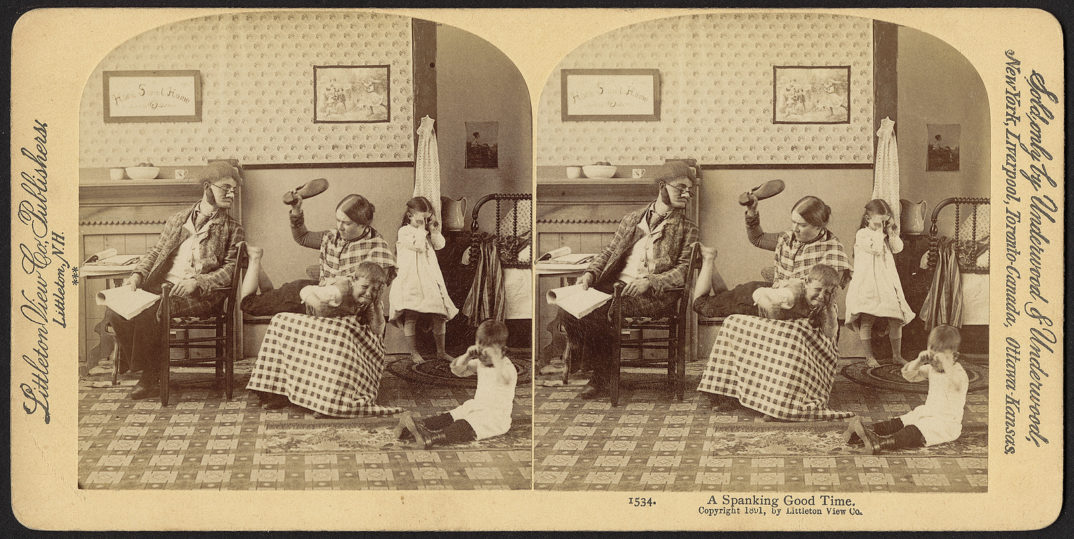

Scotland May Ban Spanking. Should the United States?

An October 19, 2017 article in The Scotsman reported that the Scottish Government plans to implement proposals that would “remove the defence of “justifiable assault” from Scottish law, which can currently be used by parents who use corporal punishment on their children. Late last year, France also instituted a law banning the spanking of children. This made it the 52nd country to do so.

The United States is not on that list of countries. According to an NBC News report from 2014, corporal punishment is legal in all 50 US states. State statutes generally indicate that the physical punishment must be “reasonable” or “not excessive.” In addition, 19 states still allow corporal punishment in schools, as of 2014. Public opinion in the United States also widely supports spanking. The NBC News report cited a 2013 Harris Poll which found that 81 percent of Americans say “parents spanking their children is sometimes appropriate.”

Often in moral reflection, it is useful to reason by way of analogy. Sometimes violent intrusions on a child’s bodily integrity is clearly justified (even if the child does not consent to it). We often take our children to the doctor to receive vaccinations that, when administered, cause acute pain. Most young children are not exactly eager to go to the doctor to receive these shots. Why, then, are we justified–perhaps even obligated–to do this to our children against their will? Because we have good reason to believe that the benefits of vaccination outweigh the harms of vaccination. Given that children are not cognitively mature enough to make good decisions in their own long-term interest, parents–and sometimes the state–are justified in forcing those decisions on them. Likewise, spanking cannot be ruled out, in principal, as morally unjustifiable. If empirical evidence shows that spanking as a disciplinary strategy can produce behavioral benefits for some children, the spanking might be morally permissible in certain circumstances.

This framework places the locus of debate about spanking in the realm of the social sciences–sociology and developmental psychology. Unfortunately, currently available empirical evidence concerning the potential harms and benefits of spanking children, is not clear cut. As cited on Vox, A relatively recent 2016 meta-analysis of studies conducted on spanking concluded that there is “no evidence that spanking is associated with improved child behavior.” However, this meta-analysis has also been called into question by reputable organizations. The American College of Pediatricians wrote an editorial criticizing the analysis for relying on correlational evidence “that would be considered woefully inadequate in any other scientific field.” In addition, the studies that provided the data for the meta-analysis did not all use the same definition of what behaviors constituted spanking. As such, the credibility of the meta-analysis is reasonably in doubt. The problem is that ethical norms themselves prevent us from using traditional experimental methods to understand spanking. Randomly assigning a group of children to be spanked in order to study the effectiveness of spanking would violate traditional ethical guidelines in human experimentation.

Worth considering, then, is which side of the argument has the responsibility for providing the burden of proof. Conservatively, we might say that the current weight of empirical evidence neither supports spanking as an effective form of discipline nor conclusively shows spanking (at least mild forms) to have long-term negative effects on a child’s psychology. As such, one might argue that it would be best to err on the side of not condoning physically violent actions. That is, there is a moral presumption against physically hurting a non-consenting child, unless good reasons can be given to override the presumption. Consider the vaccination example, again. Imagine that empirical research had not conclusively shown that vaccination has positive health effects. Parents would not be justified in sticking their children with painful needles, if they didn’t know such actions would help them.

Like in many moral issues, there is a difference between the personal morality of spanking and the appropriate public policies towards spanking. Whether or not spanking is immoral does not necessarily determine if the government should ban it. From the perspective of public policy, one might argue that the responsibility for providing the burden of proof lies on the government to show conclusively that spanking is harmful before banning it. Why? As evidenced in public opinion polling and the current state of law, spanking is well ingrained in American culture (though it may be more prevalent in some parts of the country than others). How someone parents their kids is as personal and private as nearly anything else they do in life. Liberal governments that put a premium on protecting individual liberty must tread lightly when intruding on this personal/private sphere. As such, it may be both politically wise and reasonable from the perspective liberal tolerance to emphasize methods of public persuasion over legal intervention if the goal is to reduce overall the use of spanking as a disciplinary method.