The Hiroshima Bombing: Was it Terrorism?

Terrorism is a word often associated with its modern context. When we think of terrorists, we think of masked gunmen attacking shopping malls and beaches, or planes flying into the World Trade Center on September 11th. Rarely do we consider events that predate the 21th century – events that may have taken place before the modern notion of terrorism arose, but that also relied heavily on the killing of civilians and fear to accomplish their aims.

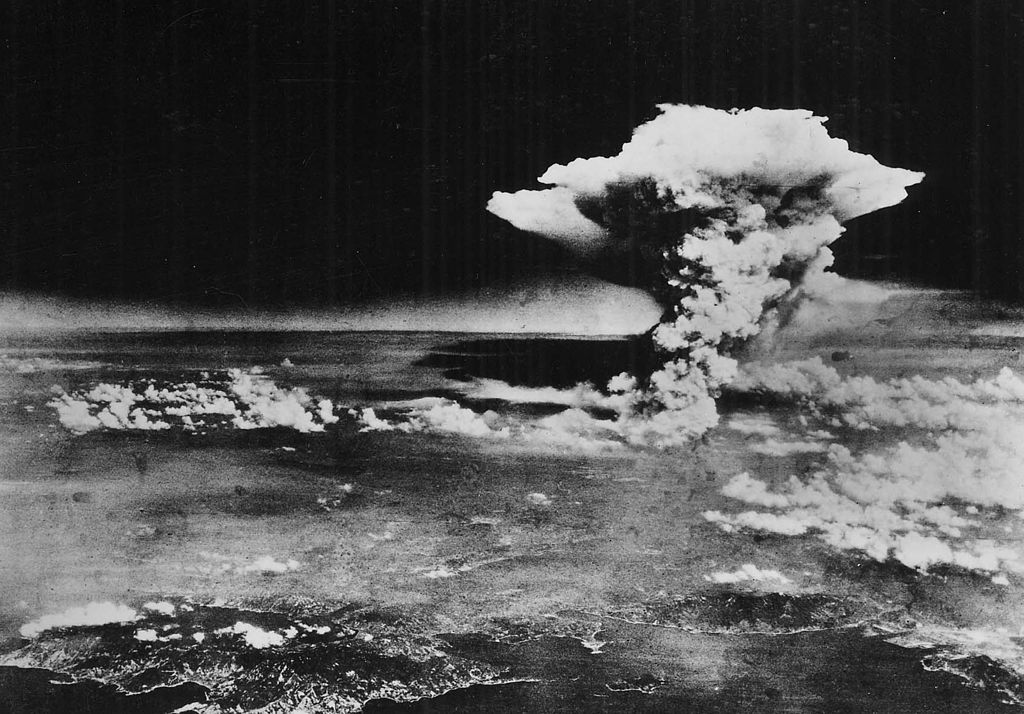

Such considerations are no more important than now, as the world commemorates the 70th anniversary of the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Seventy years later, debates about the ethics of the bombing continue to play out. Among arguments about the bomb’s justification, though, lie motives that, if the bombings were carried out today, would strike many as terrorism. In this regard, should the Hiroshima and Nagasaki bombings be considered terrorist acts?

It may, according to some, depend on who is committing the act. The United States is a state actor, a distinction that sets it apart from non-state groups like the Islamic State. By some definitions, this distinction matters; an act of terrorism can only be committed by a non-state actor, according to the State Department’s definition. Yet others, such as the FBI, do not make such a distinction, instead focusing on the intents, rather than the identities, of the perpetrators.

It is also worth noting how often terrorism is used to “other” certain acts. More often than not, especially in the domestic context, “terrorism” is used to describe violent acts perpetrated by Muslims or non-white Americans. The same could be said internationally; some have argued that US drone strikes could be classified as terrorism, a classification usually used to refer to attacks by Al Qaeda or the Islamic State. It is difficult to apply the designation of terrorism to ourselves, the temptation to designate others with it all too easy. Quite possibly, then, a designation of terrorism may depend on who is creating the designation.

Considerations of the atomic bombings’ legacy may also depend on the idealized lens of history. The atomic bombs, we have been told, were necessary to end the war in Japan. They saved more lives than they took, it has been said, removing the need for a costly ground invasion. Despite facts that contradict it (estimates at the time approximated casualties of around 40,000 Americans in the event of a ground invasion), this narrative is persistent, casting the bombings in the light of moral conquest. Even though some now argue that Japan would have surrendered without use of the bomb, it is still seen as a necessary – and even lifesaving – measure. This perspective is hard to shake, yet looking beyond its influence is necessary to gauge just what the intent behind the atomic bombings was.

After stripping away how it has been memorialized, such intents seem in line with a designation of terrorism. As chronicled by The Atlantic’s Paul Ham, these motives cast the bombings in a less idealistic light. Foremost among them? “The target should: possess sentimental value to the Japanese so its destruction would “adversely affect” the will of the people to continue the war…” Central here is the use of “the people.” While the ultimate goal was to lead the Japanese government to capitulate, the atomic bombings pursued that goal through the mass killing of hundreds of thousands of civilians – “the people” in question. According to Ham, this motive was a prime consideration in many deliberations about the bomb. Kyoto, originally the prime target for the bomb, was initially considered partially due to its rich cultural and historical value – value that would make its fiery destruction even more impactful on Japanese morale.

Additionally, while officials ultimately tried to cast Hiroshima as a military target, The Nation’s Christian Appy points out that “if Hiroshima was a “military base,” then so was Seattle; that the vast majority of its residents were civilians; and that perhaps 100,000 of them had already been killed.” While it was equipped with some military infrastructure, targeting the center of the city ensured that destroying it alone was hardly the goal. Targeting a major city was also designed to spread fear of the weapon beyond Japan’s borders; as The Nation’s Gar Alperovitz points out, “impressing” Russia with overwhelming military might was a key goal of the bombings.

In this regard, classifying the Hiroshima and Nagasaki bombings as solely military means to end the war seems inaccurate. While wholesale destruction was one goal of the bomb, its ultimate use was to crush America’s enemies and impress its rivals, with fear as its primary instrument. To do so, vulnerable civilian populations were overwhelmingly targeted and chosen to bear the brunt of the horrific violence – both at Hiroshima and, a few days later, at Nagasaki. It appears, then, that the atomic bombings could fall within the lines of being considered a terrorist act.

Regardless of whether it fits the exact definition of terrorism, though, the darker legacy of the Hiroshima and Nagasaki bombings must be remembered. It was a legacy that ended a long line of atrocity, one that saw tens of millions die during the Second World War. But it is also a legacy that led to the deaths of hundreds of thousands of civilians at Hiroshima and Nagasaki, at a time when such costs may not have been militarily necessary. As Americans, it is difficult to imagine this cost, and, given the fact that our leaders have not yet formally apologized for the bombings, a full reckoning of its effects has not yet been realized. As the years go by, and the survivors of the bombings grow fewer and fewer, grappling with the legacy of the destruction we unleashed is one of our greatest responsibilities.