Life on Mars? Cognitive Biases and the Ethics of Belief

In 1877 philosopher and mathematician W.K. Clifford published his now famous essay “The Ethics of Belief” where he argued that it is ethically wrong to believe things without sufficient evidence. The paper is noteworthy for its focus on the ethics involved in epistemic questions. An example of the ethics involved in belief became prominent this week as William Romoser, an entomologist from Ohio claimed to have found photographic evidence of insect and reptile-like creatures on the surface of Mars. The response of others was to question whether Romoser had good evidence for his belief. However, the ethics of belief formation is more complicated than Clifford’s account might suggest.

Using photographs sent by the NASA Mars rover, Romoser has observed insect and reptile like forms on the Martian surface. This has led him to conclude, “There has been and still is life on Mars. There is apparent diversity among the Martial insect-life fauna which display many features similar to Terran insects.” Much of this conclusion is based on careful observation of the photographs which contain images of objects, some of which appear to have a head, a thorax, and legs. Romoser claims that he used several criteria in his study, noting the differences between the object and its surroundings, clarity of form, body symmetry, segmentation of body parts, skeletal remains, and comparison of forms in close proximity to each other.

It is difficult to imagine just how significant the discovery of life on other planets would be to our species. Despite all of this, several scientists have spoken out against Romoser’s findings. NASA denies that the photos constitute evidence of alien life, noting that the majority of the scientific community agree that Mars is not suitable for liquid water or complex life. Following the backlash against Romoser’s findings, the press release from Ohio University has been taken down. This result is hardly surprising; the evidence for Romoser’s claim simply is not definitive and does not fit with the other evidence we have about what the surface of Mars is like.

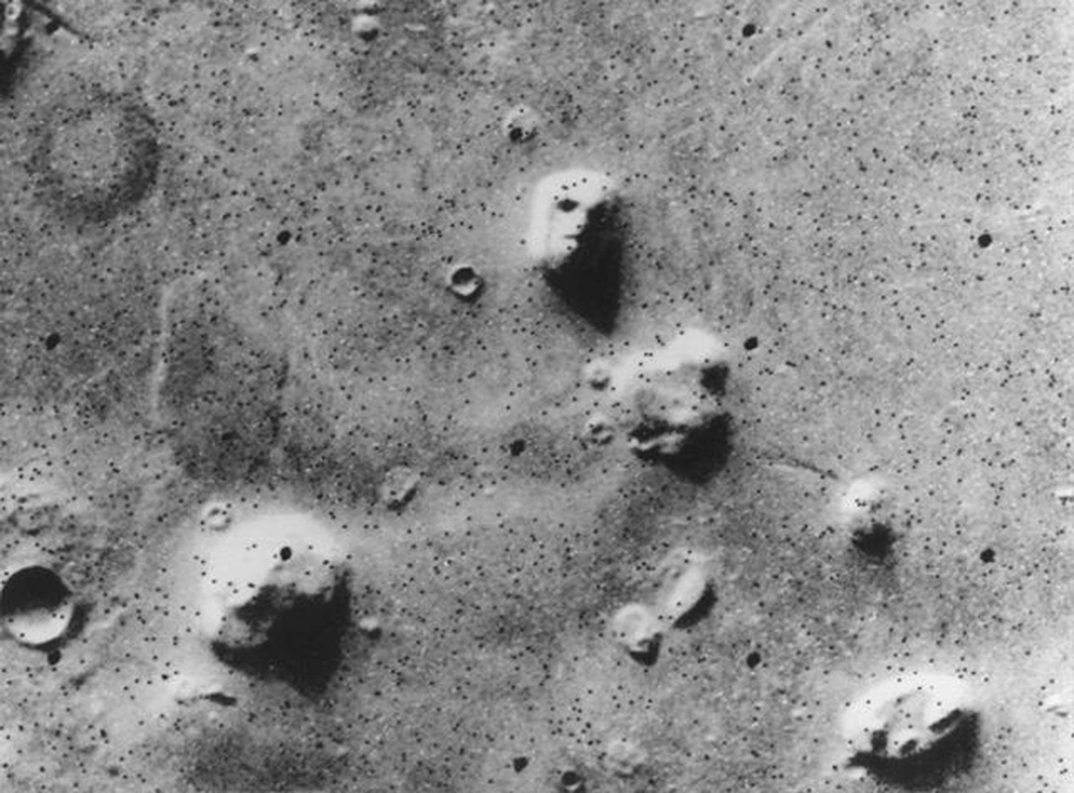

However, several scientists have offered an explanation for the photos. What Romoser saw can be explained by pareidolia, a tendency to perceive a specific meaningful image in ambiguous visual patterns. These include the tendency of many to see objects in clouds, a man in the moon, and even a face on Mars (as captured by the Viking 1 Orbiter in 1976). Because of this tendency, false positive findings can be more likely. If someone’s brain is trained to observe beetles and their characteristics, it can be the case that they would identify visual blobs as beetles and make the conclusion that there are beetles where there are none.

The fact that we are predisposed to cognitive biases means that it is not simply a matter of having evidence for a belief. Romoser believed he had evidence. But various cognitive biases can lead us to conclude that we have evidence when we don’t, or to dismiss evidence when it conflicts with our preferred conclusions. For instance, in her book Social Empiricism Miriam Solomon discusses several such biases that can affect our decision making. For example, one may be egocentrically biased toward using one’s own observation and data over others.

One may also be biased towards a conclusion that is similar to a conclusion from another domain. In an example provided by Solomon, Alfred Wegener once postulated that continents move through the ocean like icebergs drift through the water based on the fact that icebergs and continents are both large solid masses. Perhaps in just the same way Romoser was able to infer based on visual similarities between insect legs and a shape in a Martian image, not only that there were insects on Mars, but that the anatomical parts of these creatures were similar in function to similar creatures found on Earth despite the vastly different Martian environment.

There are several other forms of such cognitive biases. There is the traditional confirmation bias, where one focuses on evidence that confirms their existing beliefs and ignores evidence that does not. There is the anchoring bias, were one relies too heavily on the first information that they hear. There is also the self-serving bias, where one blames external forces when bad things happen to them, but they take credit when good things happen. All of these biases distort our ability to process information.

Not only can such biases affect whether we pay attention to certain evidence or ignore other evidence, but they can even affect what we take to be evidence. For instance, the self-serving bias may lead one to think that they are responsible for a success when in reality their role was a coincidence. In this case, their actions become evidence for a belief when it would not be taken as evidence otherwise. This complicates the notion that it is unethical to believe something without evidence, because our cognitive biases affect what we count as evidence in the first place.

The ethics of coming to a belief based on evidence can be even more complex. When we deliberate over using information as evidence for something else, or whether we have enough evidence to warrant a conclusion, we are also susceptible to what psychologist Henry Montgomery calls dominance structuring. This is a tendency to try to create a hierarchy of possible decisions with one dominating the others. This allows us to gain confidence and to become more resolute in our decision making. Through this process we are susceptible to trading off the importance of different pieces of information that we use to help make decisions. This can be done in such a way where once we have found a promising option, we emphasize its strengths and de-emphasize its weaknesses. If this is done without proper critical examination, we can become more and more confident in a decision without legitimate warrant.

In other words, it is possible that even as we become conscious of our biases, we can still decide to use information in improper ways. It is possible that, even in cases like Romoser, the decision to settle in a certain conclusion and to publish such findings are the result of such dominance structuring. Sure, we have no good reason to infer the fact that the Martian atmosphere could support such life, but those images are so striking; perhaps previous findings were flawed? How can one reject what one sees with their own eyes? The photographic evidence must take precedence.

Cognitive biases and dominance structuring are not merely restricted to science. They impact all forms of reasoning and decision making, and so if it is the case that we have an ethical duty to make sure that we have evidence for our beliefs, then we also have an ethical duty to guard against these tendencies. The importance of such ethical duties is only more apparent in the age of fake news and other efforts to deliberately deceive others on massive scales. Perhaps as a public we should more often ask ourselves questions like “Am I morally obliged to have evidence for my beliefs, and have I done enough to check my own biases ensure that the evidence is good evidence?”