When it comes to climate change, defining the limits of reasonable skepticism is not only a matter of intellectual curiosity, but also moral and political urgency. In contemporary scientific circles, skepticism is generally celebrated as a virtue. However, those who reject the near-consensus about anthropogenic climate change also claim the “skeptic” title. This raises an important question: What does it mean to be skeptical, and when is skepticism no longer praiseworthy?

Philosophers have often pondered the extent of human knowledge. Skeptics argue that our understanding is more limited than we tend to believe. Some skeptics even claim that we can never know anything, or that none of our beliefs are justified and we ought to suspend all judgment on all issues.

Many climate scientists claim the title “skeptic” for themselves and attach the label “denier” to their opponents. The Committee for Skeptical Inquiry, for example, has called on the media to stop using the term “skepticism” to refer to those who reject the prevailing climate consensus and to instead use the term “denial.” We can, according to Washington and Cook, authors of Climate Change Denial: Heads in the Sand, think of the difference like this: “Skepticism is healthy both in science and society; denial is not.” However, when it comes to climate change, the term “skeptic” continues to be associated with those who reject the prevailing scientific consensus, blurring the line between skepticism and denial.

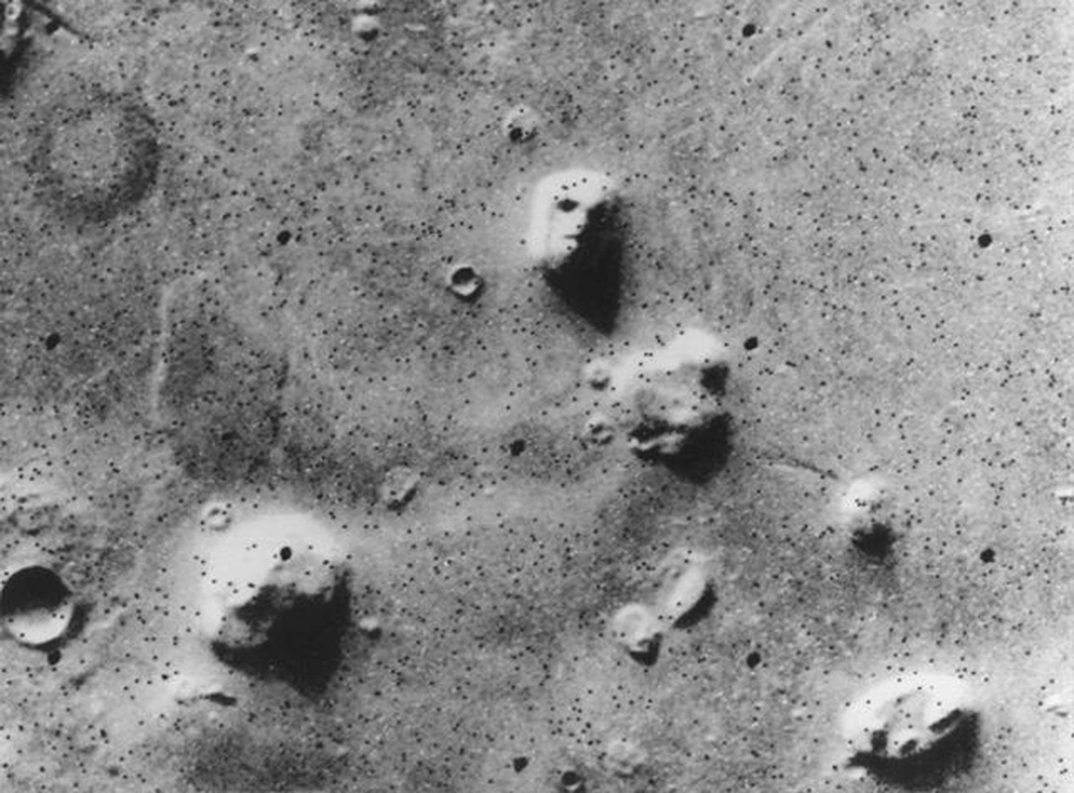

To better understand the differences between skepticism and denial, let’s consider a concrete example: the existence of ghosts. A ghost skeptic denies that we are justified in believing that ghosts exist. They neither believe nor disbelieve in ghosts, as they think there isn’t enough evidence to justify a belief in ghosts. A ghost denier, conversely, decidedly believes that ghosts do not exist. They disbelieve in ghosts, arguing that ghosts are incompatible with our best understanding of how the laws of the universe work, and that, absent good evidence for ghosts, we should conclude they do not exist. In general, it is not necessarily better to be a skeptic than a denier. Whether we ought to disbelieve something or merely suspend judgment depends on the particular issue and the strength of the evidence we have.

So why do Washington and Cook think that denial is always a bad thing? Ultimately, they are referring to a very specific sense of “denial.” They mean someone who clings “to an idea or belief despite the presence of overwhelming evidence to the contrary.” This is a sense of denial that draws on Freudian psychoanalysis, which characterizes denial as a pathological defense mechanism that involves denying something because one wishes it weren’t true. Denial in this sense is the result of some kind of emotional or psychological incapacity to accept reality.

It is clearly bad to be a climate change denier, or any kind of denier, in the pathological sense Washington and Cook have in mind. However, we can’t assume everyone who denies the scientific consensus on climate change is suffering from a psychological disorder. Some genuinely believe the evidence they have seen does not justify a belief in anthropogenic climate change. Whether it is a mistake to disbelieve in man-made climate change depends entirely on the strength of the scientific evidence. In my own view, the scientific evidence of anthropogenic climate change is very strong and this, rather than some psychological defect, is what makes denial inappropriate.

However, it is worth noting that most of those who reject the consensus on climate change identify as “skeptics” rather than “deniers,” claiming that they have not yet formed a conclusion on the matter. But plenty of scientists who defend the prevailing view on climate change also think of themselves as still embracing skepticism. This raises the question: who is the real skeptic?

To answer that question, we first need to understand a distinction between philosophical skepticism and the scientific skepticism advocated by figures like Michael Shermer, publisher of Skeptic magazine. Shermer defines skepticism as striking the “right balance between doubt and certainty.” As William James notes, this contrasts with a philosophical skeptic who says, “Better go without belief forever rather than believe a lie!” Philosophical skeptics only think we should believe things that are absolutely certain. Scientific skeptics try to believe whatever the evidence suggests has a greater than 50% chance of being true. These are very different standards. To philosophers, scientific skepticism is just “evidentialism” – the principle that our beliefs should be based solely on available evidence.

So who are the real skeptics? Perhaps some climate skeptics are philosophical skeptics. Perhaps they think it is more likely than not that anthropogenic climate change is real, but that we still aren’t justified in believing it. In this case, climate skeptics might be the “real skeptics,” but only on an interpretation of skepticism that most scientists would think is deeply objectionable.

But most climate skeptics are not philosophical skeptics. As the philosophers Coady and Corry observe, the debate between climate change proponents and climate skeptics is not a dispute between two groups of skeptics, one scientific and one philosophical. Instead, it is a disagreement between two groups of evidentialists, who differ in their interpretations and evaluations of the evidence and hence in their beliefs. Of course, one side must be wrong and the other must be right. But both sides appeal to the evidence, as they see it, to justify their respective views.

Proponents of anthropogenic climate change often accuse climate skeptics of disregarding the wealth of evidence supporting their stance. Conversely, climate skeptics argue that climate change advocates are swayed by personal desires, emotions, or political ideologies. But, at bottom, both criticisms reveal a shared commitment to evidentialism. These are accusations of forming beliefs based on things other than the best available evidence – of violating evidentialism. Neither side of the climate debate adopts the extreme skeptical position of suspending all judgment and belief, regardless of the evidence at hand.

Acknowledging that most people on both sides of this issue are committed to an evidentialist approach is crucial, because it encourages both sides to engage in a constructive dialogue that focuses on the merits of proof, rather than resorting to ad hominem attacks or accusations of bias. By emphasizing the importance of evaluating the strength and reliability of the evidence, it becomes possible to move beyond the polarizing and confusing labels of “skeptic” and “denier” and engage in a more fruitful discussion. Perhaps this could help reverse the current trend in public opinion toward climate skepticism.

Given that both sides of the climate change debate are committed to evidentialism, instead of squabbling over the label “skeptic,” which neither side should want to claim given its philosophical meaning, our focus should return to simply assessing the facts.