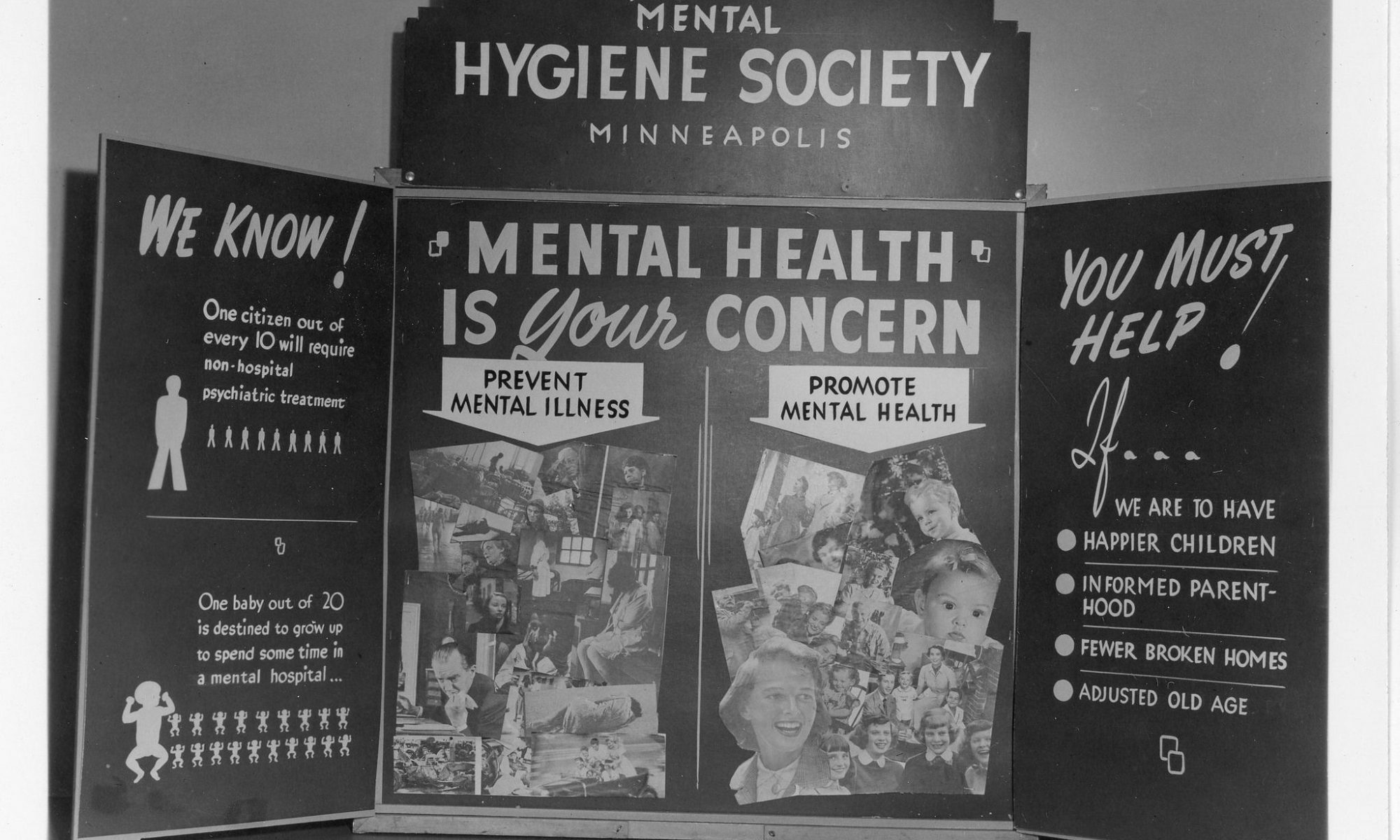

The concept of self-care, as of late, has gained a kind of cultural omnipresence. Originating in the context of healthcare, self-care was, at first, used to describe the ways in which patients with chronic illness might work to improve their physical health: a balanced diet, regular exercise, and the like. But having grown beyond this strictly clinical context, self-care is now something much more: for students and teachers; for parents and children; for business owners and employees; for HR professionals and for anti-capitalists. Self-care has even circled back on its origins: it is no longer just something for people who are receiving healthcare, but — in the light of a crisis of mental health among nurses, physicians, and medical students — also for those who provide it.

Self-care is, of course, something which is deeply important: there’s a reason, after all, that the medical community has emphasized self-care for over 50 years, and that well-meaning friends will advise you to care for yourself when they see that you aren’t. But for all of the self-care advice which you might encounter — to go on walks, to journal, to take a bubble bath, or read a book — ubiquity has not brought the concept of self-care clarity.

In my first week of medical school, we frequently encountered talk of self-care. In PowerPoint presentations, we were told to prioritize diet, exercise, and time with our families. We were told to remember to drink water; we were invited to guided yoga sessions and optional lectures on mindfulness. When a panel on physician wellness was held, we were told that what we were doing was hard, but that it got better: we just needed self-care — to meditate or keep a mental health journal — in the meantime.

In your own professional context, you’ve likely heard similar advice, whether it be from a teacher, professor, or boss. This advice, however, admits to a specific understanding of what it means to care: namely, one which is reactive. Self-care is most frequently emphasized in environments which are inherently stressful: our classrooms, where students face exams and social pressures, and our places of work, where failing to meet expectations can deeply impact both you and your loved ones. Much of the same can be said of medical school, where advice on self-care was a theme of the first week precisely because it would be required the week after. Across these contexts, self-care is a kind of coping strategy: a way to deal with the hardships which we will encounter in our day-to-day lives.

This picture of what it means to care for oneself, however, is simply incomplete. While self-care is an important tool for dealing with stress, human flourishing involves more than just coping. Really caring for someone — including yourself — means not just being reactive, but also proactive: it means not just finding strategies for dealing with stressors, but also seeking to thrive. Self-care advice, however, is primarily oriented towards the former rather than latter: we use self-care as a way to cope, and much less often as a way to flourish.

A large part of this likely comes from the emphasis on self-care in educational and professional contexts. Self-care, in these spaces, is a means to an end: even if you’re fortunate enough to have a teacher or boss which truly cares about your thriving, self-care is emphasized insofar as it facilitates productivity. This is why appeals to self-care can strike a student or employee as shallow, or even unserious: in many classrooms and workplaces, self-care isn’t really for you, but for the sake of the organization. And, further, students and employees know what would likely happen if their self-care was oriented more towards their thriving rather than their productivity: self-care cannot interfere with attendance or the satisfaction of expectations. Here, we can see how reactive self-care benefits our institutions, while proactive self-care, sometimes, does not.

I don’t blame us for our focus on reactive self-care. Many don’t even have the privilege to think reactively about self-care, let alone proactively. But this raises an important point. Self-care is, obviously, something which you do — self-care places the burden of both reactive and proactive care solely on your shoulders. Human flourishing, though, is rarely something which can be understood in such solitary terms. Self-care emphasizes the self, and fails to acknowledge the fact that your well-being is, in large part, context-dependent: the expectations placed on you at work and school, and the stressors you encounter there, will affect your well-being. A single-minded focus on self-care, then, can separate cause from effect, and direct our attention towards stabilizing our well-being rather than the reasons our well-being is poor: it is an incredibly effective tool for shifting the entire responsibility for one’s poor well-being entirely onto the individual, rather than the environment (the school, workplace, or society) which most likely bears some of the blame. Your school may emphasize self-care in the classroom, but ignore the bullying which makes you need self-care in the first place. Your workplace may offer classes on meditation, but if your self-care conflicts with your productivity, your boss will likely find someone who prioritizes the latter. If self-care is to truly be a form of care, then, it cannot rely entirely on the self, nor can it abstract the self from its context — and the fact that, at some level, our institutions have an obligation to care for us as well.

If we take these observations seriously, our acts of self-care will point towards us in a radically different direction. Self-care is not about struggling to keep one’s head above water: self-care is about the pursuit of thriving, and the transformation of our institutions in a way which fosters that thriving. It also challenges us to think about our obligations to others: the ways in which we burden others with their own care, rather than lifting that burden ourselves. Human thriving is complex and communal, and relies on more than bubble baths and journaling; but if we seek ways to truly care for ourselves and others, we work towards something which is much more meaningful.