On March 10th, Facebook modified its free speech policy to allow for some calls to violence directed against Russian President Vladimir Putin.

More strikingly, a week earlier, Senator Lindsey Graham explicitly called for the assassination of President Putin.

Is there a Brutus in Russia? Is there a more successful Colonel Stauffenberg in the Russian military?

The only way this ends is for somebody in Russia to take this guy out.

You would be doing your country – and the world – a great service.

— Lindsey Graham (@LindseyGrahamSC) March 4, 2022

Politically, it is ill-advised to blithely call for an assassination in the middle of a tense diplomatic situation, and Senator Graham’s actions were criticized by politicians on both sides of the aisle.

And yet one cannot help but feel the emotional impact of a Clint Eastwood-esque narrative in which all one has to do is kill some bad guy and geopolitical problems go away. Senator Graham called on the Russian people rather than the CIA, but it nonetheless raises the unsettling question: is there a (moral) place for assassination in international politics?

The question is not as far from contemporary practice as it seems. Democratic nations like Israel have utilized political assassination. Ostensibly the United States has formally banned political assassination since the signing of Executive Order 11905 in 1976, yet it makes frequent use of “targeted killing” in its international policy, usually of actors designated as terrorists, but also of Iranian General Soleimani. The straightforward reply is that these actions are unethical, but the morality of assassination is not as straightforward as one would hope and is deeply revealing about international ethics.

The intuitive ethical appeal of killing political leadership is that the harm is, in theory, localized. It has not gone unnoticed that those who declare war rarely fight in them, and the harms of war (like the harms of sanctions), tend to refract over the most vulnerable members of society. Assassinations, by contrast, suggest the possibility of getting at those responsible and few others. Defenders of ethical assassination – like political philosophers Andrew Altman and Christopher Wellman and Eamon Aloyo and military strategist Lieutenant Colonel Ralph Peters – invariably allude to the possibility of lesser and more targeted harms.

In their discussion of political assassination, Altman and Wellman, write “once one agrees that armed intervention is sometimes admissible, it becomes very difficult to argue consistently that assassination is always morally impermissible.” The idea here is a parity of reasoning argument. If we think a political leader is so reprehensible as to justify the brutality of armed intervention, then why not assassination? Is assassination somehow morally worse than war? For that matter, is assassination worse than oppressive sanctions?

When pushed for reasons, it becomes difficult to draw these boundaries in a principled way.

Before embarking on this discussion, it needs to be emphasized that the argument that claims “IF armed intervention is justified, THEN so is assassination” must clear an exceedingly high bar. It is perfectly legitimate to question whether armed interventions are ever ethical, especially unilateral interventions. In their account, Altman and Wellman stress that such decisions would need to be made by the international community rather than single actors, and still they worry, rightly, whether such decisions would be subject to abuse. As in the case of the assassination of General Suleimani by the United States, it is all too easy to imagine international assassinations as a mere cynical extension of national interest. Hypothetically, assassination could be justified even in cases where armed interventions are not justified, but that would require different and stronger arguments than parity of reason.

The question that follows then is: Is there anything specifically morally abhorrent about assassination that does not apply to armed intervention more generally?

One strategy to clarify the specific problem with assassination is by appeal to international law. The landmark international treaty on the rules of war, the Hague convention of 1899, declared it “especially prohibited” to “kill or wound treacherously individuals belonging to the hostile nation or army.” This sentiment against assassination has been reflected in later law like the Geneva Convention treaty of 1977. These laws concern assassination in war, but presumably assassination would not be outlawed during war time but permissible during peace time. The limitation of this response is that it grounds an ostensible ethical difference in a merely legal one, which can be changed with the stroke of a pen.

A slightly different spin is that a prohibition on assassination is needed to constitute effective international government and law in the first place – that absent this basic decency any international order becomes a nihilistic race to the bottom. As the blowback to Senator Graham’s comments shows, even talk of assassination is corrosive to serious international politics. This line of argument is more compelling, but for full strength it assumes that potential targets are (at least partially) participating in international governance, which may not always be the case. Presumably an international order would not be threatened by actions directed at those fully outside it, as long as there was internal agreement.

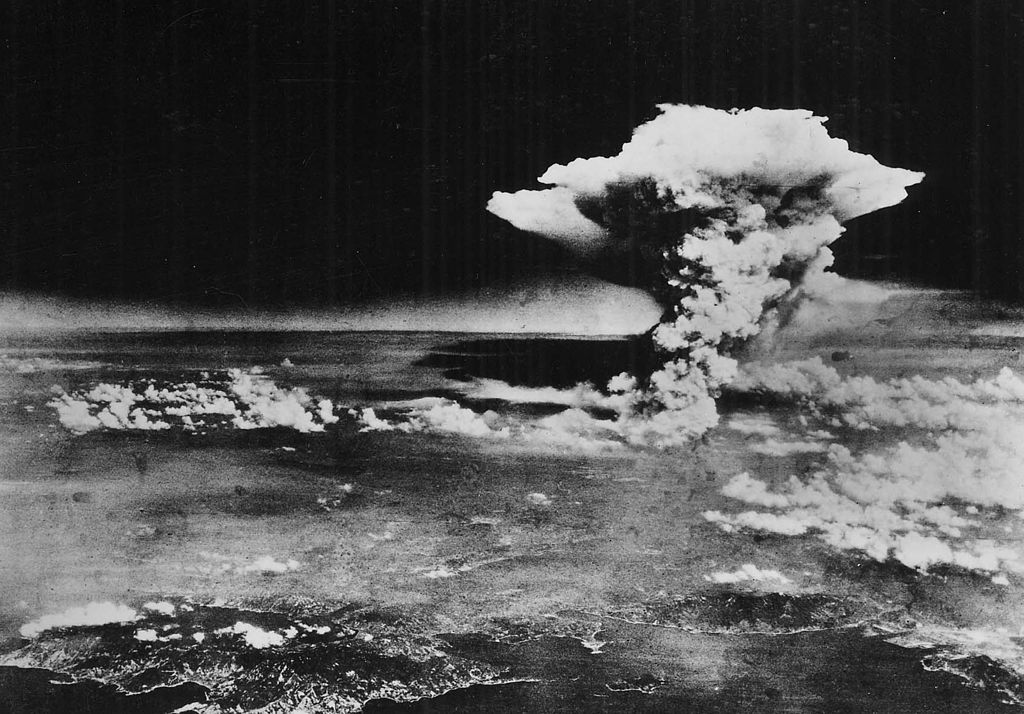

A second category of response is that assassination is wrong because it is the ethically wrong way to do war. The military ethics tradition of just war theory (if taken as more than an oxymoron) concerns itself with both justice in the declaration of war and right conduct in war. Right conduct is classically characterized by not targeting, and minimizing collateral damage to, civilians. This concern is reflected in prohibitions for weapons incredible in their destructive scope, like chemical or biological agents, and/or indiscriminate in their targeting, like anti-personnel landmines. However, the intuitive argument for assassination is precisely that it (in theory) minimizes collateral damage and civilian casualties, so by the standards of just war theory assassination appears more moral.

An alternative focus is the “treachery” alluded to in the Hague Convention. Modern understandings and law regarding just war are rooted in older discussions of chivalry and honor. From this perspective, the differentiating wrongness of assassination is that it is uniquely treacherous and dishonorable. Assassinations often involve subterfuge and target someone other than a soldier on a battlefield. However, the same concerns would apply to other common military tactics such as drone strikes and night raids. Moreover, if the assumption about the more limited harms of assassination is correct, forbidding assassination on the grounds of its treacherousness places the “honor” of leadership above the lives of soldiers and civilians.

The final way to characterize the wrongness of assassination is not by appeal to principle, but to challenge its claims to minimizing harms. High-profile political killings are as often the start of atrocities as the end of them, igniting retaliatory violence or wars for succession. In one of the most extensive historical investigations of political assassination to date, historian Franklin Ford concluded “[political assassination’s] demonstrable tendency has nearly always been to besmirch the perpetrator’s credentials, while undermining his chances of any lasting political success.” Similarly, another evidence-based analysis found high levels of instability and violence after successful assassination for governments without well-ordered succession – and assassinations of course do not always succeed, with failed assassination coming with their own consequences.

Even in cases of stable succession there is still no guarantee that the assassination will lead to positive change. This is the problem with the “bad guy” narrative. No matter how morally reprehensible, political leaders do not simply carry their country’s domestic and international problems around with them, to be neatly cleaned up after they fall. By focusing on singular villains we can neglect to appreciate the context behind political actions and the larger structures that maintain and exert political power. Nonetheless, especially in more dictatorial regimes, political leaders do have decision-making powers. The challenge however is to get political decision-makers to decide differently, not simply to eliminate them and let politics play out as it may.

Assassination then appears at the very least no more ethical than armed intervention, and because of its deleterious effects on international legitimacy, likely worse. It is not good ethics and it is not good politics. Nonetheless, advocates of assassination are right that there is something monstrous in the way conflicts between governments are settled via the lives of their people. As Lieutenant Colonel Peterson put it, “national behavior [of states] reminds me of those feudal squabbles in which minor nobles dueled by killing and raping each other’s serfs and burning offending villages.” Assassination, although itself impermissible, suggests an alternative vision for international ethics – thinking small. In a world of sanctions and cyberattacks, why can we not tailor these to target leadership and other influential actors more specifically? Russia is a test case, with sanctions starting to directly target oligarchs and legislators. However, not just in Russia, but everywhere, how would political decisions or actions change if every politician needed to worry about being embroiled in the conflicts they helped to create?