harm had already been done. To a certain extent, Simpson’s trial was a contributing factor to the rise of the alt-right and white nationalism. In the mind of many white nationalists, the fact that most black people were willing to defend a murderer just because of his race convinced them that, indeed, whites are threatened by minorities.

And, ultimately, it paved the way for the rise of white identity politics. If black people played the race card during the Simpson trial, so their argument went, why can’t whites now play their own race card in politics? If the jury acquitted Simpson simply because he was black, why can’t someone vote for Trump, simply because he is white? O. J. Simpson’s trial was an early experiment in identity politics, and some civil rights leaders erroneously believed that this experiment would have good results. Today, with a white nationalist president, it has been proven that this experiment actually produced a monster.