For the second time in recent years, conservatorships are in the news. Like the many articles discussing Britney Spears’s, these accounts often highlight the ways the conservatorship system can be abused. News outlets focus on abuse for good reason, there are over 1.3 million people in conservatorship/guardianship in the United States, and those in such a position are far too often taken advantage of.

But there are other ethical concerns with conservatorship beyond exploitation. Even when a conservator is totally scrupulous and motivated merely by the good of their conservatee, there is still something ethically troubling about any adult have the right to make decisions for another. As Robert Dinerstein puts it, even when conservatorship “is functioning as intended it evokes a kind of ‘civil death’ for the individual, who is no longer permitted to participate in society without mediation through the actions of another.”

So, what is the moral logic underlying the conservatorship relationship? What are the conditions under which, even in principle, one should be able to make decisions for another person; and how exactly should we understand that kind of relationship? These are the questions I want to address in this post.

So What Is a Conservatorship?

Tribb Grebe, in his excellent explain piece, defines a conservatorship as “a court-approved arrangement in which a person or organization is appointed by a judge to take care of the finances and well-being of an adult whom a judge has deemed to be unable to manage his or her life.”

(You may sometimes hear conservatorships referred to as guardianship. Both the terms ‘conservatorship’ and ‘guardian’ are terms defined by legal statue, and while they usually mean slightly different things, what they mean depends on which state you are in. In Florida, a conservatorship is basically a guardianship where the person is ‘absent’ rather than merely incapacitated or a minor, while in other states a conservator and guardian might have slightly different legal powers, or one term might be used for adults and the other for minors. For most purposes, then, we can treat the two terms as synonymous.)

A conservatorship is, therefore, an unusual moral relationship. Normally, if I spend someone else’s money, then I am a thief. Normally, I need to consent before a surgeon can operate on me. — no one else has the power to consent for me.

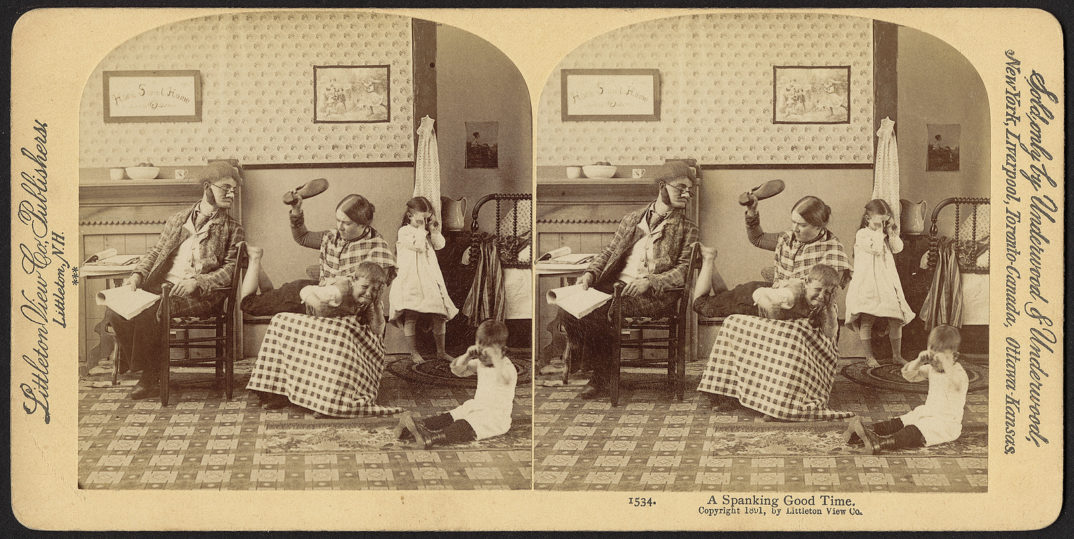

Or at least, conservatorship is an unusual relationship between two adults. It is actually the ordinary relationship between parents and children. If a surgeon wants to operate on a child, the surgeon needs the permission of the parents, not of the child. A parent has the legal right to spend their child’s money, as they see fit, for the child’s good. Conservatorship is, essentially, an extension of the logic of the parent-child relationship. To understand conservatorship, then, it will be useful to keep this moral relationship in mind.

Parents, Children, and Status

My favorite accounts of the moral relationship between parents and children is given by Immanuel Kant in his book The Metaphysics of Morals. Kant divides up the rights we have to things outside ourselves into three categories: property, contract, and status. Arthur Ripstein introduces these categories this way: “Property concerns rights to things; contract, rights against persons; and status contains rights to persons “akin to” rights to things.”

Let’s try to break those down more clearly.

Property concerns rights to things. For example, I have a property right over my laptop. I don’t need to get anyone else’s permission to use my laptop, and anyone else who wanted to use it would have to first get my permission.

There are two essential parts to property: possession and use.

Possession means something like control. I can open up my laptop, turn it on, plug it in, etc. I can exercise some degree of control over what happens to my laptop. If I could not, if my laptop were instantly and irrevocably teleported to the other end of the universe, I could not have a property interest in the laptop any longer. I would no longer have possession, even in an extended sense.

Use, in contrast, means that I have the right to employ the laptop for my purposes. Not only do I have some control over the laptop, I can also exercise that control most anyway I want. I can surf the web, I can type up a Prindle Post, or I can even destroy my laptop with a hammer.

Use is why my laptop is mine, even if you are in current control of it. If I ask you to watch my laptop while I go to the bathroom, then you have control of the computer, but you don’t have use of it. You don’t have the right to use the computer for whatever purpose you want. If you destroy the laptop while I’m away, then, you committed and injustice against me.

Contract involves rights to other people. If you agree to mow my lawn for twenty dollars, then I have a right that you mow my law. This does not mean that I have possession of you. You are a free person; you remain in control of your actions. So, in contract I have use of you, but not possession of you. I have a right that you do something for my end (mowing my lawn), but I am not in control of you even at that point. I cannot, for instance, take over your mind and guide your actions to force you to mow my lawn (even though I have a right that you mow my lawn).

This is one way in which contract is unlike slavery. A slaveowner does not just claim the use of their slave. They also claim control over the slave. In a slave relationship, the slave is no longer their own master, and so is not understood to have possession of their own life.

Of course, another difference between contract and slavery is that contract is consensual. But that is not the only difference. If the difference were simply that slavery was not consensual, then in principle slavery would be okay if someone agrees to become a slave. But Kant rejected that thought. Kant argued that a slavery contract was illegitimate, even if the slave had originally consented.

Status is the final relation of right, and it is status that Kant thinks characterizes parents and children. According to Kant, status is the inverse of contract. In contract, I have the use, but not the possession, of someone else. In status, I have the possession of another but not use.

What could that mean?

Remember that t to have possession of someone is to have a certain control over them. Parents have control over the lives of their children. Parents can, for instance, spend their children’s money, and parents can force their children to behave in certain ways. Not only that, but parents can do this without the consent of their children. These relationships of status, then, are very different from relations of contract.

But then why isn’t a parent’s control over their child akin to slavery?

To distinguish relations of slavery from relations of status, we need to attend to the second half of a status relationship. Parents have possession of their children, but they do not have the use of their children.

Let’s look at the example of money first. Parents have possession and use of their own money. That means parents controls their own money and have the right to spend it however they want. In contrast, parents have the possession, but not the use, of their children’s money. That means that while parents can control their own money, they cannot just spend it however the parent wants. Instead, parents can only spend the money for the good of the child. While I can give my own money away for no reason, I cannot give my child’s money away for no reason.

Parents have a huge amount of control over their children’s lives. However, Kant thinks that parents can only rightly use that control on behalf of their children. This does not mean that parents cannot require their children to perform chores. But it does mean that the reason parents must assign chores has to be for the moral development of the child. Kant was critical, for instance, of people who had children just so that they would have extra hands to help with work on a family farm. Because children cannot consent to the control that parents have, therefore, parents wrong their children if they ever use that control for their own good as opposed to the good of the child.

The Fiduciary Requirement

Parents, then, act as a kind of trustee of their child’s life; they are a fiduciary. The word ‘fiduciary’ is a legal word, which describes “a person who is required to act for the benefit of another person on all matters within the scope of their relationship.” As Arthur Ripstein notes, the fiduciary relationship is structurally parallel to the parental relationship.

“The legal relation between a fiduciary and a beneficiary is one such case. Where the beneficiary is not in a position to consent (or decline to consent), or the inherent inequality or vulnerability of the relationship makes consent necessarily problematic, the fiduciary must act exclusively for the benefit of the beneficiary. It is easier for the fiduciary to repudiate the entire relationship by resigning than for a parent to repudiate a relationship with a child. But from the point of view of external freedom the structure is exactly the same: one party may not enlist the other, or the other’s assets, in support of ends that the other does not share.”

This is a powerful explanatory idea, and recognizing these fiduciary relationships helps us explain various forms of injustice. For example, since in a fiduciary relationship one is only supposed to act for the good of a trustee, this can be used to explain what is unjust about insider trading. If I use my position in a company to privately enrich myself, then I am abusing my office in the company. The private knowledge I have as an employee is available to me for managing the affairs of the company. To use that knowledge for private gain is to unjustly use the property of someone else.

This relationship can also help us understand political corruption. The reason it is unjust for presidents to use their office to enrich themselves, is because their presidential powers are given for public use for the sake of the nation. To manage the government for private purposes is to unjustly mismanage the resources entrusted to the president by the people.

Why Status

But even if we know the sort of relationship that obtains between parents and children — a type of fiduciary relationship — we still need to know why such a relationship is justified. After all, I can’t take control of your life, even if I use that control for your own good. I can’t do so even if I am wiser than you and would make better decisions than you would yourself. Because your life is your own, you have possession of your own life, not matter how much happier you would be if I took control.

The reason why parents have possession of their children is not that parents are wiser or smarter than their kids. Instead, it is because Kant thinks that children are not yet fully developed persons. Children because of the imperfect and still developing position in which they find themselves, are not able to be in full control of themselves (for a nice defense of this view of children see this article by Tamar Schapiro). Of course, the legal relationships here are crude. It is not as though the moment someone turns 18 they instantly pass the threshold of full moral personhood. Growing up is a messy process, and this is why parents should give children more and more control as they mature and develop.

Conservatorship

And just as the messiness of human development means that people should often have some control over their lives before they reach the age of 18, so too that messiness means that sometimes people must lose some control over even after they reach adulthood.

Just as children are not fully developed moral persons, so someone with Alzheimer’s is not a fully developed moral person. We appoint a conservator over someone with Alzheimer’s not because the conservator will make better choices, but because people with Alzheimer’s are often incapable of making fully developed decisions for themselves.

This, then, is the basic moral notion of conservatorship. A conservator has possession but not use of their charge. They can make decisions on their behalf, but those decisions have to be made for the charge’s good. And such a relationship is justified when someone is unable to be a fully autonomous decision-maker, because in some way their own moral personhood is imperfect or damaged.