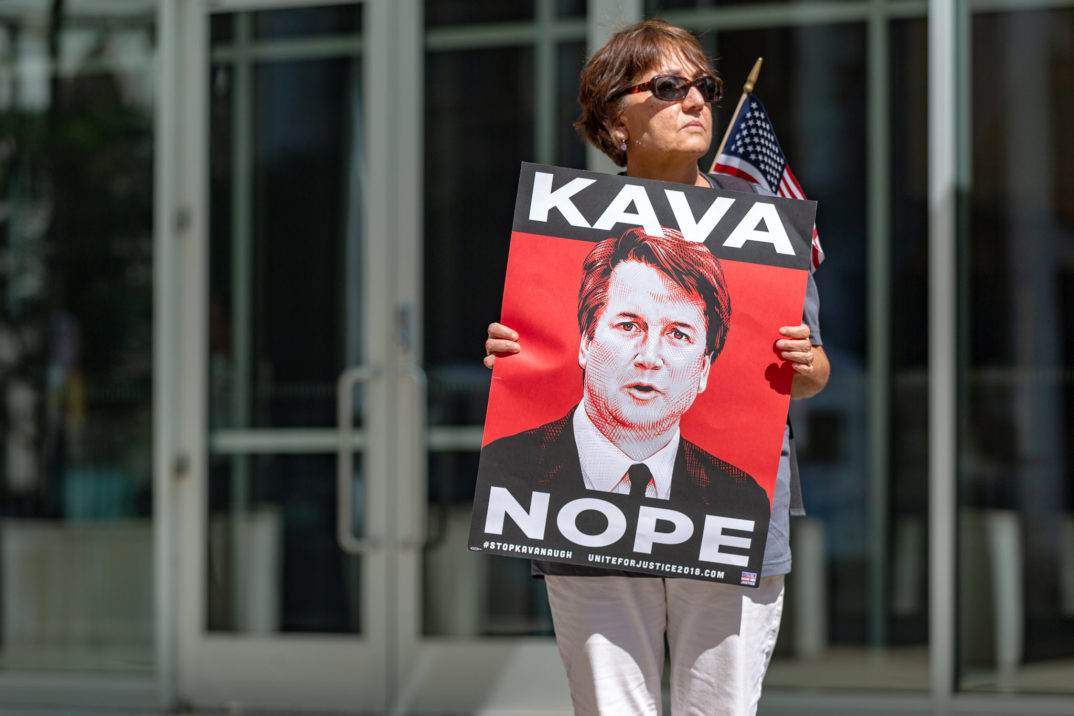

How Should We Consider Brett Kavanaugh’s Sexual Assault Allegation?

For several weeks, coverage of the already-controversial proceedings surrounding the confirmation of Supreme Court nominee Brett Kavanaugh has been dominated by the possibility of sexual misconduct on the part of the nominee. Prior to Christine Blasey Ford’s sexual assault allegation, Kavanaugh was already regarded by many to pose a threat to women’s rights. Those voices have now redoubled, resulting in the nomination committee delaying a vote on Kavanaugh’s confirmation until after Ford has testified before the committee. Kavanaugh has denied the allegation.

Given a standoff between two conflicting individual claims—and, as of yet, no formally presented evidence—there is no point to arguing about the validity of Ford’s allegation. Nor would it be fruitful to delve into anecdotes reflecting each party’s character: such a discussion may be interesting, but ultimately comes down to hearsay. Instead, let us take this moment to consider the full ramifications of Ford’s allegation. How should the nomination committee proceed to maintain its ethical integrity?

It seems clear that the decision to delay a scheduled vote in light of the allegation was a sound one. An appointment to the Supreme Court is a decision that will affect politics, policy, and therefore the lives of millions of Americans for years if not decades to come. Unlike the winners of elections, members of the Supreme Court are appointed for life; they will not be removed from their position except in the most extreme cases, let alone in the next election cycle. This suggests that any decision made by the Senate in this situation should be a deliberate rather than a hasty one. It is true that the United States government does eventually need a full Supreme Court to be operating as was intended, so there is a good reason to avoid indefinite delay, but the Court has managed for more than a year with only eight justices, and the court’s role in the government is rarely especially time sensitive—there is no reason to begrudge the committee another few weeks or even months in order to be sure of the correct decision.

When the committee has heard Ford’s testimony, allowed Kavanaugh to respond, and examined the available evidence, what should its reaction be? Perhaps more importantly, what should our reaction be? What are the circumstances that would justify denying Kavanaugh’s confirmation? The most extreme case would be if Kavanaugh were convicted of sexual assault. In that situation, most people would agree that appointing him to the court would be unethical. But it is worth investigating exactly why one would hold this view. Is it a problem to have committed any crime? Some would say yes, especially considering the Supreme Court’s role in interpreting laws for the national legal system. But should that include all crimes, including traffic violations? Most people would not hold themselves to the same standard. A compromise might be to take only felonies or violent crimes under consideration. And would this edict have a statute of limitations? The allegation against Kavanaugh is from when he and Ford were both in high school; can we entertain the possibility of dramatic changes in personality over the span of several decades? Then again, the case is mounting in favor of a pattern of unacceptable behavior on the part of Kavanaugh: a second allegation has been brought to bear, this time from Kavanaugh’s Yale classmate Deborah Ramirez.

Furthermore, should all public officials be held to the same standard? Is it only because Kavanaugh’s potential position involves the administration of law, or is it a matter of putting any kind of criminal in any position of power? The answer to this question would have major implications outside of this case, as allegations of misconduct are brought up in elections around the nation.

Another way of looking at this problem is to ask what is achieved by keeping someone off the bench because of a past crime. There are two distinct possibilities: either the crime compromises the ability of the perpetrator to carry out the duties associated with their position, or the denial of the Supreme Court seat is an extension of the punishment for the perpetrator’s crime. The goal is either to protect the American people from a dangerous agent, or to mete out retribution for a crime.

This conclusion informs our decision about less extreme hypotheticals around Kavanaugh’s case. He has not been convicted of a crime, and the assault alleged by Ford would have taken place when Kavanaugh was a minor, meaning that even if he had been convicted at the time, there would be no continued legal consequences in force today. If keeping Kavanaugh off the Supreme Court were only a form of retributive justice, it would be a difficult argument to support. However, if the aim is to judge Kavanaugh’s overall fitness for the court, taking Ford’s allegation under consideration might be prudent. While it could be argued that Ford’s testimony is very convenient to a perceived liberal political agenda, this fact alone should not be enough to disregard her testimony altogether. Her speaking out is no more politically expedient to the left than her silence would have been to the right. In a case outside of the political sphere, we would not assume ulterior motivation from an alleged victim of sexual assault.