Since moving to upstate NY in 2018, I’ve become a pretty keen Buffalo Bills fan. And now $850 million of public money is being invested into a new stadium for them – though the Bills are not the only team to benefit from public funds.

Should we really be using tax dollars for such frivolities as sport? Why should billionaire team owners receive public money? Why should taxpayers fund private sports stadiums when, despite long-held opinion, they do not seem to have the expected economic benefit for the local area?

I think the key response here is to note that money should not be governments’ only concern. No doubt the Bills are a source of “civic pride.” Sports teams play an important role in many communities. Erin Tarver has argued that fandom can be an important part of a person’s identity. It can bind us together in communities, where thousands of people are cheering for one team – united by nothing more than a shared love for their team. Even fans of perpetual losers benefit (perhaps more so: a recent study suggests that fans of unsuccessful teams are more tightly bonded to one another than fans of more successful clubs. Good news for Bills fans.)

These connections are deep and important to many people. Andrew Edgar goes so far as to argue that these teams are akin to sacred objects for many of us. Kyle Fruh, Alfred Archer, and I have used this to argue that this means that when owners abuse the club, they’re doing something wrong: they’re trashing something of important cultural value.

This puts obligations on owners. For one, this lets us say that when the Bills owners were threatening to relocate the team they were doing something more than simply considering moving their business.

Finding a new home for the Bills would not just mean that some folks lost their jobs, it would mean that the focal point of this fan community was being ripped away. Something sacred was being destroyed.

It also seems to me that this places an obligation on local governments (in this case, New York State and Erie County). No doubt the Bills are very important to Buffalo and the surrounding area. To take a personal observation: if you go outside at 1pm on a Sunday in Rochester – an hour or two away from Buffalo – you won’t see many people. Everyone is watching the Bills.

Now, New York State spends over a hundred million dollars on arts funding every year. This is a good thing, but it seems like snobbery if we are to say that these important cultural things deserve state spending but football does not. (We can haggle over the amount it is fair to spend!)

So, if we should spend government money on cultural objects, we can make a reasonable case for spending money on the Bills stadium because the Bills are an important cultural object. Even if there will be no great economic benefit, New York State is right to invest if it helps preserve something culturally important.

Yet that only speaks to the general principle of using public money to fund private enterprise when it comes to sports stadiums – there are plenty of other reasons why we might object to funding the new Bills stadium.

Here is one objection: there are lurking objections about how much money governments should spend on cultural objects. Part of the point of the recent Just Stop Oil protest that doused (the glass in front of) a van Gogh with paint was to highlight our reactions. People seem to care more about art than they do about people being unable to heat their homes or buy food. No doubt there is something to this, but I think most people would agree governments should spend some money on things that help to enhance our lives, even if there are other pressing concerns.

Still, this investment can seem perverse, especially when, as Shalise Manza Young has pointed out, you look at the conditions poor people need to meet in order to get state assistance. Why should the rich owners of the Bills get state money when people starve and Buffalo, like much of upstate New York, has racially-driven poverty problems?

Now, I do not know how the deal is financed, but one solution here would be to make clear that the money is for the Bills, not for their owners. Or, we can see it as a joint-investment between the state and the owners into Western New York, rather than a payment that will just benefit these owners. Otherwise, critics are right when they say New York is “using public money for private business ventures, especially for the benefit of wealthy owners like the Pegulas.”

Sustaining important cultural objects is a worthwhile goal for governments, but lining the pockets of modern-day oil barons is not.

Whether this is a matter of the optics of the Bills stadium deal, or whether the deal simply does benefit the wealthy Pegula family without being too concerned with what should matter – the cultural benefit of the Bills – is an important question, and I don’t have the answers!

Beyond that, we need to look at the investment in terms of a public good outside of sports. One criticism is that by building the new stadium next to the current one in the suburb of Orchard Park (which is nearly 95% White and has a 2020 median income of nearly $90,000) rather than Buffalo (which is less than 50% White and has a 2020 median income of just under $40,000), the state is failing to invest in communities that have been under-invested in for far too long and continuing to perpetuate racial injustices.

We also need to ask whether it helps to create goods, like more walkable communities? Does it help to improve public transit? Well, no, because it’s going to be built outside of the City of Buffalo and will inevitably come with the sprawl of parking lots that accompany NFL stadiums.

There are even sporting criticisms: this stadium will never host a Superbowl, because it doesn’t have a roof – in Buffalo. Even setting aside Superbowl games, there is always the chance for some terrible weather to really disrupt a game – and that isn’t something the Bills should risk, what with Josh Allen leading what is likely to be a long-term force in the NFL.

And that is to say nothing of the potential corruption involved, nor of the fact money is being taken from Native Americans and isn’t being invested back into Native communities. My sense here is that the money was an effort to make sure that the Bills stayed in Buffalo – or, rather, Orchard Park. It is money that should be spent to keep the Bills around, but it is far from clear to me that this money is truly for the people of Buffalo, and this investment seems to fail to achieve a raft of other worthwhile goals that any such ambitious project should aim at.

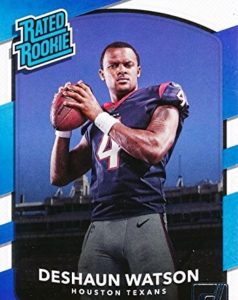

Deshaun Watson, the NFL quarterback who recently moved to the Cleveland Browns in a $230 million deal, has been credibly accused of sexual harassment or assault by 24 massage therapists. These allegations are not new: at the time that the Browns signed him this summer, there were

Deshaun Watson, the NFL quarterback who recently moved to the Cleveland Browns in a $230 million deal, has been credibly accused of sexual harassment or assault by 24 massage therapists. These allegations are not new: at the time that the Browns signed him this summer, there were