From the Cuckoo’s Nest to the Jailbird: What’s Happening to the Mentally Ill in America?

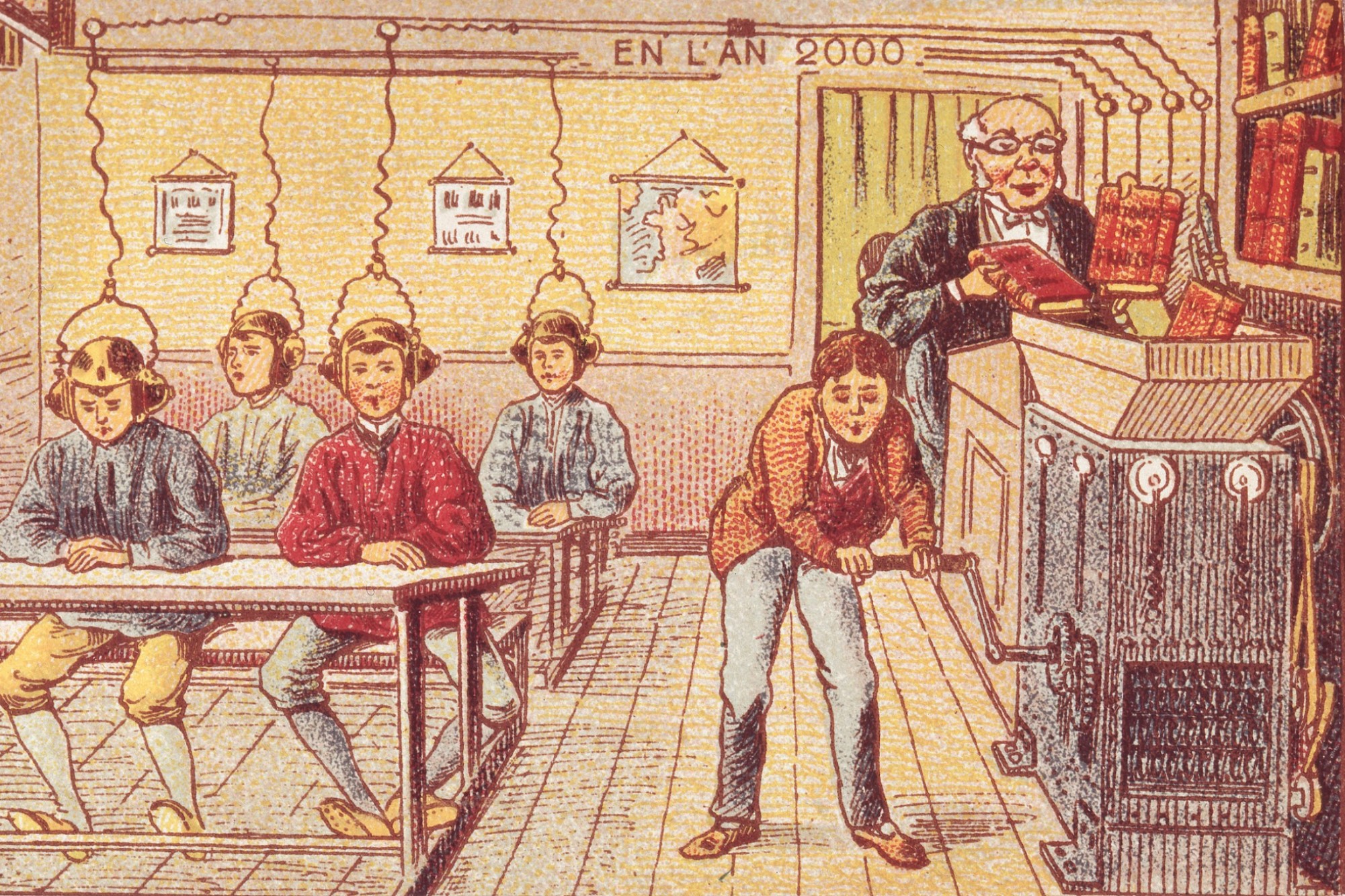

The history of mental illness is riddled with what are now horror stories: mental illnesses “treated” by bleeding patients with leeches, dousing them with hot or cold water, or simply putting them to death. From the 1600s to the 1800s in Europe and in the newly established United States, it was common for mentally ill people to be locked away in asylums, sometimes chained to the walls in what were essentially dungeons. Movements in the 1800s by activists like Philippe Pinel in France and Dorothea Dix in the northeastern states of the US helped to change these dungeons into what better resembled hospitals, with more comfortable housing and medical doctors.

However, the numbers of mentally ill people who were institutionalized continued to grow. Shortly after the number of institutionalized mentally ill Americans peaked in 1955, with 560,000 hospitalized patients, a popular book was published called One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest. The author, Ken Kesey, based his story on his experiences working in a psychiatric ward, and the book is known for painting the patients as not truly ill, but kept isolated from society because they do not behave in accordance with social norms. This popular book was released right before a mass deinstitutionalization took place in America, sparked by the negative opinions of the public towards mental hospitals and the advent of effective psychiatric drugs.

This may sound like the beginning to a happy ending for our country’s mentally ill population, released from undesirable mental hospitals and provided with a cure. However, this did not turn out to be the case. With the deinstitutionalization of the mentally ill came a dramatic decrease in the number of psychiatric hospitals available. However, our present day mentally ill population finds itself institutionalized yet again—this time not in a hospital. In 2008 it was estimated that about 10% of the 2,310,984 prisoners in United States prisons had severe mental illnesses. A 1992 survey of American jails found that many of these inmates are held without charges, simply awaiting a bed in a psychiatric hospital.

Not all those suffering from mental illnesses are incarcerated: about one-third of all homeless people are considered seriously mentally ill; most of these suffer from schizophrenia. Why has the process of deinstitutionalization led to such a sorry state of affairs? Part of the reason is that advocates for deinstitutionalization in the 60s envisioned mentally ill individuals seeking out their own treatment when they needed it at community-based mental health service providers, and having the resources to continue their treatment as directed. In reality, some people with mental illnesses may not be amenable to treatment, and some may wish to seek treatment but find that it is too costly—even if they are insured.

The truth of the matter is that there is a need for more institutions that are actually equipped to house and help those with mental illnesses—homeless shelters and prisons are not sufficient for this purpose. We certainly do not wish to return to the mental institutions of old, but surely we can create affordable mental hospitals that balance quality care and personal freedom. It would be a more efficient use of the approximate $15 billion a year that American taxpayers pay to house people with psychiatric disorders in prisons.