The Gentrification of Hip-Hop

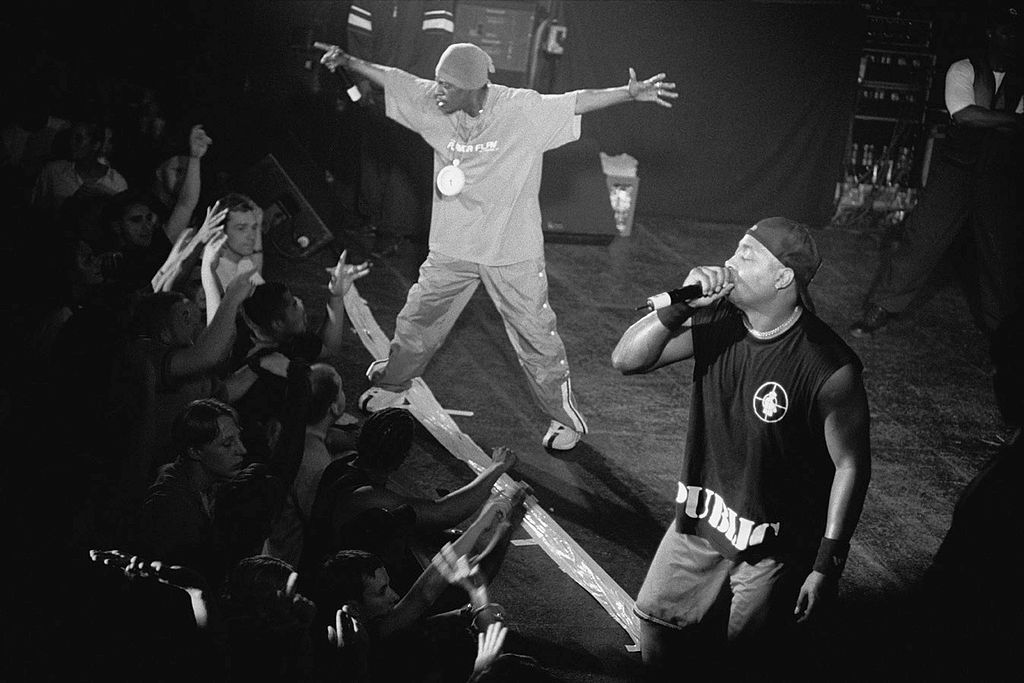

Hip-hop music began in the 1980s, and was primarily a means for African American communities to express commentary and frustration related to politics, discrimination, and common struggles often related to race relations. Crucially, music was being used to give voice to a people that has traditionally been suppressed or discounted because of the effects of systemic racism in the American political institution. One of the most significant groups to pioneer this genre was Public Enemy, whose music focused largely on sociopolitical commentary.

As the genre gained popularity, however, it became increasingly commercialized. To a certain extent, rap and hip hop artists have lost their creative ability to speak on matters of such importance, and are instead influenced by the industry to make music that is marketable to wider (and whiter) audiences. Lauren Carter of Rap Rehab argues that the purpose of hip hop has been skewed and twisted from its original intent by corporate control of the industry: “our ‘values’ have shifted from life-affirming qualities to a death program of promiscuity, anti-love, drug use, drug dealing, materialism, violence and criminality, and people who claim to love hip hop promote these ‘values’ every day.”

This is particularly problematic due to the fact that rap and hip hop music have become so popular among white audiences. This would not be as big of an issue if white fans of rap music put in the effort to understand the culture. However, because of the commercialization of the hip hop genre, the origins and true purpose of hip hop music is often overlooked or trivialized as themes of sex, drugs, and violence take the commercial forefront. Even rapper Iggy Azalea has been criticized for her controversial appropriation of black hip hop culture without adequately understanding what the culture is supposed to be about. (Most notably, she has been criticized for using a “blaccent,” leading some to compare her music to blackface minstrelsy).

Because hip hop has become more about sex, drugs, and violence than political commentary and social change in response to commercialization, systemic stereotypes that white people might hold of the African American community are reinforced. Without necessarily meaning to, a lot of modern-day hip hop music seems to imply (especially to white audiences) that negative stereotypes about African Americans must be true; why else would African American artists be singing and rapping about them? This is not to say that white people cannot listen to or enjoy hip hop music. They absolutely can, but it is also important that they make an effort to understand hip hop culture and the struggle from which it was born.

So where does the moral responsibility lie in combatting the gentrification of hip hop music? Certainly the individual artist could hold some responsibility in choosing what they rap about, though often the industry as a whole has more of a say in this than the artist. Additionally, it is not the responsibility of the oppressed to educate the privileged on why their social struggle is valid and important.

Some artists, however, are using their platform to promote socially conscious hip hop. Perhaps most notable is Beyoncé’s 2016 album, Lemonade. Lemonade is a documentary-style visual album, meaning that the music videos for each song, when played in succession, tell a true story. Through the powerful images and music on the album, Beyoncé highlights important themes of the Black Lives Matter movement, and cites multiple examples of ways in which African Americans are systematically oppressed. Some of the most powerful statement images throughout the work include pictures of the mothers of Michael Brown, Eric Garner, and Trayvon Martin, and allusions to the impact of racially and socially unequal infrastructure in New Orleans during Hurricane Katrina. Though widely successful and a powerful statement on the importance of women in the Black Lives Matter movement, Beyoncé did receive criticism from some white fans who missed the “old” Beyoncé, before she went “all political.”

This brings up two other agents of moral responsibility in this case: the music industry and white audiences. In marketing to whiter audiences, the industry has allowed negative stereotypes of African Americans to pervade, which counters everything for which hip hop culture was created to challenge. That being said, white audiences certainly also hold some responsibility in educating themselves on sociopolitical issues having to do with race. Though it is not inherently wrong for white people to listen to hip hop or rap music, it is crucial they understand its origins, and what it is supposed to represent, so they may be less and less influenced by negative stereotypes of African Americans which are exploited by the music industry.