Mental Health, Information Literacy and the Slenderman Stabbing Case

On May 31, 2014, two 12-year-old girls lured a friend, also 12, into the woods with the promise of a game of hide-and-seek. Once there, one of the girls pinned their friend down, while the other stabbed her 19 times with a long-bladed kitchen knife, causing serious injuries to major organs and arteries. The young perpetrators then fled the scene, leaving their young friend to die of her injuries. Miraculously, the victim survived. She was able to crawl to a road where a cyclist found her and went for help.

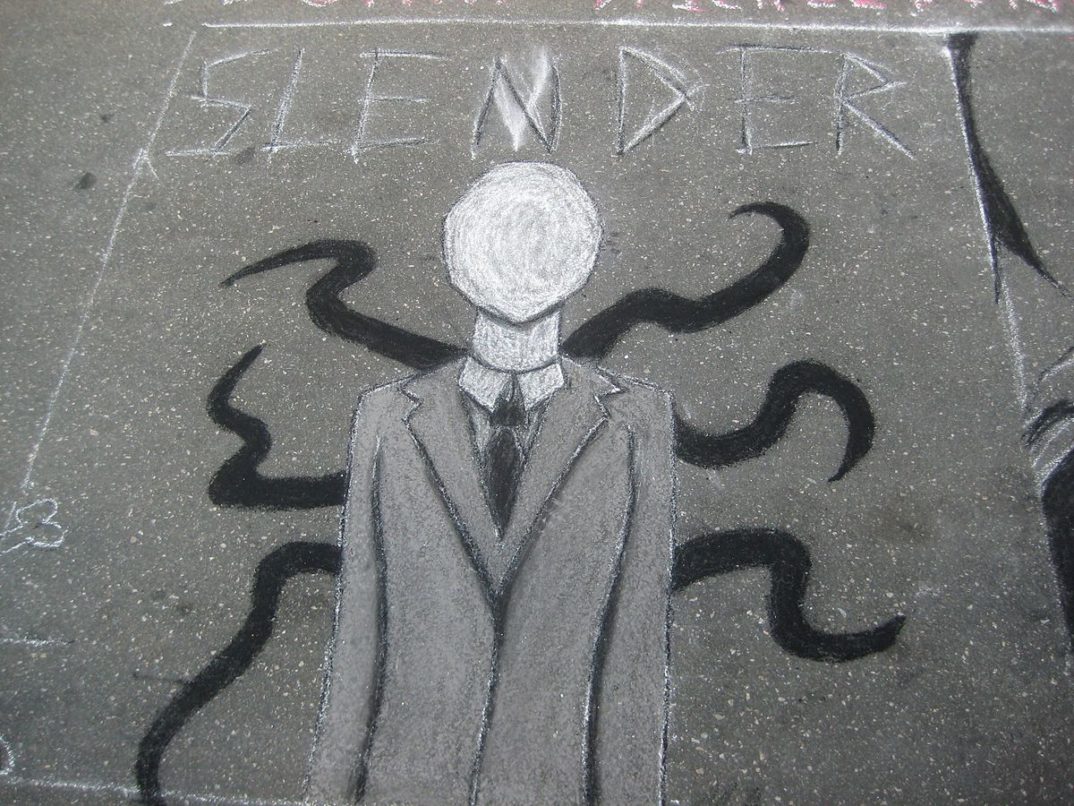

This case is noteworthy because of the youth of the victims and perpetrators and because of the savagery of the attack. The motive for the crime is also shocking. The two girls allegedly believed that they were being stalked by a malevolent entity named Slenderman. Slenderman is a fictional entity created for a Photoshop contest on a horror page on the Internet. He is an impossibly tall, thin man without a face who stalks children in the woods. The girls allegedly believed that Slenderman would kill them and their families if they did not sacrifice their friend to him. On September 13, 2017, one of the girls was found not guilty by reason of insanity. A doctor has diagnosed her with early onset schizophrenia. She will now spend three years in a mental institution.

The legal and moral issues central to this case are nuanced. Virtually every stage in the case involves important ethical questions. First, the case raises questions about the moral dimensions of children’s exposure to the Internet. The Internet has provided people with unprecedented access to information, but it can also be exceptionally dangerous. An obvious concern is that children will encounter dangerous strangers online. A less frequently acknowledged problem is that children are exposed to all of this information without any training on how to process and evaluate it. Despite its obvious importance, we don’t teach critical thinking classes at the elementary school level.

Students are exposed to massive amounts of information with very few tools to evaluate whether the claims being made are true or false. They are presented with photoshopped images that they aren’t aware have been altered. One might think that the obvious response to these concerns is for parents to simply monitor their child’s Internet use more carefully. It isn’t so simple; the problem has intensified. There was once a time when all parents had to worry about was monitoring Internet use on their desktop computer. Now, all sorts of portable electronic devices can easily access the Internet, and we simply can’t be with our children all of the time. It’s a problem with no obvious solution. It is important that people are able to express themselves freely, so, despite the dangers we can’t restrict content on the Internet (except under highly specified conditions).

Events that preceded the arrest also raise moral questions. Police were able to obtain a confession from one of the children. Her lawyer later filed a motion to exclude the confession, arguing that her young age and mental health issues made her incapable of understanding her right to remain silent. The judge disagreed. He said, “I’m satisfied that by a preponderance of the evidence, in reviewing the totality of the evidence that the Miranda rights were read to Miss Weier, that she understood them, that she gave them up-waived them, that he waiver was knowing, voluntary and intelligent.”

The girl’s confession was provided shortly after the crime. The confession was videotaped and has been made public. On the video, she clearly articulates her belief that the murder was necessary for the purpose of warding off Slenderman. There seems to be a tension here. In the final analysis, there are some inconsistencies in the judge’s rulings. The young woman, now 15, was found not guilty by reason of insanity. If her mental state rendered her unable to tell the difference between right and wrong at the time that the attempted murder was committed, what reason do we have to believe that she was competent enough to understand her rights at the time at which they were read to her?

It is unclear whether the second young defendant in this case will get a similar ruling. At the end of the day, the issue of whether the confession was admissible didn’t impact the case of the girl who was found not guilty by reason of insanity. She isn’t facing jail time. But if the conclusion is that the second girl was mentally fit at the time the crime was committed, the confession could impact her case substantially.

A third moral question concerns the fact that these children were tried as adults. When a child is tried as an adult, they often face much lengthier sentences should they be convicted. There are many conditions under which a child might be tried as an adult. The relevant concern involved here is the severity of the crimes. To many, attempted murder is a crime for which a person should receive a harsh sentence regardless of their age at the time that the crime was committed.

Others argue that when we treat children as adults because of the severity of the crime committed, we are letting our need for retribution get in the way of consistency in our judgments. If we treat children differently in other cases because they are unable to recognize the magnitude and consequences of their actions, murder or attempted murder is no different. The philosophy implicit in the juvenile system is very different—it is a system that prioritizes rehabilitation and behavior modification over concerns for retributivism. In other words, the juvenile system is more concerned with preparing young offenders to live healthy, productive, crime free lives. The adult system, by contrast, seems to be primarily concerned with ensuring that the offender “gets what they deserve.”