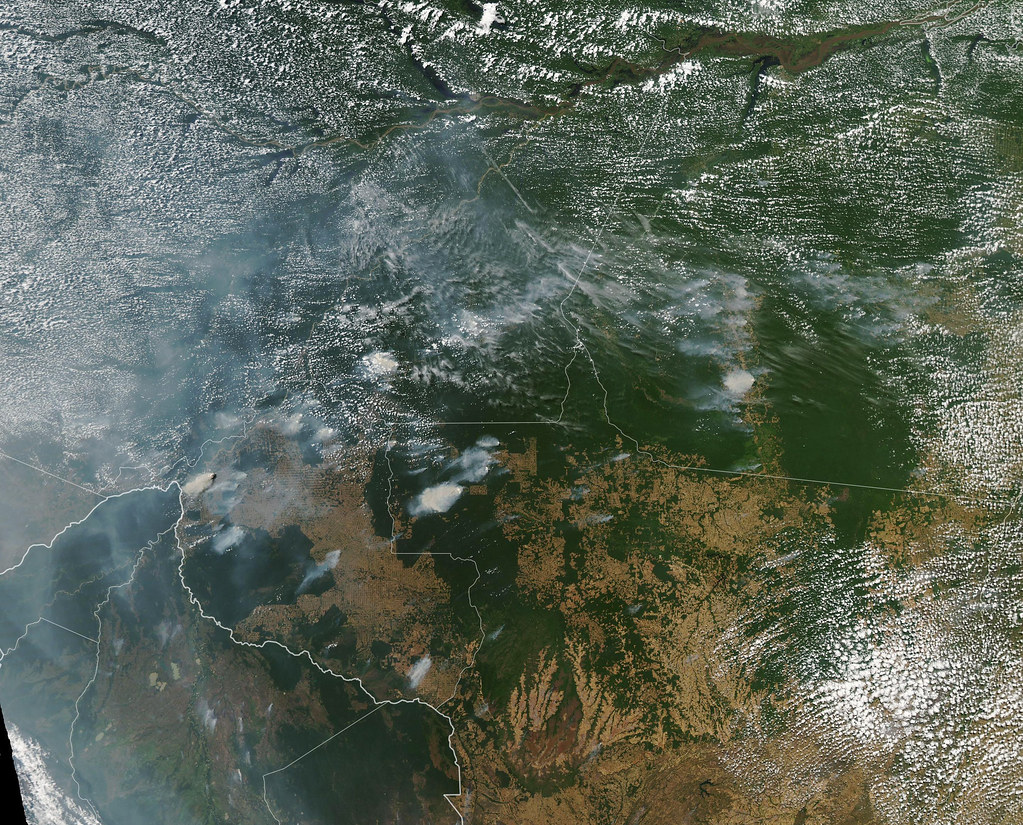

An eerie silence is descending across large swathes of the planet’s coral reefs. These once bustling and vibrant oceanic hubs are being transformed into bleak monotone ghost-towns by a process known as “bleaching.” Coral bleaching occurs when unusually warm ocean temperatures cause corals to expel the colorful algae that live symbiotically in their tissues, providing the coral with essential nutrients. We are currently in the midst of the fourth, and worst, recorded coral bleaching event. According to scientists at Coral Reef Watch, over 80% of the planet’s reefs have been impacted by bleaching since this event began in 2023, pushing reefs into “uncharted territories” and potentially past tipping points beyond which they will not be able to recover.

Coral reefs are essential parts of ocean ecosystems, with an estimated 25% of all marine species dependent on them at some point in their life cycle, despite them only covering less than 1% of the ocean floor. They are also essential to human life, with over 500 million people relying on them for food, and coastal communities depending on them for flood defense. The deterioration of these marine metropolises would be a catastrophe for both people and nature. The protection of coral reefs in the face of global warming is therefore a priority for marine conservation organizations.

All conservation organizations and reputable scientists agree that the reduction of carbon emissions through a socially just transition to clean energy is vital if we are to lessen global heating and prevent further damage to reefs. However, the speed and scale of the threat to coral reefs is leading conservationists to reach for faster and more direct techniques to protect them from rapidly rising ocean temperatures. It is against this backdrop that “synthetic biology” – biotechnology techniques to genetically engineer organisms, like gene editing – is being increasingly looked to as a solution. Conservationists hope to use the tools of synthetic biology to insert heat-tolerant genes into coral DNA to prevent them from bleaching when ocean temperatures rise. Such technologies have a history of sparking fierce public debate when used for agricultural purposes – think of the backlash against genetically modified food crops – but their use as a tool for conservation is still very much in the early experimental stages. Such use has therefore only recently become a matter for ethical consideration.

Proponents argue that humanity has a moral obligation to do our utmost to fix the damage humans ourselves have caused to ecosystems. Although this technology may be more intrusive than traditional conservation techniques, it essentially has the same aim of conserving species and restoring ecosystems. Those in favor can point to the fact that conservationists have already undertaken similar, albeit less technologically advanced, projects. Techniques such as selective breeding and artificial gene flow, where coral species that already possess heat tolerant traits are interbred and then introduced into struggling reefs, are already being used with some success. The use of synthetic biology is not far removed from this more traditional style of intervention it might be argued, and so there is no great ethical difference between these two approaches. If one is permissible, then so is the other.

Yet there remains a lingering feeling for many that such a radical intervention into the very essence of a coral organism – its DNA – is somehow different, and could in some significant way undermine the value that conservation seeks to preserve. Some may worry that it is one thing to assist the evolution of a coral population by introducing a naturally occurring but non-native coral species into that population; it is another to engineer entirely new artificial coral species and introduce them into a natural system. This level of intervention, it may be thought, erodes what is valuable about these systems in the first place – their naturalness. Coral reefs have developed autonomously through the co-evolution of huge numbers of different species over thousands of years. They are not the product of design but of spontaneous natural processes. Yet the use of synthetic biology would make them a product of design, specifically human design. If coral reefs can only exist because of human engineering, the line between them and an underwater aquarium wears thin.

Such feelings of unease might be given greater depth by considering the arguments of philosopher Eric Katz. Katz thinks that when conservationists intervene in a natural ecosystem to achieve some pre-established goal (like restoring the system or preserving biodiversity), they turn that ecosystem into an artifact. It ceases to be a natural ecosystem at all since it is now designed to fulfill a purpose given to it by human beings. For Katz, this means that the resulting ecosystem can only be “instrumentally” rather than “intrinsically” valuable. Instrumental value is the type of value something has in so far as it is good for achieving some other end. For example, a bicycle is valuable in so far as it is good for the purpose of cycling from one place to another. However, the bicycle is not valuable “in itself,” the bicycle does not have value beyond its function. It, like all artifacts according to Katz, does not have “intrinsic value.” Natural systems, on the other hand, Katz argues, have “intrinsic value” because they were not designed to serve any purpose, their value stems from their “autonomy” – from not being controlled and constrained by humanity. By imposing our purposes onto natural systems, the argument goes, conservation interventions erode nature’s intrinsic value, resulting in artifacts that have been manipulated to serve human desires and preferences.

Katz’s argument was initially constructed as an objection to conservation interventions generally, however, his argument is perhaps most forceful in cases like genetically engineered coral. The notion that the resulting engineered coral organisms are artifacts is hard to doubt. On Katz’s view, then, engineered organisms and the systems into which they are introduced lose their intrinsic value. They may still have instrumental value in so far as they fulfill human needs and preferences – for their ability to provide food, flood defense, tourism revenue, aesthetic pleasure and so on – but they are no longer valuable in themselves as natural systems.

Katz’s argument gives philosophical expression to a sense that there is more to nature’s value than the various benefits that humans get from it; that there is something deeply valuable about the spontaneous processes that led to the formation of ecosystems like coral reefs. However, many have pointed out that such arguments rely on an overly narrow understanding of nature in a world where humanity is increasingly and inseparably entangled with the natural world. In fact, many philosophers and conservationists have questioned whether any sense can be given to the distinction between humanity and nature in such a world. Bill McKibben argued that climate change has brought about “The End of Nature,” in the sense of a force that acts independently of humanity; while Steven Vogel has advocated for an “environmentalism after the end of nature,” arguing that “environmental questions are social and political ones, to be answered by us and not by nature.”

From this perspective, the idea that deploying synthetic biology converts reefs into artifacts is irrelevant, because the whole planet has already been transformed by human activity, and so is already, in some sense, an artifact. When the extent of humanity’s impact on the planet is properly understood, it becomes incredibly difficult to separate what is “natural” from what is “artifactual” and to make moral judgments based on this distinction. Is a coral reef that has been intentionally engineered by humans to become more heat-tolerant any less natural than one which has been bleached and decimated by human-caused global warming?

This is what Emma Marris has called “the paradox of pristine wilderness” – conserving ecosystems in their “pristine” historical condition increasingly requires intervention in and control of those ecosystems, so the more “pristine” an ecosystem looks the less truly “wild” it is likely to be. Some conservationists, like Marris, calling themselves “new conservationists,” have embraced this paradoxical situation, arguing that conservation must ditch old notions of nature and instead accept that we humans are now in the planetary driving seat. In the words of writer Stewart Brand: “We are as gods and might as well get good at it.” For these “new conservationists,” it is now up to us to decide the future of the planet and the tools of synthetic biology should be put to use as humanity sees fit.

While it is difficult to question the insight that humanity and nature have become so tightly interwoven as for it to be difficult to neatly separate the world into these two categories, that does not necessarily mean that there is no morally significant distinction to be made here. As technological progress continues to change the possibilities of human relations with ecosystems and the planet as a whole, we may question whether dispensing with the concept of nature is really appropriate. The use of synthetic biology for coral conservation represents the cutting edge of what will become a new horizon for the ability of human beings to control and manipulate natural processes. Although the use of these technologies may seem innocuous enough when it comes to preventing coral bleaching, humanity must consider how far we are willing to go down this path. To what extent should we go on engineering species and ecosystems so that they suit our own preferences? At what point would the planet’s once mysterious and unfathomable natural systems become merely a mirror of human values? With the prospect of even more intrusive interventions, such as the “white skies” of geo-engineering glimmering in the not so distant future, we must consider the extent to which it is morally permissible for human beings to manipulate planetary systems to suit our own interests.

Still, given the dire and rapidly worsening state of coral reefs, there may not be much more time for debate. Action must happen now, and those who argue against the radical solutions being offered by synthetic biology will have a heavy burden to bear if their arguments succeed in preventing such action, and, in doing so, contributing to the irreversible and devastating loss of the planet’s once magnificent coral reef ecosystems.