The trend of American secularization continues. A recent report by the Pew Research Committee notes the accelerating number of “nones” – those without formal religious affiliation – in the U.S., and finds that under several different scenarios America will be a Christian minority nation by 2070. The report estimates that as of 2020 approximately 64% of Americans identified as Christian. While explanations for the shift away from Christianity are multiple and complicated, it echoes patterns of secularization in Europe.

There are reasons to be wary of overinterpretation, as a lack of affiliation of formal religion does not mean that someone is not informally religious, spiritual, or otherwise wedded to a guiding belief system. Similarly, Christianity is no monolith and encompasses a wide array of sects with varying religious commitments (and varying levels of commitment to those commitments). But, big picture, the church as an institution is in demographic decline.

Religious practices organize people socially and culturally, not just theologically. And whatever its democratic woes, Christianity continues to have a powerful role in American politics, as reflected by recent Supreme Court decisions on abortion and school prayer.

Of particular philosophical interest, religion provides a (plausibly) objective basis to morality and many believers worry about the metaphysical foundations of ethics absent something like a god.

Put differently, what underpins morality in an irreligious society? And relatedly, what is the worry of having a moral system without foundations?

Questions of morality are familiar. Is killing wrong? What about in self-defense? Is it okay to break a promise? To tell a white lie? To collect and sell data from the users of an app? However, there are also questions we can have about morality itself. This is the domain of metaethics. One of the most prominent debates within metaethics concerns the objectivity and reality of ethical claims.

Consider a claim like: “murder is wrong.” A natural interpretation is that this statement is making a factual claim about the moral wrongness of murder, and the claim is either true or false. (This is the claim of moral realists. Though in another tradition in metaethics, called noncognitivism, ethical claims are not treated as being true or false at all.) Assuming the ethical claim is true (or false), the next issue is explaining what makes it that way.

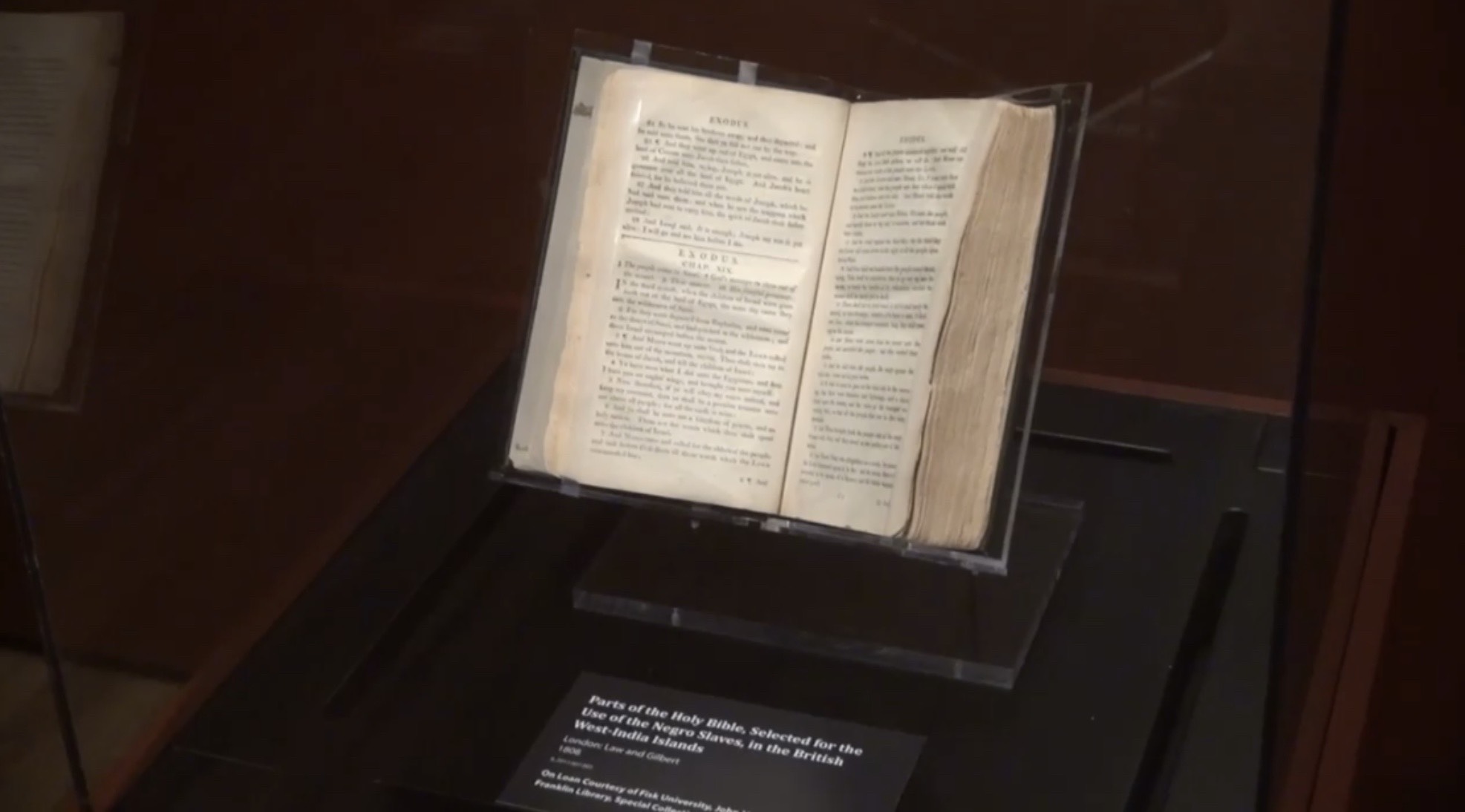

One answer is that something in the world makes the ethical claim true. For a religious or spiritual person, this something is often that a god commands it.

But even within religious thought, such a move is not without difficulties. Plato’s famous Euthyphro dilemma asks whether something is good because it is beloved by the gods, or beloved by the gods because it is good. Nonetheless, religious traditions have additional resources to draw upon when it comes to the truth of ethical claims.

Absent religion, things get trickier. The Australian ethicist J.L. Mackie influentially argued that if morality is something in the world, it is an awfully strange thing. We know of no bits or bobs of the world that seem to constitute moral wrongness, we don’t know how to measure “ethicalness” or move it around, and there seems to be nothing physically different between lying to the police about what’s in your basement to save a refugee’s life or to save your heroin operation. What’s more, we might question what morality really explains. If asked to account for the actions of Adolf Hitler, one can appeal to his psychology, his politics, and the historical context. It is not obvious what additional information is provided by asserting that Hitler is also “evil.” This line has been argued most prominently by the philosopher Gilbert Harman.

Broadly speaking, an account of morality that places moral facts – the wrongness of eating meat, for example – out in the world appears somewhat out of step with our best current scientific accounts.

Evolution makes this concern more acute. Philosophers Sharon Street and Richard Joyce have both argued that evolutionary theory “debunks” morality, where debunking arguments are a specific kind of objection which attempt to show that the causal origin of something undermines its justifications. In particular, evolution is responsive to fitness, not responsive to truth, so the concern is that there is no reason to expect from our evolutionary history that we would have evolved with even an approximately correct set of moral beliefs. The idea is we evolved our general moral commitments because cooperative humans that did not kill and steal from each other constantly were reproductively successful, not because they were perceiving the moral structure of the universe.

This argument is especially powerful because it undermines the evidence on which one would build a case for the metaphysical foundations of ethics. Our everyday moral talk often treats morality as if it is true – we refer to murder as wrong and helping the needy as good. Ethicists take this seriously as (at least initial) evidence for the objective reality of morality, absent compelling reasons to think otherwise. However, if our moral intuitions can be effectively explained by evolution, then the evidentiary basis on which moral realism derives its plausibility evaporates.

These arguments have not gone unaddressed and the debate continues. For example, we presumably did not evolve to learn particle physics, and yet no one considers it “debunked” by evolution.

Other philosophers take completely different approaches. Immanuel Kant famously argued that our morality is rooted in our nature as rational beings that can act in accordance with reason. His work suggests that the truth of moral claims is not written in the stars. Instead, as free-willed rational creatures, it is our duty to recognize the force of moral law. The appeal of approaches like Kant’s is that there can be objective answers to moral questions, even if the foundation of morality lies in our own nature rather than some thing out in the world.

Still, we might ask why all these questions of moral foundations matter at all, and whether religion actually solves the problem. For those concerned by Christianity’s decline, the ultimate fear is likely an amoral world where nothing is right or wrong. Let us grant for the moment that if god/gods exist, then murder is really wrong (here using the time-honored philosophical practice of strategically italicizing words). It is not a glorified opinion. It is not wrong on the basis of reasons or political commitments. It is not only wrong for a given person, or a given society. It is not wrong because we are a specific species with a specific evolutionary history of cooperation that has given us a hard to shake set of psychological intuitions about morality. It is really, truly, against-the-divine-structure-of-the-universe Wrong.

Note that this moral fact does not depend on whether people are religious. It instead depends on the truth of some religious tenets. The popularity of religion is simply unrelated to questions of the existence of moral foundations.

Alternatively, our overriding concern might not be a philosophical one related to whether or not there is an objective basis to morality, but a social one regarding people’s belief in moral foundations. If no one believes that anything is really wrong, so the worry goes, then what is to stop absolute hooliganism? We need the belief in moral foundations for their salutary effect on behavior. This, however, is ultimately a scientific question about, first, whether the religiously unaffiliated are less likely to believe in objective morality, and second, if those who do not believe in objective morality behave less ethically (by conventional standards).

Some research suggests that religious people and secular people have slightly different ethical commitments and behaviors, but there is no evidence of general amorality. If anything, the rise of the “nones” spurs objections to some religiously motivated practices – like abortion bans – on explicitly ethical grounds. Changes in America’s religious landscape will result in changes in its moral landscape, but this does not entail Americans being generally less concerned with morality. And while philosophers and others may be fascinated by the (possible) foundations of morality as an intellectual project, it remains to be seen whether this project is genuinely socially motivated. We simply are, descriptively, organisms that care about ethics. Most of us anyway.