Ever since the decision in Dobbs was handed down, there’s been a great deal of ink spilled about the Supreme Court “going rogue.” Whatever image those words are meant to conjure, it can’t be that simply by contradicting popular opinion justices act wrongly. Indeed, to do its job and fulfill its essential function – safeguarding individual rights and acting as legal backstop and ultimate umpire for conflicting claims to basic protection – the High Court must be able to act in opposition to the majority’s will. We should all be relieved that when it comes to who receives a fair trial or who may cast a ballot, we don’t simply put the matter to a vote (or do we?).

We think that the fundamental liberties that citizens enjoy are not the kind of things that should expand and contract with the ebb and flow of favorable representation in Congress.

As Evan Arnet argued yesterday, sometimes the sausage that our legislature – held hostage by party politics – produces simply won’t do. Everything can’t depend on a mere up or down vote; some things must be guaranteed. Enter: The Supreme Court.

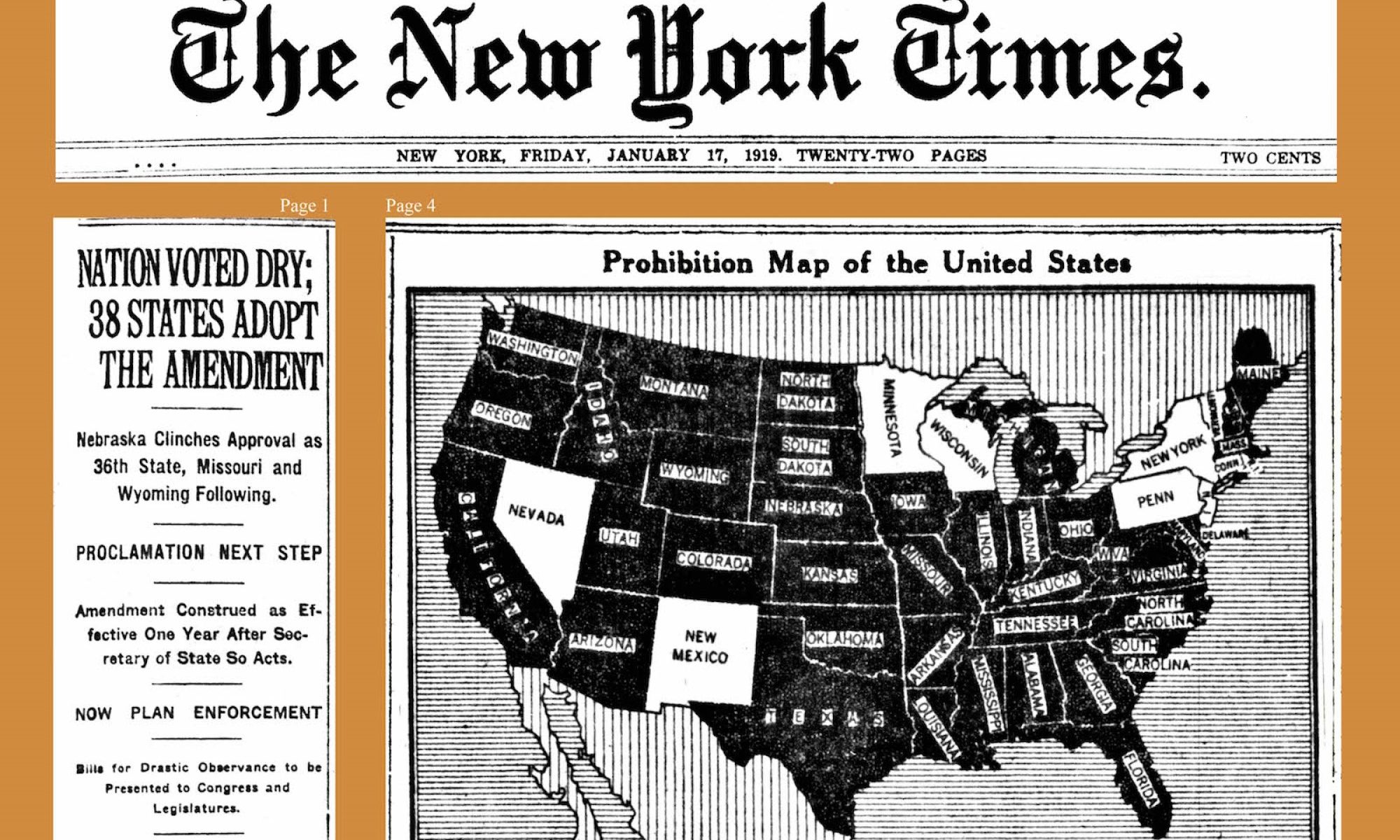

In no small part, our need for the High Court to chaperone the legislature stems from the fact that the masses are deeply misguided when it comes to the facts on the ground (see The New York Times’s recent moderated discussion with pro-life and pro-choice focus groups where multiple respondents on both sides thought that abortion was more physically dangerous than childbirth for a woman and estimated that 30-40% of abortions take place after the first trimester – when in reality it’s less than 10%). What we require is a final ruling made by legal experts standing above the political fray who see the matter clearly and can anticipate the legal implications that we mere mortals hardly perceive.

So rather than the common complaint about the justices being out of step with the court of public opinion, the real trouble with the Courts’ recent pronouncements must lie elsewhere

– perhaps in its shifting attitude toward the separation of church and state (Kennedy v. Bremerton School District), toward precedent (Dobbs), and toward interpretive consistency (Bruen).

These are all significant complaints to be sure, and each warrants careful consideration. But rather than taking up these criticisms in isolation, I’d like to point to an overarching picture that paints these seemingly disparate complaints as a constellation of related concerns. The public’s historic lack of trust in the Supreme Court may indicate, as Ronald Dworkin once suggested, that “Integrity is our Neptune” – a celestial body we discover only by first recognizing that it’s missing.

So, what is integrity? Simply put, integrity demands that the law be created and adjudicated in a consistent way. Dworkin insists that proper legal interpretation requires commitment to moral coherence. We should strive to comprehend our legislative and judicial history as one of continuity. Judging, Dworkin claims, is not unlike being a writer of a chain novel. You’re tasked with interpreting the major, minor, and latent themes running through the narrative to date and contributing to that tale in a way that does honor to what’s come before – you situate decisions so as to present our legal history in the best possible light.

Ultimately, integrity represents a compromise between the weightlessness of a living constitution and tyrannical rule of a dead hand from a bygone era.

Both of these can devolve into judicial activism and thus commit the gravest of grave sins: legislating from the bench – either by a complete reimagining of the Constitution and our legal history, or by an outright refusal to appreciate the needs of our evolving and ongoing story.

What makes integrity important? The Supreme Court’s legitimacy relies on appearances. We expect justices to rule according to the law and not their politics. The trouble is that it’s extremely difficult to disentangle the two. Do one’s legal convictions shape their political leanings, or does one’s politics dictate their judicial positions? Demonstrating that fidelity to law comes before party loyalty requires a kind of sacred devotion to impartiality and detached public justification (or perhaps simply a renewed commitment to better covering one’s tracks). For if judicial review – the power of unelected judges to strike down the popular will – is exposed as nothing more than partisan warfare by other means, then the game is lost and the lie of democratic representation is exposed. The emperor has no clothes.

How do we know when the clothes (integrity) aren’t there? Dworkin offers a thought experiment: Imagine a law that made abortion criminal for women born in even years but permissible for those born in odd ones. Such a policy might accommodate the 60/40 split in public opinion on the issue.

Allowing each of two groups to choose some part of the law of abortion, in proportion to their numbers, is fairer (in our sense) than the winner-take-all scheme our instincts prefer, which denies many people any influence at all over an issue they think desperately important.

Still, Dworkin thinks, there’s something that rubs us the wrong way about such a compromise. We seem to reject the Solomonic solution of simply cutting down the middle and giving both sides a little of what they want. So what explains our discomfort? Why is this kind of “fairness” not enough? Why do we turn our nose up at “checkerboard solutions” like this one?

Certainly, the decision to kick the abortion question to the state legislatures looks an awful lot like a checkerboard solution – and one that sits uncomfortably with both sides.

It’s hard to see how that ruling fits within our judicial history that treats similar rights (similar to either the right to reproductive autonomy or the rights of the fetus) as national concerns. Such a ruling appears a significant break with traditional practice.

Just last week, Benjamin Rossi gestured at several potential futures for the current political compromise neither side finds tolerable. Pro-life advocates motivated by Body Count Reasoning (explained here by Dustin Crummett) are unlikely to be satisfied with half-measures. Meanwhile, pro-choice proponents decry the unequal burdens arbitrarily foisted upon residents of different states concerning a basic good: health. (Jim Harbaugh can encourage his players to encourage their partners to go ahead with an unplanned pregnancy and offer to adopt all those children all he wants, but the fact remains that pregnancy is not without risk and the decision to go forward is not simply about whether one has “the means or the wherewithal.”)

Unfortunately, whichever way the Dobbs fallout eventually resolves is likely irrelevant to the larger problem. Unless and until we begin to conceive of our legislative and judicial history as a shared project of public justification, there will be no restoring public faith. Without courts committed to something like Dworkin’s idea of integrity, even term limits cannot save us.