Not all opinions are socially acceptable. Oftentimes, there is a range of acceptable opinions and opinions outside that range are not given even the slightest consideration. In May of 2020, a Minneapolis police officer, Derek Chauvin murdered an unarmed man named George Floyd through suffocation over the course of eight minutes while several other officers held back the crowds from stopping him. In response, many people have protested, some people have rioted, and a small number of people have looted. Opinions about these actions vary but, in general, we tend to think that nonviolent protests are acceptable while violent riots are not. A few support riots, but almost no one supports looting. However, the morality of looting is not as clear-cut as public opinion might suggest.

“Looting” is distinguished from ordinary theft in a few important ways. First, the word itself has its origin in describing military forces pillaging a conquered area. Thus, looting implies a breakdown of the ordinary social order. Looters, military or otherwise do not much fear prosecution for their actions.

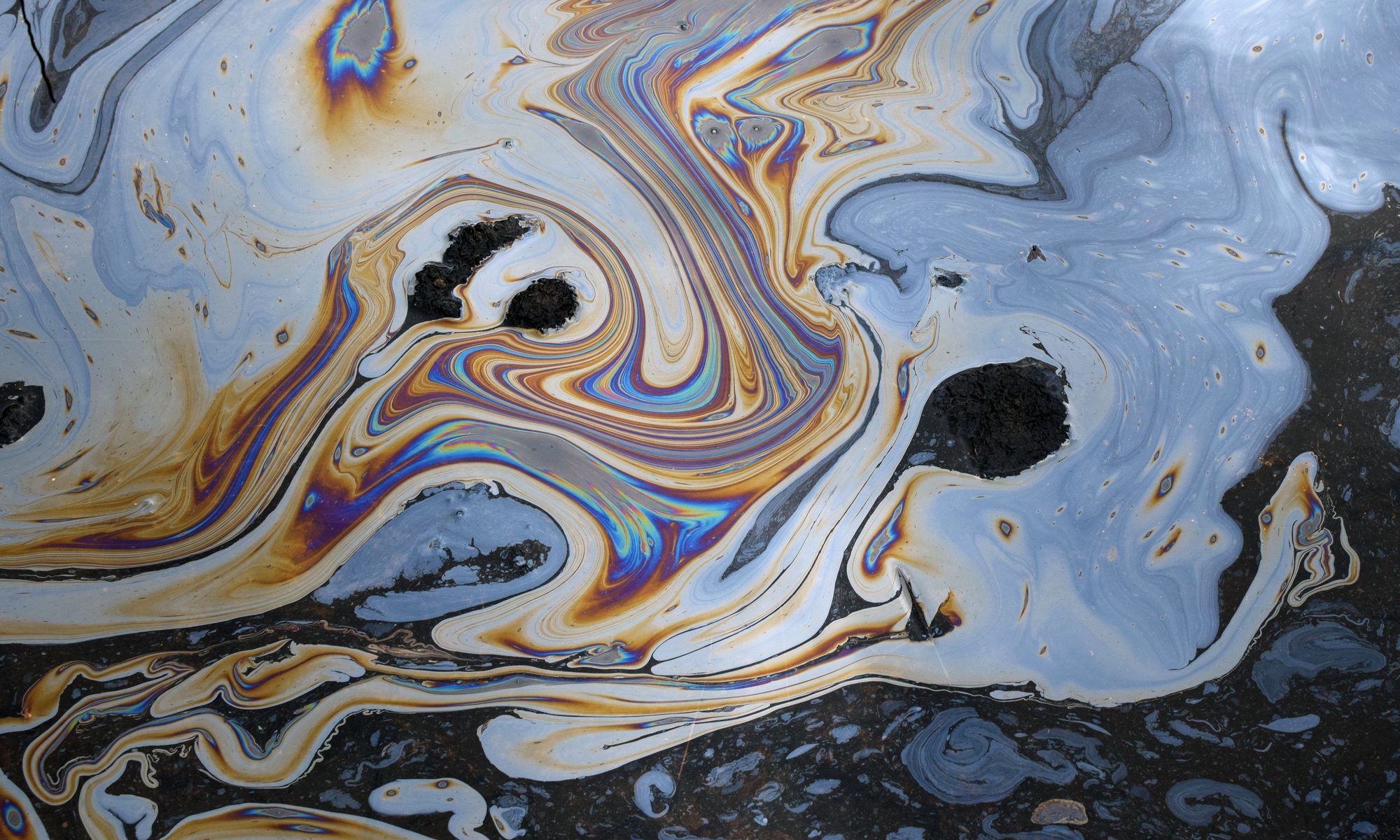

Second, looting is always associated with a context of destruction. Looting involves not only taking property, but also destroying or damaging the business or home where the property is found. As economist Alex Tabarrok argues here, looting may be a worse crime than ordinary theft since “Looters destroy intermediate goods and infrastructure and gain far less than owners lose.”

Third, theft is more or less universally objected to by the members of a community where it takes place while looting can have public support. Thus, looters less frequently hide their identities as compared to thieves. And, looting is often done by groups, pairs, and family units while theft is usually conducted individually. It may be hard to believe that looting would be supported by the community where it takes place, but this instinct toward disbelief can be explained by the flawed assumptions people have about the motivations looters have for their actions.

The conventional view is that looting is universally opportunistic: most people believe that looters see the opportunity presented by the chaos of protests, riots, and the breakdown of law and order and use it to steal things they want for their own gain. A few, more charitable people might say that looters have no ignoble motivation and act according to some instinct that takes over in times of great stress. Almost no one believes that reasonable, well-functioning members of society would engage in violent looting. Nonetheless, these are exactly the sort of people who engage in looting according to the evidence.

L. Quarantelli and Russell R. Dynes were the founders of disaster sociology and wrote on the nature of looting in an article titled “Property Norms and Looting: Their Patterns in Community Crises.” This article was written in 1970 and the authors focused their analysis on the riots and looting that occurred between 1964 and 1968 as part of the Civil Rights Movement. Given the cause of the present riots, this article’s subject, though long past, is analogous enough to the present situation for its findings to stand the test of time.

In contrast to popular belief, they found that those engaged in rioting and looting were not the most disaffected, alienated people. In cases where black people rioted in their communities, up to one fifth of the black population participated, including many employed people with strong social ties. These people did not loot out of economic need and they were not the sort of people one would expect to be overtaken by impulse. In fact, consistent majorities in these communities viewed the riots and looting as a form of protest.

Suffice to say, rioting and looting are not broadly believed to be legitimate forms of protest. People have numerous arguments against these extreme forms of protest. Let’s briefly consider a few of these, one utilitarian, one deontological, one based in virtue ethics, and one based on an appeal to law and order.

People oppose rioting and looting on utilitarian grounds because they believe that these forms of protest cause great harms in the form of destruction of property and loss of life and have no outweighing benefits. This view is especially obvious if you view all rioting and looting as opportunistic, as violence and theft perpetrated by people who want to steal and who enjoy the chaos. However, the foundation of the argument grows shaky if violent protests are capable of affecting large scale social change.

The deontological argument against rioting and looting stems from a belief that in participating in these actions, people fail to uphold their duty to maintain other people’s rights. If people are killed in a riot, those people’s right to life has been violated. Looting violates business owners’ property rights. This argument is only defeated if by rioting and looting people obey some higher duty that they could not obey without violating other people’s rights.

The argument from virtue ethics says that good people don’t riot and loot. People advancing this argument point to preferable protests: the nonviolent protestors today as well as the gold standard, MLK Jr. and those who protested alongside him. These people, like the utilitarians, depend on the idea that looters are inspired to action by selfishness. If rioting and looting serve some higher virtue, then the argument is defeated.

Finally, and perhaps most commonly, people merely appeal to a vague sense that it is wrong to disrupt the social order. These people are opposed to all forms of illegal protest. Even if they claim to agree to the righteousness of the cause of protest, they disagree with the means of protest. The weakness of this appeal is in the righteousness of the social order. It is hard to defend upholding a social order that is deeply unjust; this is, of course, the same argument that MLK Jr. came up against in pursuing his nonviolent, though frequently illegal, protests.

The arguments against rioting and looting might seem overwhelming, but they are not undefeatable. Each depends on some assumptions that are not obviously true. Furthermore, there are some positive arguments that rioting and looting are forgivable, arguments that they are justified, and arguments that they are necessary. By considering these, we may come to a more balanced assessment of the morality of extreme protests.

The easiest argument to make is that looting is, in many cases, forgivable. In making this argument, we don’t have to defend the morality of looting. It is still an important argument to make, though, since many people are advocating extreme violence toward those who are participating in extreme protest. President Trump tweeted that “when the looting starts, the shooting starts,” mirroring former Miami police Chief Walter Headley who used the phrase in 1967. Headley was infamous for what he called a war on “young hoodlums, from 15 to 21, who have taken advantage of the civil rights campaign. … We don’t mind being accused of police brutality.” Obviously, “hoodlum” here is a dog-whistle for young black people. And, it should be obvious that using lethal force against people who are looting, essentially committing property crimes, is disproportional and unconstitutional, equivalent to executing people without trial for crimes that are never punished with execution.

Looting and rioting may be forgivable if they are prompted by incredible rage at a criminal injustice, such as the murder of George Floyd. Though many regard this rage as being misdirected when it is applied to businesses. We tend to think that a person’s judgment being clouded by emotion is enough to diminish their legal culpability. So-called “crimes of passion” are already punished less severely than premeditated crimes. We can extend this reasoning to think rioters deserve a great deal of forgiveness.

MLK Jr. gave a speech called “The Other America” where he said that “a riot is the language of the unheard.” Rather than being an action taken out of selfishness, rioting and looting are actions taken as a cry for help, a call for reform, albeit an extremely disorganized sort of call. He went on to ask this sharp rhetorical question: “what is it that America has failed to hear?” And he answered it thus: “It has failed to hear that the plight of the Negro poor has worsened over the last few years. It has failed to hear that the promises of freedom and justice have not been met.” Given the stunning amount of racist police violence that persists to today, it’s clear his words ring just as true in 2020 as they did in 1967. So, if any crimes at all should be forgiven, looting that causes no physical harm to anyone is one of them. We can still hold that looting is a crime, and that it deserves punishment while still maintaining that it is not unforgivable and deserving of execution by cop or soldier.

Arguing that looting and rioting are justified is quite a bit harder, though still very possible. Prominently, The Daily Show host, Trevor Noah, did this very thing in a video he posted in the midst of the protests. Noah justifies the ongoing extreme protests by appealing to social contract theory and turning the question on its ahead. Instead of asking “why do people loot?” he asks “why don’t people loot?” and attempts to give an answer. Hearkening back to seventeenth century English philosopher Thomas Hobbes, he argues that people are only obliged to follow the laws because they have agreed to do so in order to enjoy the benefits of an ordered, just society that cannot exist without laws. But, as Vanity Fair transcribes him saying,

“As with most contracts, the contract is only as strong as the people who are abiding by it. If you think of being a black person in America who is living in Minneapolis or Minnesota or any place where you’re not having a good time, ask yourself this question when you watch those people: what vested interest do they have in maintaining the contract? Why don’t we all loot?”

The greatest benefit people gain from escaping the Hobbesian “state of nature” is protection of their lives and property. As black people are under constant threat of murder by the government (through the police) they cease to have any reason to obey the social contract. It’s all risk, no reward, essentially. Given that, if they can’t escape the risk, they might as well enjoy the reward of the state of nature, getting to take whatever you can by your own power.

More radically, some argue that looting is justified not because it is itself a right action, but because its rightness or wrongness pales in comparison to the institutionalized looting of the poor by the rich. Former senior adviser of the 2020 Bernie Sanders campaign David Sirota asks why “Working-class people pilfering convenience-store goods is deemed ‘looting,’” while “rich folk and corporations stealing billions of dollars during their class war is considered good and necessary ‘public policy.’” He compares the amount of value transferred unjustly from business owners to working-class people via looting (small) with the amount of value transferred unjustly from working-class people to business owners via the regressive tax cuts of the Trump administration (very large). Perhaps it is wrong to loot, but business owners still end up better off than those who loot their businesses via their “theft” of working-class wealth. Just because that latter wealth transfer occurs through official channels does not make it moral just as the former wealth transfer is not immoral merely because it is illegal.

Some even go so far as to say that rioting and looting are necessary for real social change to occur. Rather than appealing to the moral sensibilities of those in power, these people take a the political realist approach and seek to make the cost of reform less to these people than the cost of continuing the status quo. Self-interestedly, then, the powers that be will influence the political agenda to induce reform. Arguably, rioting and looting works to this end: looking again at the article from E. L. Quarantelli and Russell R. Dynes, we can see extreme protests raged after the assassination of MLK Jr. and less than a week later, major civil rights legislation was passed. Afterward, the frequency of large scale rioting and looting drastically decreased.

On the other hand, rioting and looting can backfire: the powers that be can stop the rioting and looting by enacting reform, but they can also stop it by increasing police repression of protestors and minorities. After the Civil Rights Movement and all the extreme protests that came along with it, there was backlash with the election of Richard Nixon who campaigned on “law and order,” whose administration oversaw the Kent State shooting of thirteen unarmed protestors, killing four, and whose domestic policy chief John Ehrlichman was quoted as saying “The Nixon campaign in 1968, and the Nixon White House after that, had two enemies: the antiwar left and black people.” This idea is commonly known as “the activist’s dilemma.” The evidence suggests that extreme protest actions can enact social change and diminish public support for a protest’s cause. It is paradoxical, but makes some sense if one thinks of change as being enacted by those in power, whose interests are not identical to the population at large.

Looting and rioting are extreme responses to extreme injustices. The murder of George Floyd is an unacceptable symptom of a policing system that is based on “domination” rather than the consent of the governed. It is unjust that more black people are killed than white people than would be expected given the share of each in the population. More importantly, though, it is unjust that unarmed people are being killed by police in broad daylight without trial. Something needs to be done to rectify these injustices. Ideally, change could be instituted by peacefully persuading people but given how these injustices have persisted despite decades of peaceful persuasion, there is reason to question whether more extreme protest measures are justified. At the very least, those who choose to engage in extreme protests such as by rioting and looting are forgivable. There is good reason to think that extreme protests are even justified. And, it may even be that looting and rioting are necessary for real social change. The activist’s dilemma, however, gives us reason for pause.

Ultimately, protest is a chaotic activity by nature, prompted by the rage that stems from injustice. Rather than focusing our ire on those who react imperfectly to those injustices, we ought to focus on the circumstances that prompt people to act in ways that may make things worse rather than better. No matter how many TVs are stolen, no matter how many windows are broken, it is hard to compare these property losses to the loss of human life that comes from the unjust and racist oppression of the people by the government in a country that prides itself on originating such ideas as “liberty and justice for all.”