On September 26, President Trump announced he would be nominating Amy Coney Barrett to fill the Supreme Court seat recently vacated by the departed Justice Ruth Bade Ginsburg. This decision is not only controversial considering the fact that recent political precedent would imply that the winner of the upcoming election should choose the next Justice, but also because of the perception that Barrett is not only under qualified to sit on the Court, but also potentially unfit considering her strong religious views. Barrett is a stout Catholic, member of the spiritual group People of Praise, and has been vocal about the influence of faith on judicial ethos. Various politicians, activists, and even those with personal ties to Barrett have expressed staunch opposition to her nomination, most strongly on the basis of her perceived bias. However, in response to this criticism, many have come to her defense, arguing that not confirming Barrett on the basis of her religion is in fact religious discrimination.

Are these critics right to assert Barrett’s religious views are a conflict of interest? Are her defenders right to argue religious discrimination? And which is the correct interpretation of the First Amendment: secularism or religious freedom?

Secularism is informed by secular ethics, which derives morality from the human experience and rationale, rather than perceived higher powers or specific religious text or tradition. Secular states are countries guided by secular values in the political and governance process, neither favoring nor discriminating against any specific religion. The majority of countries in the world are considered secular states, including the United States.

The majority of the arguments over Barrett concern different interpretations of the principle of secularism. The principle of secularism aims to separate the state from any religious guidance or influence. In the United States, this concept is often boiled down to the “religious freedom” communicated in the First Amendment of the United States Constitution. Republicans, and others defending Barrett argue that to use her faith, or its influence on her, as a ground for not approving her is in itself religious discrimination. Critics, though not Senate Democrats specifically, are wary of Barrett because of their concern that her entire judicial philosophy is anti-secular if it is influenced by her faith.

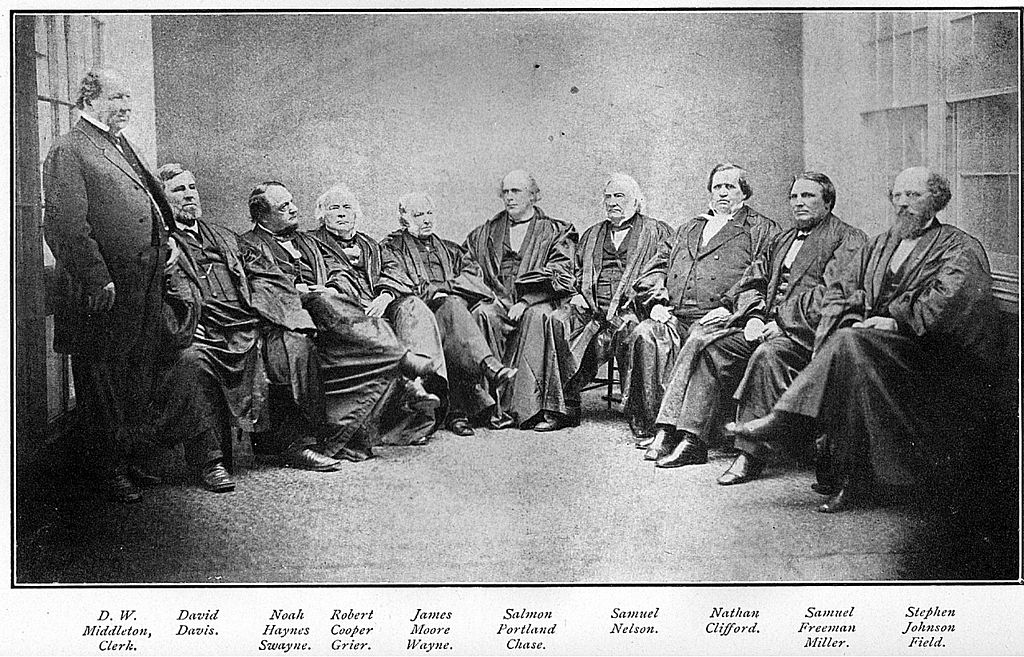

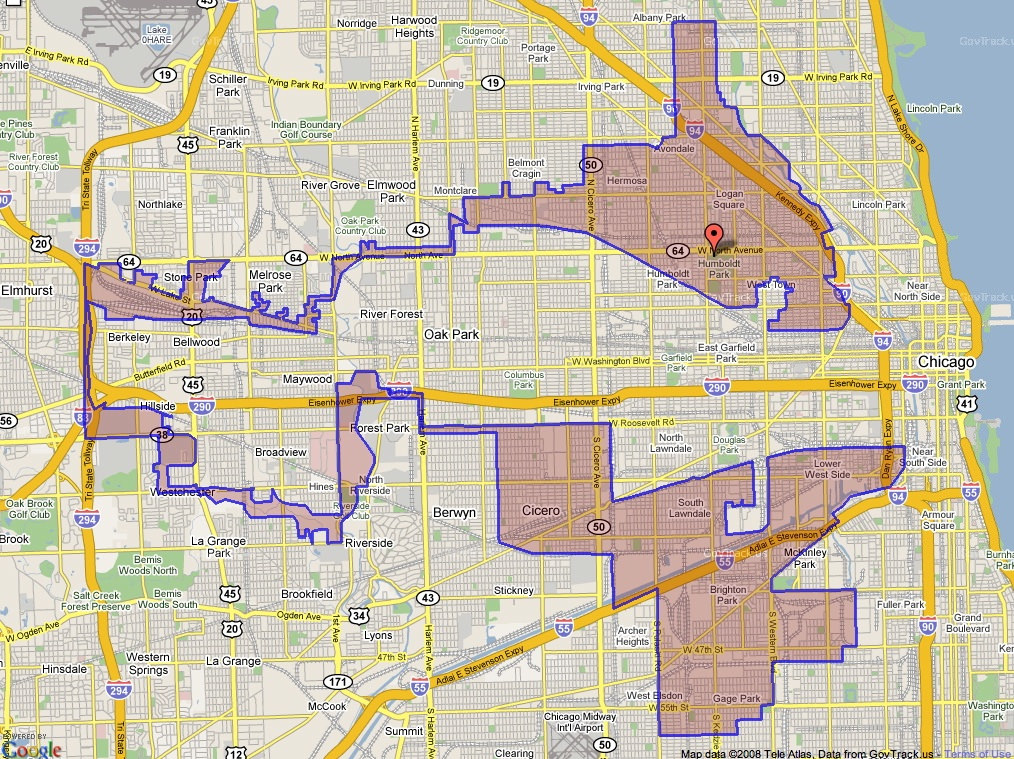

This is not the first time that Barrett’s religious views have been brought up in the context of her judicial discretion. In 2017, Barrett was nominated for a federal judicial appointment by President Trump. During her confirmation hearing, Democratic Senator Barbara Feinstein expressed the concern that “The dogma lives loudly” within Barrett. Feinstein’s comment was simultaneously blasted as an expression of religious discrimination and rebranded by Catholics across the internet proudly. After Barrett’s nomination, this interaction has been visited again by Democrats and Republicans alike, by the former to reassert concern for her religious bias and by the latter to imply that much of the criticism of Barrett results from religious intolerance. Both of these concerns can be backed up by evidence. On the one hand, the current Supreme Court hosts 5 Catholics, by far more than any other religion. Despite this newfound domination of the bench, historically only 13 Catholics have ever sat on the Supreme Court, despite making up roughly 20% of the United States population. Some, such as law professor Cathleen Kaveny argue that the recent appointment of so many Catholics to the Supreme Court is a “victory over historic prejudice.” While Catholics do not face much modern day social persecution in the United States, that has not always been the case. Between the late 19th century and early 20th century, Catholicism in America was associated mainly with immigrants from Northern and Eastern Europe. These groups were discriminated against not only due to their immigrant and ethnic status, but also on the basis that Catholicism was morally perverse. Historically, Catholics were one of the groups targeted by the Ku Klux Klan, though this is not necessarily the case in modern times.

On the other hand, a Supreme Court made up of staunchly religious Justices, or too many from a certain religious faith, arguably stands in direct opposition to the principle of secularism. This guiding principle, most commonly associated with the separation of church and state, has been highly regarded since the formation of the United States. While the separation of church and state is often brought up in reference to legislative attempts to favor or discriminate on the basis of religion, the Supreme Court’s role in consistent affirmation of secularism is paramount to its existence. The Court regularly makes judicial decisions which involve the First Amendment, for example, recently in American Legion et al. v. American Humanist Assn. et al. Having a court made up with even a few deeply religious justices could impact the judicial philosophy of the most powerful court in this country. This alone a cause for concern considering the fact that certain religious traditions take hard, and sometimes unpopular stances on highly debatable moral issues. This is especially true of the religious group that Barrett identifies with, the People of Praise, which has been criticized for its reinforcement of gender roles and female subordination.

Outside of her possible beliefs, Barrett has been vocal about how her faith guides her stance on abortion, despite the fact that the majority of Americans support a woman’s right to choose. While the popularity of a certain legal stance does not necessarily speak to its morality, there is certainly an ethical value in having a judicial system which is fairly representative of the moral inclinations of the majority of the population. While the Supreme Court is not meant to be a political or moral institution, there are certainly righteous ethical concerns about our Justices sitting on the extreme end of the moral spectrum and serving to guide the legal interpretation and judicial discretion in every courtroom in America.

Barrett’s faith is not the only aspect about her which could guide one’s moral stance on her fitness to serve on the Supreme Court. Her age, gender, and even personal life might also be taken into account when deciding how one feels about her nomination. However, as long as discussions about her faith dominate political and media debate, our moral inclinations about her religious views will likely guide whether or not we believe she should be confirmed.