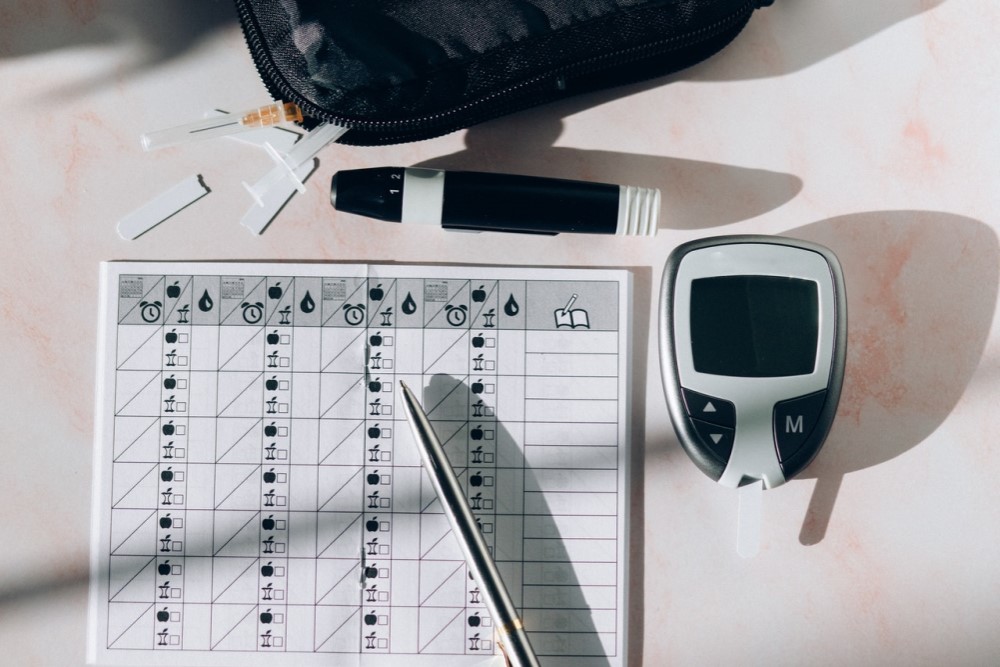

On March 31st the Affordable Insulin Now Act was passed by the House and is now being considered by the Senate. The House bill only applies to people who already have insurance, and caps the out-of-pocket costs for insulin to 35 dollars per-month. It does not address the uninsured, nor does it directly address the retail price of the drug. For advocates, it stands as a limited but hopefully effective response to the surging cost of life-saving insulin in the U.S., the crucial medicine for the management of diabetes.

Sponsoring congresswoman Angie Craig (D) of Minnesota stated:

Certainly our work to lower drug costs and expand access to healthcare across this nation is not done, but this is a major step forward in the right direction and a chance to make good on our promises to the American people.

It is also true to the original promise of insulin.

Isolated in 1921, the firsts patents for insulin were sold to the University of Toronto for the price of one dollar as part of a defensive maneuver to ensure insulin could be produced widely and affordably. Nonetheless, insulin became a goldmine. Cheap to manufacture and widely used, it could bring home a tidy profit even at low prices. Since the early days, three pharmaceutical companies, American Eli Lilly, French Sanofi, and Danish Novo Nordisk, have produced the vast majority of global insulin and captured almost the entire U.S. market. Low production costs continue, but insulin is no longer sold at low prices. At least not in the U.S. Eli Lilly’s popular Humalog insulin is sold to wholesalers at 274.70 per vial, compared to 21 dollars when first introduced in 1996. Further costs accrue as insulin makes its way through the thicket of wholesalers, pharmacy benefits managers, and pharmacies before reaching customers.

One question that emerges from the whole mess is: Who is to blame for this development? Here, blame needs to be understood in two senses. The first concerns all those actors who are partly causally responsible such that if they had behaved differently, the price of insulin would not be so high. American healthcare economics is ludicrously complex, and a discussion of the price of insulin quickly blossoms into biologics and biosimilars, generics, pricing power, patents, insurance, the FDA, pharmaceutical benefit managers, and prescription practices. What idiosyncrasies of the American healthcare systems allow a drug price to increase 1000% without being undercut by competition or stopped by the government? Insulin is not the only example.

But there is a second sense of blame, and that is which actors most directly chose to increase the costs of a life-saving medicine and thus are potentially deserving of moral opprobrium.

The big three manufacturers, with their overwhelming market share and aggressive pricing strategies, are clear targets. However, when investigated by the Senate in 2019, they pointed fingers at pharmacy benefit managers. These companies serve as intermediaries between manufacturers and health insurance companies. Like insulin manufacturers, the pharmacy benefit manager market is highly consolidated, with only three major players: CVS Caremark, Express Scripts, OptumRX. They can benefit directly from higher manufacturer prices by raking in fees or rebates. While noting that only Eli Lilly and CVS Caremark fully responded to requests for documents, the Senate investigation found problematic tactics on the part of both pharmacy benefit managers and manufacturers, such as leveraging market power and raising prices in lockstep.

The bill, it should be noted, is most directly targeted at insurance companies, rather than these other actors. This leads to both an economic and an ethical objection. The economic objection is that by forcing insurance companies to cap prices and absorb the cost of insulin, the insurance companies may simply turn around and raise premiums to recoup profit. The ethical objection is that it is unfair for the government to intercede and force costs of say, aggressive pricing by the manufacturer, onto some other party. The caveat to the ethical objection is that each of the three major pharmaceutical benefits managers have merged with major insurance companies.

What are the business ethics of this all? One approach would be stakeholder theory, which holds that corporate responsibility needs to balance the interests of multiple stakeholders including employees, shareholders, and customers. Pricing a medically-necessary drug out of the range of some customers would presumably be a non-starter from a stakeholder perspective, or at least extremely contentious.

The more permissive approach would be the Friedman doctrine. Developed by the economist Milton Friedman, it argues that the only ethical responsibility of companies is to act in the interest of their shareholders within the rules of the game. This is, unsurprisingly, controversial. Friedman took it as all but axiomatic that the shareholder’s interest is to make as much money as possible as quickly as possible, but the choice is rarely put bluntly: “Would you, as a shareholder, be okay with slighter lower profit margins, if it meant more diabetics would have access to their insulin?” (For Friedman this moral conundrum is not supposed to occur, as his operating assumption is that the best way to achieve collective welfare is through individuals or firms chasing their own interests in the free market.)

Separate from questions of blame and business ethics are the grounds for government intervention in insulin prices. Two approaches stand as most interesting and come at the problem from very different directions. The first is a right to healthcare. Healthcare is what is sometimes referred to as a positive right, which consists of an entitlement to certain resources. There is as yet no formal legal right to healthcare in the United States, but Democratic lawmakers increasingly speak in this framework. Obama contended, “healthcare is not a privilege to the fortunate few, it is a right.” Different ethicists justify the right to healthcare in different ways. For example, Norman Daniels has influentially argued that a right to healthcare serves to preserve meaningful equality of opportunity by shielding us from the caprice of illness. A slightly narrower position would be that the government has a compelling interest in promoting healthcare, even if it does not reach the level of a right.

A completely different ground for intervention would be maintaining fair markets. This gets us to a fascinating split in reactions to insulin prices. Either there is too much free market, or not enough. Advocates of free markets criticize the regulatory landscape that makes it difficult for generic competitors to enter the market, or the use of incremental changes to insulin of contested clinical relevance to maintain drug patents in a practice called “evergreening.”

The “free market” is central to the modern American discussion of healthcare, as it allows considerations of healthcare to not be discussed in terms of rights – that everyone deserves a right to healthcare – but in terms of economics. Republican politicians do not argue that people do not deserve healthcare, but rather that programs like Medicare for All are not good ways to provide it.

At the center of this debate, however, is an ambiguity in the term free market. On the one hand, a free market describes an idealized economic system with certain features such as low barriers to entry, voluntary trade, and prices responding in accordance to supply and demand. This is the use of free markets found in introductory textbooks like Gregory Mankiw’s Principles of Macroeconomics. This understanding of a free market is at best a regulative ideal, in that we can aim at it but we can never actually achieve it and all actual markets will depart from the theoretical free market to some degree or another.

On the other hand, the free market is used to refer to a market free from regulations and interference, especially government regulations, although this understanding does not follow from the theoretical conceptualization of the free market. Oftentimes government interference – such as breaking up an oligopoly – is precisely what is needed to move an actual market towards a theoretical free market. Even for advocates of free market economics, interventions and regulations should be evaluated based on their effect, not based on their status as interventions. From this perspective, the current insulin price represents not an ethical failure but a market failure and justifies intervention on those grounds.

The current bill, however, does not try to correct the market, but instead represents a more direct attempt to secure insulin prices (for people with insurance). This is an encouraging development for those who believe essential goods like insulin should not be subject to the whims of the market. More discouragingly, the bill is likely dead in the Senate.